Opinion | Cyclical Poverty and Class Solidarity in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite

Since winning the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, Parasite has been a favourite among critics, audiences, and award judges. Parasite is a unique movie that will make you reflect on a multitude of themes for several days after you’ve watched it. This, now Oscar-winning film, is a satire and thriller based in South Korea that explores wealth inequalities and the lengths we go to survive.

The film centres around two families: one scheming and poor, the other vapid and obscenely rich. The film tells the story of a class war, as the impoverished Kims grift their way into a mansion inhabited by the much wealthier Parks. The story is told from the perspective of the former who get their break when the Kim children, Ki-woo and Ki-jung, start working as tutors for the Park children. Ki-woo and Ki-jung then manipulate the Park family into firing their housekeeper and chauffeur so that their mother and father can take over these positions instead. The film’s main plot twist begins when the Kims celebrate their new positions at the Park’s residence while the Park’s are away on a camping trip. During this scene, Ki-taek, the patriarch of the Kim household, wonders if the previous chauffeur, Yoon, was able to find a new job. Their fate is sealed when Ki-jung—instead of being empathetic towards the former employees—exclaims: “Fucking hell! We’re the ones who need help! Worry about us, okay? Not the driver, but me, please!”.

Bong’s cinematography is famous for condemning capitalism while portraying layers of vulnerability and exploitation. Many of these themes are present in Parasite. Above all, Parasite is a realistic lesson on the importance of class solidarity and on the impact of cyclical poverty. By tricking the Park family into firing their employees for their benefit, the Kims are not only scamming an overly privileged and ignorant family, but effectively harming other poor and working-class people as well. “There is the poor, and the even poorer,” Bong explains. “It’s a story about the powerless fighting each other, and that is the saddest thing.”

The Kims’ plan unravels when Moon-gwang, the former housekeeper, returns to the mansion claiming to have left something behind: her husband, Geun-se, who has been hiding from violent loan sharks in the emergency bunker beneath the house for the past four years. The story then stops being about the poor triumphing over the rich and becomes a battle between the working-class over limited resources. The salaries obtained by Ki-woo and Ki-jung would have probably been enough to support their family; however, their desire to distinguish themselves from other members of their economic class lead them to desire more. While it is common to desire a comfortable life, letting Geun-se hide in the Park’s basement would have had no immediate repercussions for the Kims; had the Kims simply recognised the humanity of the Park’s former staff, they could have avoided the senseless violence that occurs later on in the story. In one of the film’s final scenes, to avenge his wife’s death following a fight that had ensued due to the Kims’ refusal to help, Geun-se cracks Ki-woo’s skull with a rock and stabs Ki-jung to death in the Park’s backyard.

Considering the theme of class solidarity that was previously discussed, one might wonder what the title of the movie suggests. Who or what is the “parasite”? It would make sense for the parasite to represent the working-class who infiltrate the world of the rich. The Kim family knows, through both instinct and bitter experience, how to make themselves acceptable to the wealthy—how to dress, style their hair, talk, walk, move, etc. And yet they’re in danger of being exposed because they have a distinctive and presumably unpleasant smell, which the Park family points out repeatedly throughout the film.

“Not passing the sniff test” is a reference to working-class people trying to move up the ladder and failing. It has long been embedded in capitalist beliefs that there is something inherently inferior about the lower classes that justify the perpetuation of class stratification. In this case, their smell was that thing that, no matter how hard they tried to change, was inherent to their economic status. When trying to take their car keys from under Geun-se, who at that point had been killed by Ki-taek and is lying on the ground, Dong-ik, pinches his nose. The Park family, until that moment, might have appeared “nice”, but they weren’t able to overcome what differentiated them from the Kims, even though it meant letting one of them die. It is the same self-centered and careless attitude that the Parks display that led the Kims to their demise.

The film ends with Ki-woo writing a reply to Ki-taek who was now hiding in the bunker of the Park mansion, after having killed Dong-ik out of rage. As Ki-woo speaks in a voice-over, we see his fantasy take shape. He has a plan: he’s going to go to college, get a job, and make a lot of money so that he can buy the house and his father can safely walk up the stairs and out into the sun. His fantasy ends with a hug between the father and son; however, the film doesn’t end there as the audience is reminded that, previously in the film, Ki-taek had told Ki-woo that plans always fail. The camera reverts back to Ki-woo writing this imagined future to his father. “It’s quite cruel and sad,” explains Bong. “But I thought it was being real and honest with the audience. You know and I know—we all know that this kid isn’t going to be able to buy that house. I just felt that frankness was right for the film, even though it’s sad.”

The reality is that the Kim family will always live in a proverbial underground from the rich. The father becomes the new resident in the bunker, while the Parks move out, only to be replaced by a rich German family. The particularities may have changed, but everyone’s station has remained the same. There will always be another wealthy person to live upstairs, just as there will always be another poor person positioned beneath them. By the film’s conclusion, the Kims are literally and metaphorically fractured, forced to start back at square one with even less than they had when we first met them. And such are the dreadful effects of cyclical poverty.

