An Overview of the 2017 Montreal Mayoral Election

Left image source: http://bit.ly/2idzcPC

Right image source: http://bit.ly/2xGWa3x

Left image source: http://bit.ly/2idzcPC

Right image source: http://bit.ly/2xGWa3x

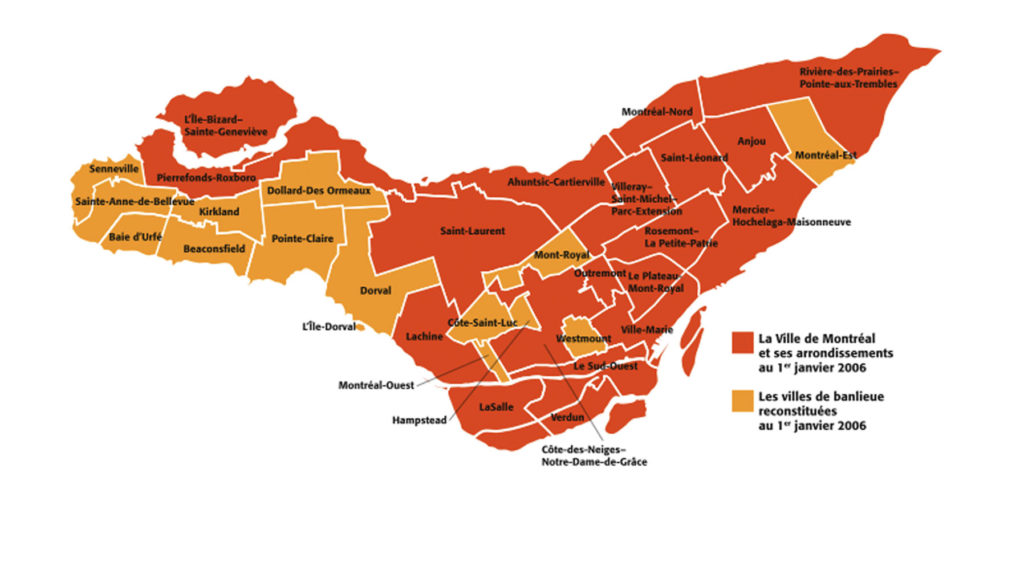

When Montrealers head to the polls on November 5th to cast their ballots in the municipal elections, it will mark the beginning of a seasonal trend: Quebec’s provincial elections are expected to take place in fall 2018 and the next Canadian federal election in fall 2019. The structure of municipal politics is peculiar on the island of Montreal: there are a total of 19 ‘merged’ boroughs, considered constituents of the Montreal agglomeration, as well as 15 ‘de-merged’ municipalities, most of which are suburbs concentrated in the West Island. Voters in the merged boroughs will vote for the mayor of Montreal, a city councilor for their borough, their borough mayor, and a borough councilor for their sub-district of the borough. Voters in the demerged municipalities will simply vote for the mayor of their municipality, and a municipal councilor for their sub-district.

It is worth noting that while political parties are present in Montreal’s municipal politics, they often revolve more around a set of priority issues and a city-wide mayoral candidate, rather than a fixed ideological alignment. This article will primarily focus on the Montreal mayoral race at large, and not those of individual boroughs or municipalities. Before examining the upcoming election, however, some attention will first be given to the recent history of municipal politics in Montreal, beginning with the actions of the Charbonneau Commission.

In 2011, the Charbonneau Commission was formed with the purpose of investigating the processes by which municipalities in Montreal were awarding contracts to construction companies, amid lingering allegations of corruption in prior years. By 2012, scarcely a year into its mandate, some of the revelations uncovered by the Commission pointed towards collusion on the part of Montreal mayor Gerald Tremblay and his Union Montréal party, quickly leading to his resignation and the end of his decade-long tenure as mayor. The following year, his interim successor Michael Applebaum was arrested on a total of 14 charges, most notably fraud and conspiracy; he was ultimately found guilty of eight of them. The final report delivered by the Commission in 2015 was quite damning, detailing widespread irregularities in the bidding and awarding processes of several major infrastructure contracts throughout the city, including bribery and other anti-competitive practices among construction companies.

