Olympic Boycotts: Counterproductive or Moral Necessity?

In just under 11 months, the 24th edition of the Winter Olympics is set to kick off in Beijing. While the Olympics are meant to unite the international community through sport, the Beijing Olympics appear to be accentuating divisions. Increased tensions with Western countries and recent revelations about the persecution of China’s Uyghur population have polarized opinions about Beijing hosting the world’s foremost sporting event. Within Western countries, including Canada, calls to either boycott or relocate the Olympics outside of China are growing. This is not a novel idea; there is a long history of sporting boycotts occurring over similar political or humanitarian concerns, most notably during the Cold War. However, with renewed calls for boycotts, it is important to look at why they are used and whether or not they are effective tools for change.

Boycotting a prominent sporting event is a unique foreign policy tool that is employed by states to express a range of humanitarian and political concerns. However, boycotts have been used sparingly in recent years. There has not been a mass Olympic boycott movement since the height of the Cold War, when the 1980 Moscow and 1984 Los Angeles Olympics were boycotted by the American and Soviet blocs, respectively. The Moscow boycott was used as a bargaining chip by President Carter to convince the USSR to withdraw soldiers from Afghanistan. The move ultimately had little effect, with Soviet forces remaining in Afghanistan until 1989. Instead, it inflamed tensions between both blocs.

Recently, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has sought to depoliticize conversations surrounding the Olympics. In an op-ed published by the Guardian, IOC Chairman Thomas Bach wrote that “the Olympic Games are not about politics…Neither awarding the Games, nor participating, are a political judgment regarding the host country.” The intentionally non-political nature of the Olympics is even enshrined in the Olympic Charter, which states that “no kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” Recent failed efforts by non-governmental groups to boycott the 2014 Sochi Olympics in light of a Russian crackdown on LGBTQ+ rights demonstrate the contemporary unpopularity of boycotts. However, there has been a sea-change among Western countries, especially Canada, regarding the politicization of the 2022 Beijing Olympics. A recent poll showed that, amid rising Sino-Canadian tensions, 56 per cent of Canadians would support a boycott of the games. After years of non-politicization, what makes the 2022 Beijing Olympics different?

A series of developments over the past decade has significantly heightened tensions between China and Canada, to the point that many feel that there is an imperative to boycott the Olympics. Canada’s continued detainment of Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer, Meng Wanzhou, led to the retributive imprisonment of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in China. Most recently, a February 2021 vote saw the Canadian parliament officially recognize China’s treatment of Uyghurs as genocide. This motion also included an amendment calling for the relocation of the 2022 Olympics outside of China. As the world, and Canada specifically, descends into what some pundits are calling a “new Cold War” with China, the Beijing Olympics represent a pivotal moment in the development of Sino-Western and Sino-Canadian relations.