In an interview with Vulture magazine, Bong explains why he wanted Parasite to end with a “surefire kill”: “Making the audience feel something naked and raw is one of the greatest powers of cinema. […] It’s not about telling you how to change the world […], but rather showing you the terrible, explosive weight of reality. That’s what I believe is the beauty of cinema.” Class solidarity is inherent to the system in which we live. The harsh reality is that we won’t survive or succeed alone, and although it seems hard at times, we should constantly thrive to extend our hand a little further. The portrayal of the importance of class solidarity and of the weight of cyclical poverty is what I believe to be the true the beauty of Parasite.

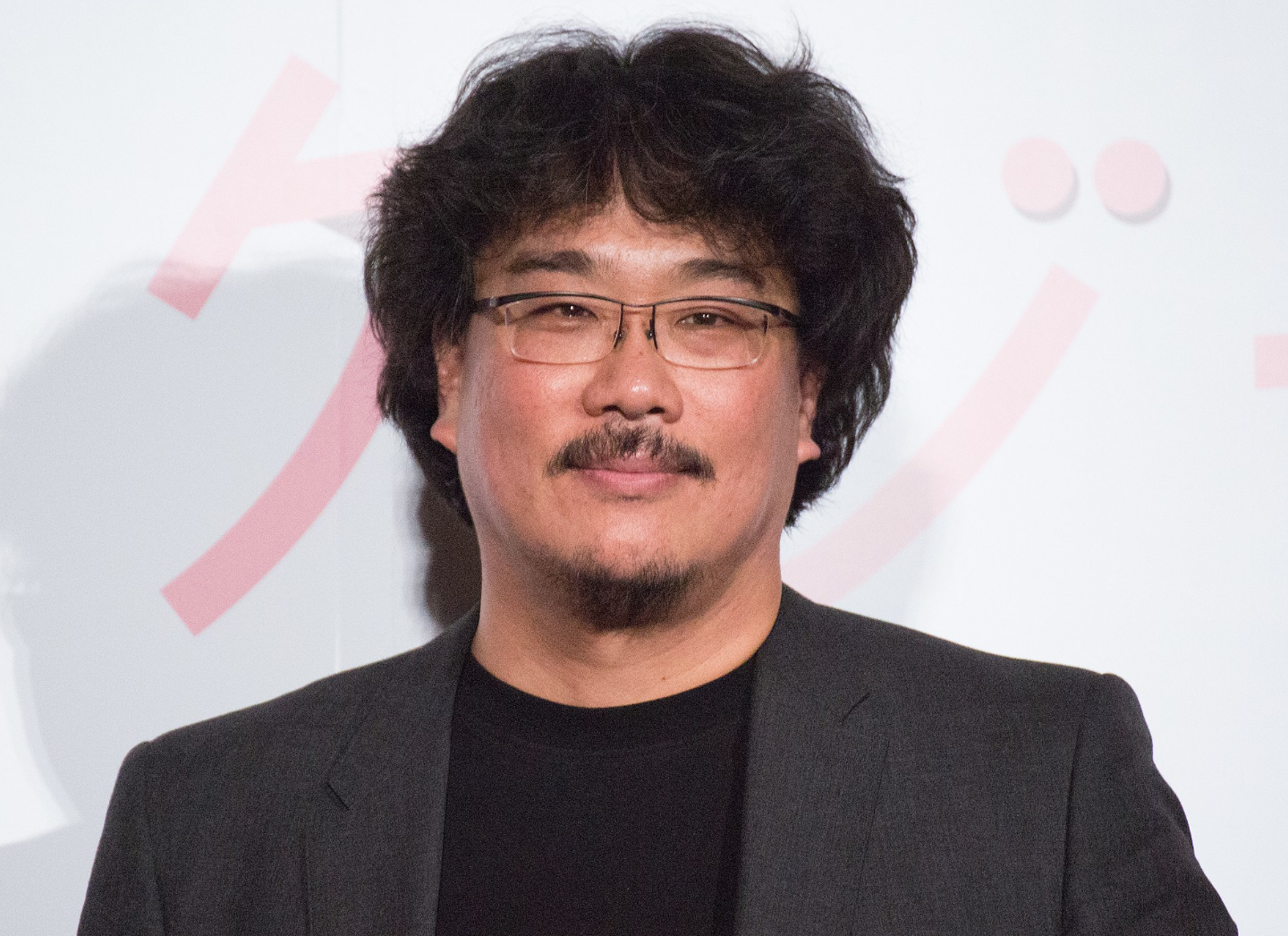

The featured image “Parasite (2019).” by Kinocine is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.