When Montrealers took to the voting booth in the fall of 2013, they elected a former federal Member of Parliament, Denis Coderre, in a tight race: only 7 percentage points separated Coderre (32 percent) from the third-place candidate, Richard Bergeron (25 percent). Coderre achieved election in large part due to his promise to serve as a stable leader who would champion the interests of Montreal while ensuring accountability within his administration. The second-place finisher Mélanie Joly had adopted a similar message, but her achievement of 26 percent of the vote was especially impressive given her lack of prior experience in politics, as she had previously worked as a lawyer. Given that neither the first nor second place party had existed prior to the election campaign- the Projet Montréal party headed by Bergeron finished third- it became clear that Montrealers wanted and expected change in their city government.

The Coderre administration ultimately did achieve the stability its predecessors lacked, avoiding any high profile arrests, but it was not without scandal. Coderre himself was accused of requesting police surveillance of a journalist who had investigated him and received widespread public backlash for authorizing the dumping of 8 billion liters of sewage into the St. Lawrence River in order to facilitate repairs. In substantial terms, however, the Coderre administration was marked by several positive trends, including decreasing unemployment, increases in infrastructure spending, and the recent designation of Montreal as a metropolis by the provincial government, granting the city greater independence. In the realm of PR, Coderre gained favour for his open support of returning baseball to Montreal as well as his jackhammer opposition to the controversial new community mailbox system imposed by the federal Conservative government. The system, which was to replace direct-to-door deliveries from Canada Post, had raised safety concerns for seniors and those with limited mobility; its implementation was ultimately halted in October 2015 following the election of a Liberal government.

Entering the 2017 election, Coderre looks to build off of the results of his first term alongside his Équipe Denis Coderre pour Montréal party, placing a sustained focus on infrastructure upgrades, urban innovation, and transparency in government. It is quite likely that a second Coderre administration would closely resemble the first: slow, steady progress with some interim headaches- in the words of the mayor himself, “short-term pain, long-term gain.”

Coderre’s principal opponent, Valérie Plante of the Projet Montréal party, has decided to target the nuisances of this short-term pain to great effect, centering her campaign on overhauling the notorious inefficiencies of municipal construction projects in Montreal. Perhaps the most ambitious aspect of Plante’s campaign is her desire to commission a new metro line, the ‘pink line’, which would run diagonally from Bonaventure station all the way to the northeast of the blue line; public transit in general is a core focus of Plante’s campaign and that of Projet Montréal. Projet Montréal has also vowed to shed light on the expenditures incurred by the Coderre administration in the Montreal 375th anniversary celebrations, which took place throughout 2017 and were the subject of some controversy.

https://flic.kr/p/8Mf67b

All aspects considered, Coderre appears to have the slight edge one month out from election day. While his proposals are generally more modest than those of his main opponent, their lack of grandiosity may prove to be an advantage: Montrealers would do well to side with certainty over ambition, given recent history. The shadow of widespread corruption does not loom over Montreal’s municipal politics in the way that it did in 2013, in part thanks to Coderre, so it seems unlikely that Montrealers will opt for radical change.

Plante’s chances of victory rest on her ability to market herself and achieve a level of public notoriety similar to that enjoyed by Coderre, all whilst assuring voters of the viability of her transit proposals. The ‘pink line’ proposal would come with a multi-billion dollar price tag at the minimum, meaning provincial and/or federal funding would undoubtedly be required. Plante will have to convince voters that she possesses the negotiation skills to successfully lobby Quebec City and Ottawa to back the new metro line, as well as any other projects that may need support from the higher levels of government.

As a former federal MP and the incumbent mayor who secured metropolis status from the Quebec government, Coderre has already demonstrated his ability to navigate the multiple levels of Canadian politics. That said, moderate proposals can prove quite difficult to sell compared to the large-scale promises being made by Plante and Projet Montréal. To secure a victory, Coderre will need to find a way to discredit the feasibility of the pink line and other projects, while offering voters more realistic alternatives. If he falls into the trap of over-inflating his campaign platform in an attempt to keep a pace with Plante, Coderre’s prospects will prove bleak, as his opponent has maintained a fairly steady platform since her selection as the leader of Projet Montréal last year.

Recent opinion polls do reflect a close race, with high voter indecision; the last few weeks of the campaign may yet be the most important. It remains to be seen whether or not the steadiness and pragmatism of Denis Coderre will achieve re-election, or whether Valérie Plante will ride the pink line all the way to city hall.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi