Op-Ed: Words Matter

An August memorial for the victims of the El Paso mass shooting

An August memorial for the victims of the El Paso mass shooting

In 2015, I could have named you every all-star on the White House’s speechwriting staff. Jon Favreau, Cody Keenan, David Litt, Sarah Hurwitz—I knew them, because I wanted to be them.

Back then I was in Grade 11, hot off a binge-watch of The WestWing and intrigued by the mythology of American government that the show had so beautifully cultivated. Inspired by the shows real civics lessons and its fictional president, I started dreaming about speechwriting myself, quietly carrying the conviction that, perhaps one day, some promising young candidate would absolutely need a Canadian on the communications team and I could be their girl. A bit of a delusion, perhaps, but I didn’t care. Like all of us, I had grown up in the light of the Obama presidency, and those West Wing-esque success stories felt pleasantly possible.

But just as quickly as my fascination with the entire field arose, it abated. Trump got elected, I went off to university, and because everything in the United States and in my own life became so loud, my love for American politics grew quiet. As I moved into a more serious phase of schooling, I had to confront the fact that I was a Canadian with no direct stake in the country (and, therefore, no claim to a spot in an entry-level internship). Plus, those political jobs were pretty poorly remunerated. Plus, I had midterms and finals and papers to do, and no time to waste on the cycle of twitter-scrolls and eye-rolls that characterizes the current White House. I had to get real, and I had to grow up. So, while the country slipped away into Trumpian malaise, I slipped away from the country.

