Opinion | A Love Letter to the Internet

On Monday, January 31, the New York Times bought Wordle, a website that, as of January 31, generates no revenue. Rather, the site has another value entirely: nostalgia.

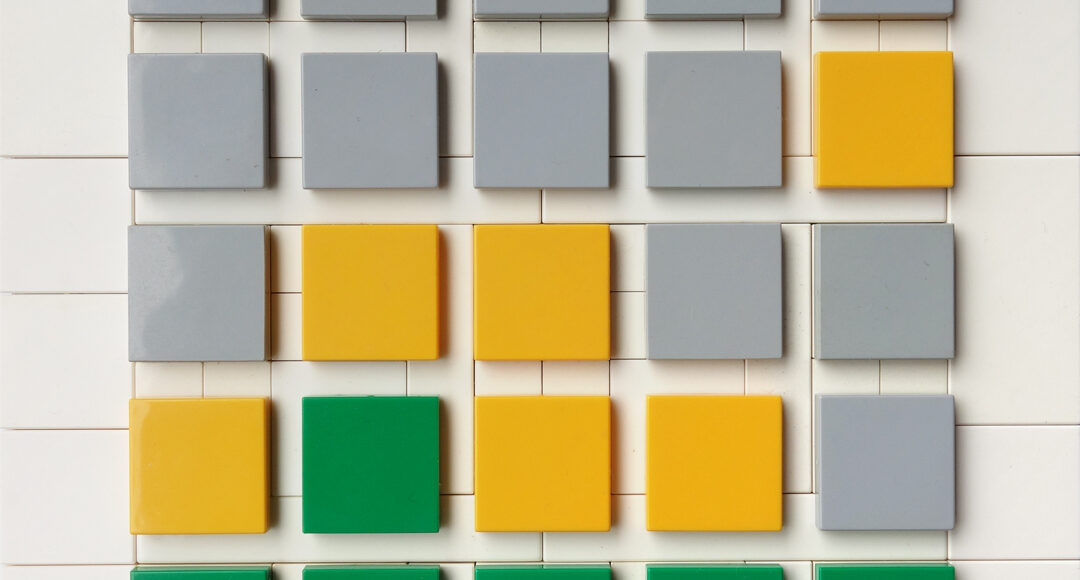

Wordle was created out of love. Josh Wardle invented the game in 2021 for his partner, who likes word games. It’s a simple game: users have six tries to guess a five-letter word, generated once daily, aided by colour-coded hints telling you if you have the right letter and if it’s in the right spot. The site is almost painfully sparse, with the most complicated feature being the option to share your results (in the form of green, yellow, and grey squares). Wardle released Wordle publicly in October, but it did not take off until early 2022 when millions began to play daily. This rapid rise to Internet fame is likely why the Times was so eager to purchase it, lack of monetization notwithstanding.

However, as Wordle is subsumed into the media giant ecosystem, we must remember its roots. Wardle (ironically enough, in an interview with the Times) attributed the game’s success to the fact that it “doesn’t want any more of your time.” It is specifically designed to use only three to five minutes of your day, offering no additional levels or means of stimulation. Furthermore, the site collects the bare minimum of data necessary from you — only cookies that remember your score — and features no advertisements. Because of this, Wordle is not only an anomaly in the Internet’s current age but a relic of a long-forgotten past.

The origins of the Internet are complicated, which was exactly the point. Its original developers were dedicated to the premise that it should have “no global control at the operations level” — in essence, no one person should be able to determine its fate. At its most basic level, the Internet is simply a conglomeration of connections: a collection of computers and communities, all talking over each other all the time.

It was quickly picked up and used by researchers, who identified the potential for unprecedented information-sharing. Much of the first Internet-supporting communications infrastructure was built on the urgings of reports from the American National Research Council in the early 1990s, which described an “information superhighway” that would facilitate a national research network and allow for more data and findings to be shared than ever before. This spirit of increasing access to information guided much of the Internet’s first milestones: for example, one of its first features was Project Gutenberg, developed in 1971 by writer Michael Hart as the first digital library, creating and offering free eBooks on thousands of topics and in dozens of languages. Twenty-seven years later, Google was born and fundamentally shaped how people accessed information for decades. However, the biggest feature of the Internet for over twenty years may have been its incredible ability to facilitate community. 1985 saw the creation of the first online community, WELL (which persists today), while the birth of Wikipedia in 2001 created the first collaborative encyclopedia. Most notable in recent years is the invention and rise of Facebook, a social media platform that was originally meant to connect people who otherwise would have never spoken to each other.

Things shifted in 2012. Facebook went public (the company – the site went public in 2005), performed underwhelmingly in its first few days at the market, and promptly went home and monetized the hell out of itself. Suddenly, Facebook was filling with advertisements in a way it hadn’t before: ads became bigger and more pervasive on the site and were quickly added to Facebook’s newest acquisition, the formerly ad-less Instagram. By September 2012, Facebook learned how to specifically tailor ads to users so that people saw what they were most likely to buy. The company’s total annual revenue increased by 36 per cent.

And thus, the attention economy was born.

On the Internet, information is not scarce, while attention is; companies are therefore interested in your time to build value. Herbert A. Simon, a Nobel Laureate economist, coined the term “attention economy” to argue that “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” This is bad news for websites that rely on advertisements — which only work because users see them — to make money. Websites are therefore designed to be as enticing and addictive as possible, measuring success by how long people stay on them. In a sense, today’s Internet is no longer free: you’re just not the customer. Rather, you’re the product — or more specifically, your time is — to be sold to advertisers.

We recognize that the attention economy is not ideal. We acknowledge our digital addictions and vow to do better by setting app timers and sleeping with our cellphones in the other room. But do we really care about being commodities? The World Economic Forum estimates that by 2025, 463 billion gigabytes of data will be created each day globally — much of which is generated by and about people, suggesting that our online dependencies are not likely to wane. The importance of social media shows no signs of declining, especially as media apps like TikTok and YouTube continue to grow. By all quantitative measures, the attention economy is booming.

But the success of Wordle suggests a different story, wherein Internet users are tired of being pumped full of advertisements. Wherein Internet users forsake infinite content in favour of a small dose of quality entertainment. Wherein Internet users become people again, who just want to play a little game with their friends. It’s reminiscent of the beginnings of the Internet, when we were there to learn, have fun, and connect with each other. Wordle’s popularity suggests that we miss those early days more than we like to believe.

Perhaps the Times will preserve Wordle in its current, universally accessible form, but I wouldn’t hold my breath; nobody buys anything for a million dollars that are not worth over a million dollars. But maybe it will, and preserve the last gasp of a free and open Internet.

I really hope so.

Edited by Matthias Hoenisch.

Featured image LEGO Wordle ⅚ by Conrado is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.