On Debt and Diplomacy: Passing the Microphone on Climate

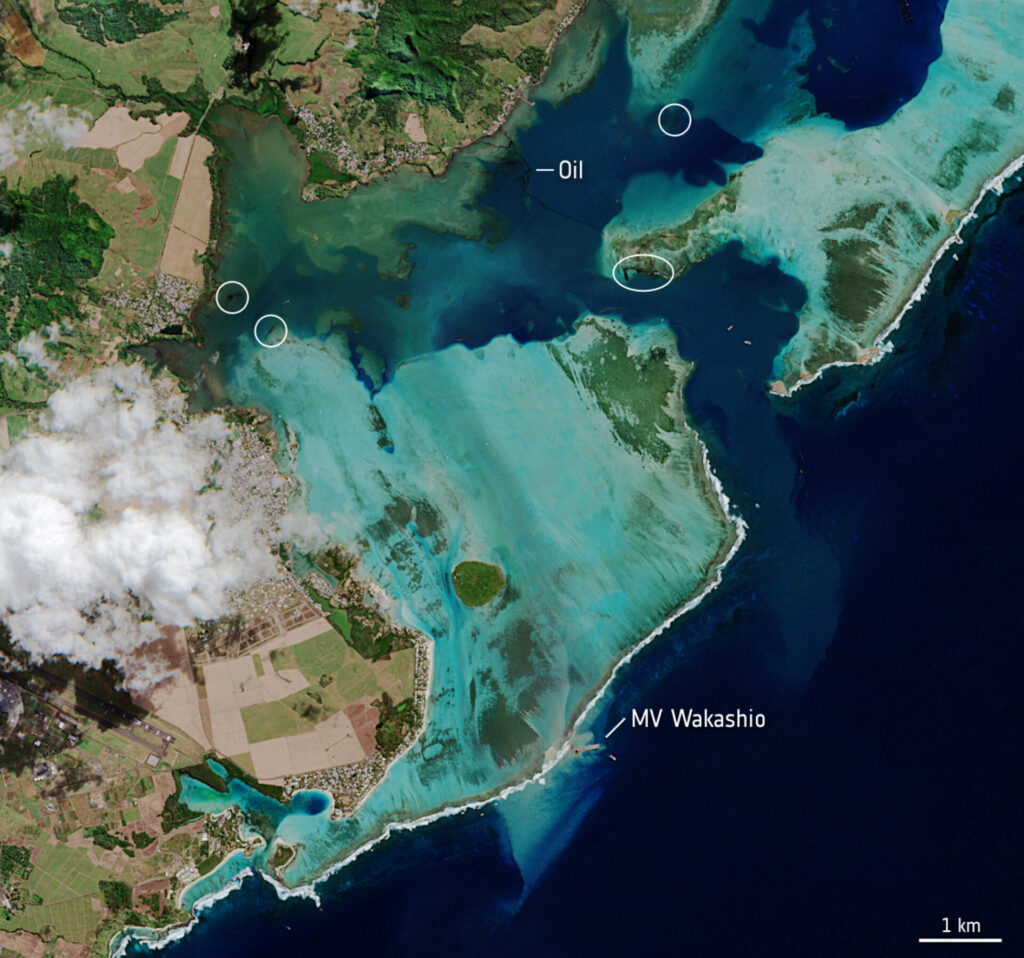

When a Japanese-owned ship began leaking oil into the Pointe d’Esny Wetland off the coast of Mauritius, threatening protected reefs and endangered species, members of local communities, environmental protection groups, and activists raced to commence cleanup efforts. On Aug 7, 2020, the government of Mauritius officially declared the situation an environmental emergency. The source of the leak was the MV Wakashio, which ran aground on a coral reef off the coast of the island nation on July 25. The ship, owned by the Nagashiki Shipping Company and operated by Mitsui OSK Lines, carried 4,000 tons of fuel oil. While the full economic, ecological, and cultural cost of the leak is yet to be seen, it is without a doubt going to lead to setbacks that Mauritius and its citizens may never fully recover from.

The grounding and subsequent oil spill occurred in a stretch of the Indian Ocean known under international maritime law as an “innocent passage.” Zones of innocent passage were legally sanctioned by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to be areas where ships can traverse another state’s territorial waters as long as they do not plan to dock. However, in recent years, the laws of innocent passage, along with several other provisions of the UNCLOS, have drawn criticism from environmentalists for permitting travel through ecologically fragile areas without the consent of local governments. These concerns have yet to be taken seriously as the MV Wakashio was one of three other ships to run aground in Mauritius’ waters in the past five years. The disregard for environmental concerns comes as no surprise as international laws have historically stifled local communities’ voices in favour of international industries profitable to larger powers.