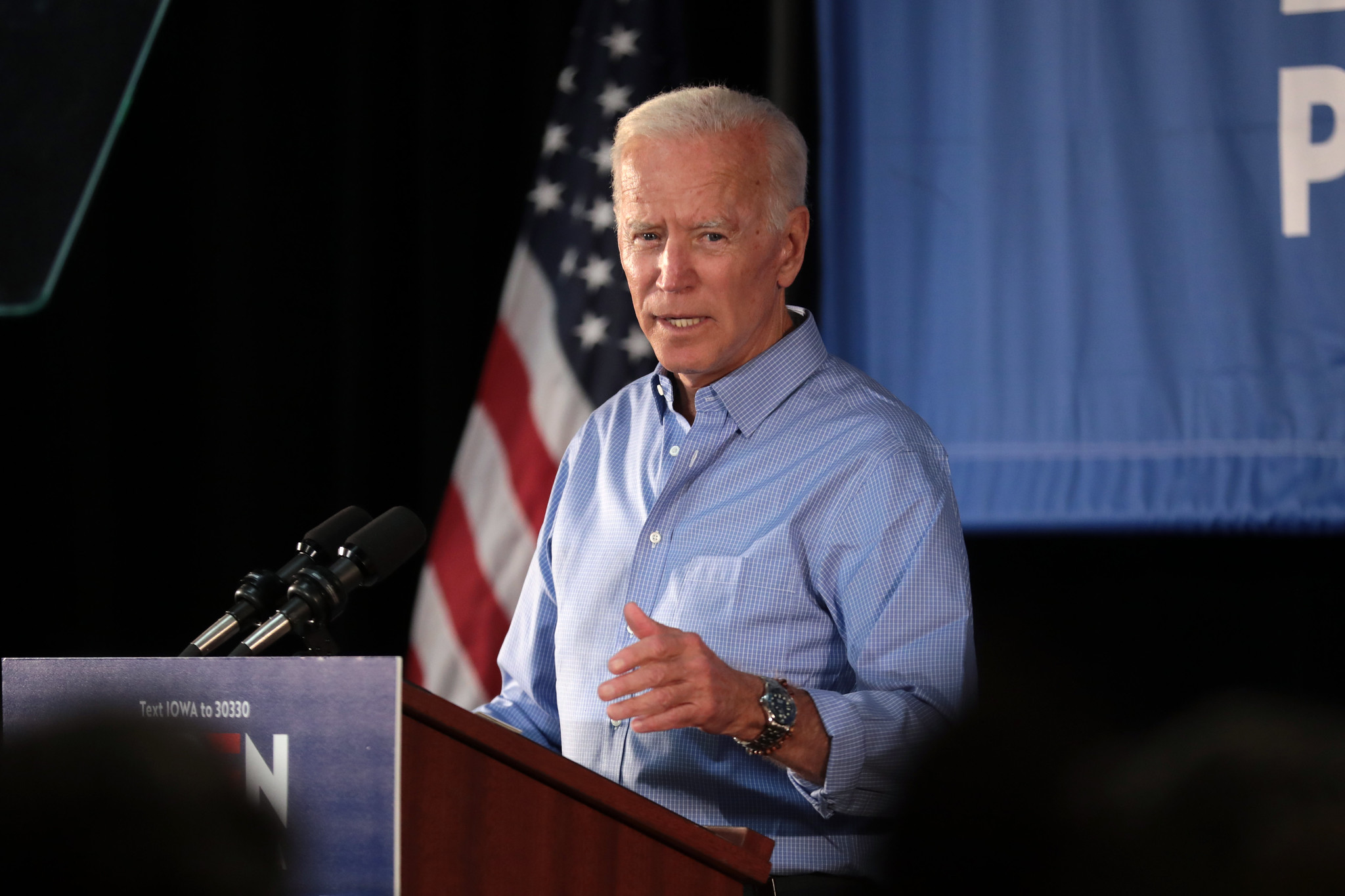

It was only this past summer, when Joe Biden made a speech in Iowa that was supposed to be about agriculture and ended up being about what a president could be, that I felt that flutter of excitement that had drawn me into the American orbit on all those high school nights. As he stood sternly in front of the cameras, he offered audiences that classic presidential cadence that is so utterly absent from Trump’s own repertoire. He blasted the president as a caricature who “shows no moral leadership,” but he also highlighted the American people as a people who could do better—who could “choose hope over fear. Science over fiction. Unity over division. And, yes — truth over lies.”

From its emphases to its quiet moments, to its crescendoes about the American Idea and the need to restore it, the speech possessed a basic beat that made me ready to open a new tab and start googling everyone who wrote it. It felt good to perceive that rhythm again and to care about it, irrespective of whether Biden would be my first pick for the office. It made me echo in my mind what the Vice President had said to the audience that day—that, if anyone else wins in 2020, the Trump presidency could be regarded as an “aberrant moment” in American history, and the old hope would come back, and I could return to my hobby, and we could all move on.

And then I remembered why the content of Biden’s speech had to change in the first place. It was because 22 people died in a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, slain by a man who was shooting at them because of their ethnicity. Undoubtedly, as many commentators and politicians noted at the time, the gunman was picking up where he believed Trump’s own tweets and rallies left off.

Good, old-fashioned rhetoric—a well-crafted speech delivered at the right moment in time—was why I loved American politics so deeply. But where Obama and Biden and so many others seemed to wield the gravitas of their offices in ways that vested their words with hope and beauty, Trump abused it, shooting out insidious word-vomit that only validated hate and ugliness. As the former Vice President bluntly acknowledged in Iowa, “A president’s words matter.” I suppose I used to understand only the positive connotation of that phrase; the potential contained within it for speeches about national healing, or victory, or going to the moon. Two years of idiocy and incitement later, we recognize the terror that words can wreak.

This two-year hiatus I seem to have taken from American politics—from around the time of Trump’s inauguration until this jolt of a speech—has been bookended by acts of pure evil. In November of 2016, it was the anti-semitic words of white nationalist Richard Spencer that drove me to shut the laptop. This summer, it was 22 Americans in a Walmart who were targeted because of the language they spoke and the country they might have come from. In the interim, white supremacy has come for 51 Muslims worshipping at two mosques in Christchurch, 11 Jews praying on the Sabbath in Pittsburgh, and for too many more to name.

It occurred to me that while so many in the world have grown weary of the president’s scramble of stupidity and dogwhistles (myself included), its darkest corners have stayed tuned for the past two and a half years. The average follower of American politics might have been saturated into indifference, but its most insidious elements have only been emboldened. I stopped listening for great speeches I knew would never come, but the people who hate me, as a Jew, or my fellow Canadians and Americans, as other minorities, have hung on every word.

When good people shrug off the kind of repugnance we see from the American president—when we dismiss it as the usual unusualness—we obscure the evil that those words actually unleash. For some, and particularly for those who lean conservative, that obfuscation makes Trump appear sort of palatable, and that makes reelection seem startlingly possible. But, of course, reelection could only spell more vitriol, more shootings, and more fear. So for that reason, Biden’s words were a wake- up call. They reminded me that, more important than nurturing some delicate personal dream about speechwriting, following American politics right now is broadly important because to ignore it is to allow the bigots to win.

It is, therefore, not only about ‘coming together’ with fellow minorities and allies in the face of racism, or indulging in any of the other tropes that flow in the weeks and months following a tragedy. It is more plainly about staying politically informed, even when doing so feels more like a chore and less like the novel adventure it once did. It is about recognizing the fact that, outside the walls of our own government in Ottawa (and sometimes inside it, too), xenophobia and hatred exist, and someone might one day emerge from our woodwork to amplify those bad ideas, if given a mandate by voters who are just holding their noses for better tax policies. It is about drawing a clear line from Trump’s rhetoric to the end of a racist’s AK-47, and proving to the electorate that, indeed, “Words matter.”

As I mentioned, I’m not sure Joe Biden would have my vote for the Democratic nomination, if I even had one to give. But the guy did have a point. He made a great speech about the power of bad speech, and in doing so, he reminded me and probably a few others why we used to love American politics. He also made me realize why ducking out of it—and out of its Canadian counterpart—is dangerous.

Edited by Alec Regino