Overcrowding at Rikers: A Tale of Two Americas

"Rikers Island Jail" by Tim Rodenberg is licensed under CC BY 2.0

"Rikers Island Jail" by Tim Rodenberg is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Situated in the East River, overlooking the New York City skyline, is one of the United States’ toughest jails. The Rikers Island jail complex (or Rikers) is infamous for its lawlessness and violence, as well as the extremely harsh living conditions imposed on its inmates. For years now, activists have been calling for its closure because they believe Rikers offers little social rehabilitation. These campaigners view Rikers as hindering and preventing the detained from ever re-entering society in a productive manner. However, the dysfunctionality of Rikers Island Jail is just a reflection of the defectiveness of the American criminal justice system, which is deeply representative of the United States’ deep-seated problem of racial and socioeconomic inequality.

There is an important difference between jails and prisons. Jails confine people awaiting trials or who have been found guilty of minor crimes, while prisons generally house criminals who have been found guilty of major crimes. Most inmates at Rikers are awaiting trials, meaning the justice system presumes them to be innocent until proven otherwise. However, these detainees are treated like second-class citizens within the violent and aging jail complex.

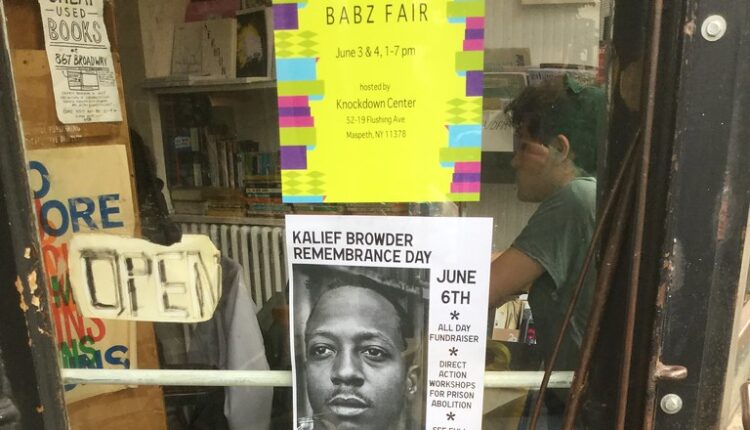

Recently, pictures of Rikers’ inmates in overflowing cells were circulated in the media, demonstrating that the jail was in the middle of an overpopulation crisis. Further reports found that the current instance of overcrowding is being driven by the New York City criminal justice backlog and staffing shortages. This led to New York City officials publishing a report that alleged detainees at Rikers were being detained for more than nine months on average, an 88-day increase compared to pre-pandemic wait times. Such backlogs can have tragic consequences, especially when the jail’s conditions are as dire as at Rikers. One example is the suicide of Kalief Browder, an adolescent accused of stealing a backpack in 2010 who ended up spending three years at Rikers. He exemplifies the consequences that judicial backlogs and socioeconomic inequality can inflict on the lives of Americans, especially Americans of colour.

After Bowder’s initial arrest, his bail was set at three thousand dollars, a price neither he nor his family could afford. As a result, Browder was sent to Rikers. During his time at the jail, Kalief spent nearly two years in solitary confinement, a practice that has devastating effects on those it is used on. Psychological reports agree that this practice, which limits sensory stimulation and social interaction, can cause significant cognitive, behavioural, physiological, and emotional effects. Some commonly reported symptoms include psychosis-related effects, with some inmates recalling experiencing hallucinations, illusions, and paranoia during their confinement. Developing symptoms of depression is also notoriously commonplace. During his time in the jail, Browder was also brutally beaten by correctional officers as well as other jail detainees on multiple occasions. These factors eventually led to his suicide in 2015, only two years after he had been freed from jail.

Browder’s story demonstrates issues not only with Rikers but with the American criminal justice system. The cash bail system that is commonplace in the United States –– and which trapped Browder –– disproportionately affects people of lower income who cannot afford to pay the fees. These people are sent to jail as a result, where they can spend weeks, months, or even years before seeing their day in court.

Due to the chronic backlog of many criminal courts, detainees commonly plead guilty to crimes they did not commit in order to be granted a plea deal and see an earlier release from jail. However, employers are less likely to hire convicted felons, which affects their housing options and even voting rights in certain states. People can find themselves trapped by the American carceral system without even knowing the full consequences of a guilty plea.

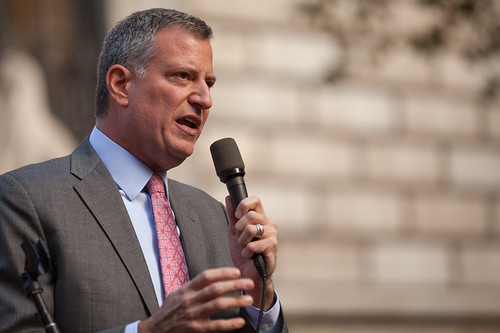

The recent images of detainees sleeping on floors in overcrowded cells have added to the political pressure exerted on New York City and on Mayor Bill de Blasio to shut down the jail. As underlined in new reports, Rikers is expected to be closed by 2026. However, some are already skeptical of this deadline, especially because the proposed solution is to build four new jails. The Mayor has also come under scrutiny for this plan not only because the project appears to be delayed, but also because this would once again mean relying on jails as a solution to social problems that could perhaps be solved in other ways.

As more people gain awareness of the workings of the American carceral system, alternatives to prisons and jails are being examined. What is often emphasized is that the disproportionate representation of poor and Black Americans in jails and prisons can be linked to structural racism within the United States, exemplified in the over-policing of communities of colour and Black Americans. Furthermore, the draconian laws put in place during the ‘War on Drugs’ have effectively criminalized addiction as well as casual drug use, which in many cases separates families and disrupts entire communities. The prison abolition movement offers an alternative approach to crime.

Mariame Kaba, an educator and organizer advocating for prison abolition, explains in her essay entitled “So You’re Thinking of Becoming an Abolitionist” that “crime and harm are not synonymous. All that is criminalized isn’t harmful, and all harm isn’t necessarily criminalized.” In an interview with scholar and activist Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Kaba added, “I am looking to abolish what I consider to be death-making institutions, which are policing, imprisonment, sentencing, and surveillance. And what I want is to basically build up another world that is rooted in collective wellness, safety, and investment in the things that would actually bring those things about.”

Talks of prison obsolescence and abolition are not new. For years, works such as Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Y. Davis have been making ripples. In more recent times, the cause has also been championed by figures such as Darren Mack, a co-founder of the Freedom Agenda, which advocates for better community resources and different solutions to crime and poverty instead of advocating the opening of new jails.

More recently, Black Lives Matter protests have also brought more visibility to the question of prison abolition. Although the popularization of these ideas is encouraging, cases such as Rikers and its replacements are potent reminders of the complexity and difficulty that abolition would require. Jails and prisons are deeply ingrained within the American collective imagination, and finding alternative solutions and deciding where to invest resources sometimes appears like an insurmountable task. However, the work of community organizers who have made it out of the carceral system and fight for a better future every day provides glimpses of hope, thus necessitating closer attention.

Featured Image “Rikers Island Jail” by Tim Rodenberg is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Rory Daly