Op-ed: Farewell to Golan

This afternoon, President Trump announced that the United States would be formally recognizing Israel’s claims to the Golan Heights, a mountainous region between Syria and Israel. Currently considered Syrian land under occupation by much of the international community, this White House decision paves the way for the international legitimization of the Israeli occupation of the territory. Should the world follow suit, this will be the first internationally recognized addition to Israel’s territory in decades.

This could easily be another article on how this move speaks to the Trump administration’s growing closeness with Prime Minister Netanyahu. I could also adopt a classical political science approach and discuss how this might alter “the careful balance of power in the Middle East”. One might also mention that the territory is of great strategic value to Israel, providing a buffer between itself and a hostile neighbour. I could also, as so many have, point to the fact that thousands of Israelis now call Golan home.

But to write that article would be to miss out on something fundamental. There is something near-sociopathic in how we study political science and history in our universities. To understand the world, it is demanded by our institutions that we be cynical, sober, and free of any pathos. But there is a human cost to war, and to our political decisions.

My grandparents were born in the Golan Heights, in a city called Al Qunaytirah. My grandfather ran a general store in the village, that allowed him to support my grandmother, mother, and newborn uncle. My grandfather was a charismatic man and used his connections in the Syrian military to gain access to the first television set in the village. A humble and generous shopkeeper, he kept the television set in the shop window, allowing citizens to watch the news publicly. There was a strong community in Al Qunaytirah, and my family often found themselves at the centre of it.

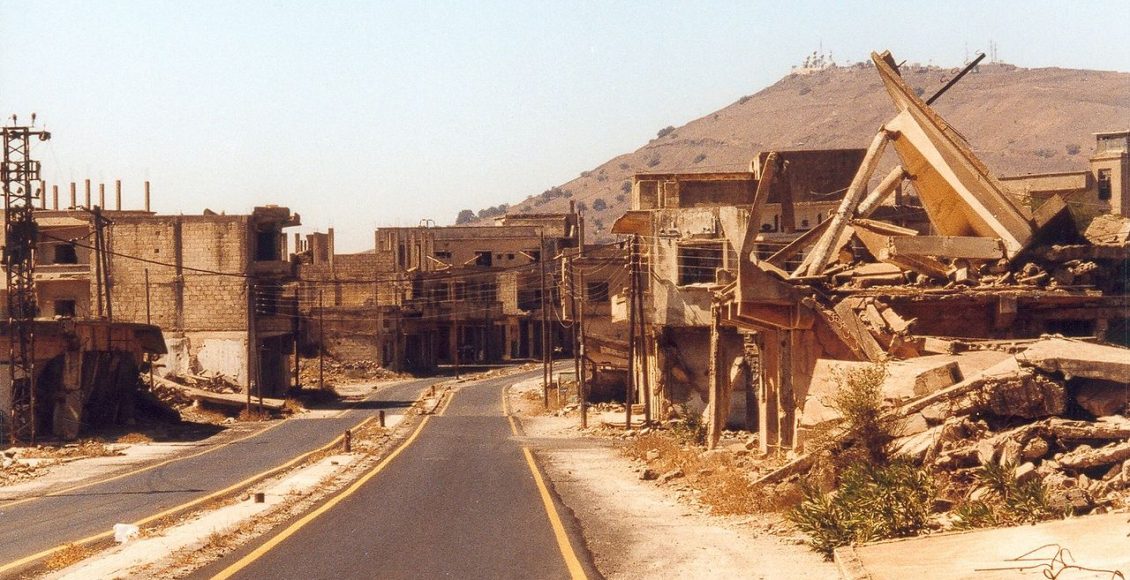

But within 6 days in 1967, it was gone. The city’s hospital was used for target practice. My grandparents’ home, which had stood for decades, was reduced to ash. Bulldozers were brought into to the city square, and levelled and demolished all buildings that stood in their path. Never again would there be a sense of community in Al Qunaytirah. There would be no home for anyone to go back to.

My aunts, uncles, grandparents and my own mother found themselves as refugees in Damascus. Within a couple of years, the whole family would make their way to Montréal, settling in the city’s east end. With time, they would rebuild their community, integrating into the larger Lebanese and Syrian diaspora that called the city their home. Although they were well supported by their adopted community, my family would live in crushing poverty for the next few decades, my grandfather taking on odd jobs to support the family.

We are told in mainstream accounts of the Six Day War that the capture of the Golan Heights was necessary to maintain Israel’s security. Nowhere in these accounts is my family’s story, or the story of thousands of other Syrians, ever mentioned. Nonetheless, we continue to parrot standard-issue political science jargon, using meaningless buzzwords like “security”, “interests” and “stability”.

I could have written that kind of article. But if I were to do that, I would be falling into the same orientalist tropes that rob Arab and Muslim peoples of their agency. I refuse to internalize this dehumanization. I have already lost my language. I refuse to forget my history. We are not geopolitical pawns.

My grandparents hoped to go back to their home before they pass.

“I will take you there one day,” is something my grandfather would always tell me.

I now know they never will.