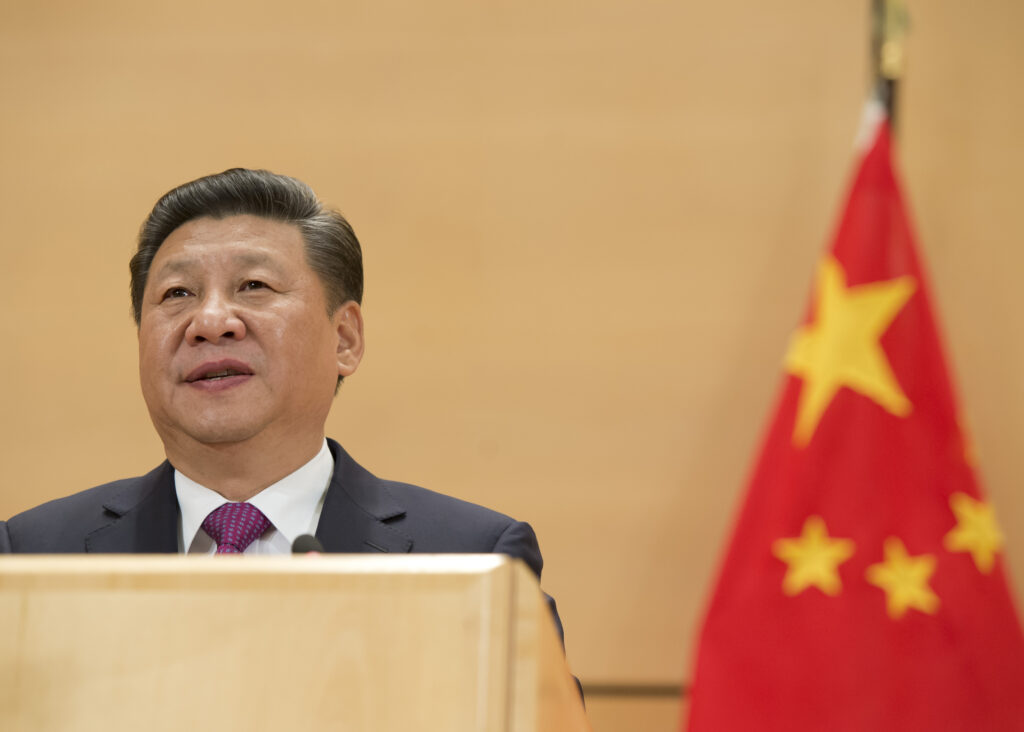

The decision on whether or not to boycott the games will undoubtedly hold political significance. On the one hand, a boycott could be one of Canada’s most powerful political tools against China. While Canada’s relatively small economy limits the impact of any retributive sanctions or political action against China, withholding some of the world’s best winter athletes from the Olympics could publicly embarrass the Xi Jinping regime. Moreover, participating in the Olympics could be seen as contributing to China’s international glorification as they continue to commit genocide. To many, the Beijing Olympics are an example of “sportswashing,” a tactic in which authoritarian regimes use major sporting events to divert attention from their human rights abuses. There are already comparisons being drawn between Beijing 2022 and the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, which glorified Hitler’s Nazi regime shortly before the Holocaust and the Second World War. It is difficult to morally justify participating in an Olympics hosted by a genocide-committing country, and the 2022 games represent a unique opportunity for Canada to take a stand against China on the global stage.

Nevertheless, boycotts are rarely the most effective strategy to enact meaningful change or amplify marginalized voices. Boycotts hardly have a substantial impact following the initial humanitarian and moral statement. As mentioned previously, the USSR continued to occupy Afghanistan for nearly a decade after the US’ boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow. Moreover, China’s track record suggests that it may quickly seek retribution for an Olympic boycott, immediately heightening Sino-Western tensions. There are therefore many opponents to any discussion of a boycott. These actors insist on the fruitlessness of boycotts and believe that the Olympics can be a springboard for positive change. In a strongly-worded press release, the Canadian Olympic Committee wrote that the boycott movement “amounts to little more than a convenient and politically inexpensive alternative to real and meaningful diplomacy. Boycotts don’t work. They punish only the athletes prevented from going.” Instead, they proposed that “we can amplify voices and use people-to-people connections to effect change” by participating in the Olympics.

There is clearly no simple answer to the question of whether the 2022 Olympics should be boycotted. It is difficult to justify participating in the event that sportwashes human rights abuses, but boycotts appear to be an imperfect solution. Instead, the discussion surrounding the 2022 Olympics presents an opportunity for the international community to unite through sport and condemn China’s heavy-handed authoritarianism and genocidal actions. Nelson Mandela once said that “sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, it has the power to unite people in a way little else does.” Sports clearly have the ability to foster unity among a diverse range of countries and peoples in the face of tyranny. Regardless of whether the 2022 Beijing Olympics are boycotted, moved, or neither, it is important to capitalize on this opportunity.

Featured Image: “Olympic Rings Vancouver” by adrian8_8 is licensed under CC BY-2.0

Edited by Matthias Hoenisch