The disconnect between wealthy industries and developing nations in international law has made its way to the global conversation on climate change. Take for example the European Union’s recently proposed carbon border tax, which would tax imported goods based on the amount of carbon emissions resulting from their production. While not explicitly stated, the cost of such a tax would fall on countries, many in the Global South, dependent on revenue obtained from exporting to Europe. Even such progressive policy proposals place a disproportionate amount of the burden of climate change mitigation efforts on developing countries lacking the infrastructure and funds to adequately address what the policies demand. In doing so, proposed climate solutions like carbon border taxes, and even at times the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, strip developing nations of their agency in making their own decisions on climate solutions and sustainability. Such agency has consistently been afforded to wealthy nations without question.

This disparity reinforces the roles of states established under colonial rule wherein wealth gained at the Global South’s expense was funnelled to colonial powers. Even after independence, formal colonial powers continued to take advantage of countries whose economies were initially set with the benefits of extractive industries like mining or oil. As the structure of the global economy was established under these periods of oppression and injustice, it continues to be advantageous for rich countries and debilitating for resource-rich but economically emerging countries. International conversations on climate change have a tendency to ignore these structural imbalances in a way that perpetuates long-standing global inequalities.

To combat the way global climate policy has upheld historical harms of colonialism, the governments of Latin American countries like Bolivia and Ecuador, along with several other countries in the Global South, have submitted requests that the UN integrate the principles of climate debt into global conversations about climate change solutions. As articulated by Ecuador’s leading grassroots environmental organization, Acción Ecología, climate debt is the result of past and continued “resource plundering, environmental damages, and the free occupation of environmental space to deposit wastes, such as greenhouse gases” by developed countries. In a recent proposal to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the government of Bolivia asked that developed countries “commit to deep emission reductions that are consistent with the ultimate objective of the Convention, reflect their historical responsibility for the causes of climate change, and respect the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities in accordance with the UNFCCC” as a means of beginning to compensate for this accumulated climate debt.

Countries pushing for international acknowledgment of climate debt are not asking for financial compensation, despite implications that come with the term “debt.” In fact, in their statement to the UN, the Bolivian government pointed out that it would be “impossible to compensate completely because the atrocities committed by humanity have been too terrible.” Instead, countries like Bolivia are calling for a major systemic shift in the way global climate decisions are made by taking power away from the private sector and bringing focus to grassroots environmental organizations. Enter: the recently proposed Escazú Agreement. The agreement, properly known as the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation, and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, seeks to expand access to environmental information for citizens of Latin American and Caribbean countries as part of an effort to increase public engagement in climate conversations. The agreement also includes protections for environmental defenders who are increasingly threatened by violence from opposing forces, with rates of violence especially high in Latin America. If the agreement succeeds in securing the ratification of just two additional countries, it would be the first environmental human rights treaty regionally specific to Latin America and the Caribbean and the first in the world to protect environmental activists explicitly.

The story of the MV Wakashio and Mauritius underscores the urgent need for a systemic overhaul of the way international decisions regarding climate regulations are made. Past conventions and agreements have had a tendency to conceptualize the climate crisis as an equalizer. In doing so, these agreements often lead to proposals that ignore the fact that international politics do not exist in a vacuum. The legacies of colonialism have shaped interstate relations in a way that has created a severely imbalanced playing field that marginalizes vulnerable communities. These imbalances show themselves through major ecological disasters, as the countries contributing the least to environmental harm become the most affected. Extractive and pollutant industries with corporations based in wealthy countries are causing irreparable damage to nations that cannot afford the price tag on environmental recovery. Yet, even as repetition makes this imbalance increasingly salient to the international community, organizations like the UN continue to fail to include developing countries in climate conversations and consequently neglect them in their proposals and solutions. If any progress is to be made in avoiding a global climate catastrophe, powerful political actors must pass the microphone to those living at the frontlines of the climate crisis.

Featured image: “IMO helping to mitigate the impacts of MV Wakashio oil spill in Mauritius” by International Maritime Organization is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Edited by Selene Coiffard-D’Amico.