Paris 2020: The US Election and the Fight Against Climate Change

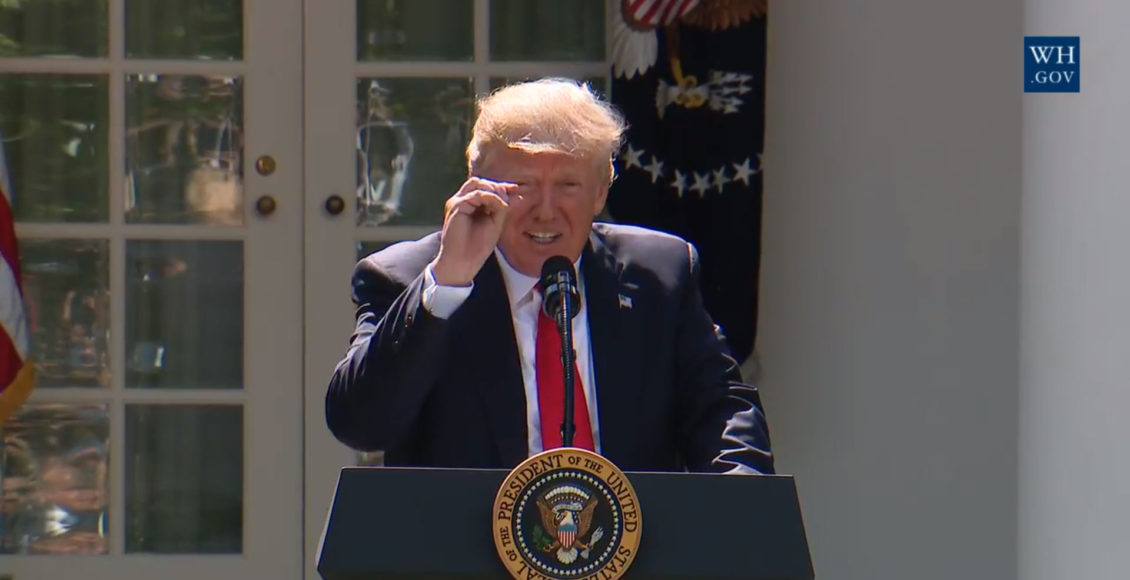

"Donald Trump Regarding the Paris Accord and Temperature" by The White House is licensed under public domain.

"Donald Trump Regarding the Paris Accord and Temperature" by The White House is licensed under public domain.

On November 4th, 2019, the United States began the process of withdrawing from the Paris Agreement. The official withdrawal will take place exactly one year from the announcement, which is conveniently also the day after the US’ 2020 national election. Given the proximity of the two events, is there potential for a change in government to affect the process, or even prevent the withdrawal altogether?

The Paris Agreement is the first global deal addressing greenhouse gas emissions; its member countries must stick to specific targets of reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The United States is the first of its 197 signatories to leave the agreement. The US government justified their withdrawal with a statement stating that its targets impose an “unfair economic burden” on workers, businesses, and taxpayers, claiming that the country has already reduced its emissions by 13% since 2005 and will continue doing so while also prioritizing the economy. However, the US’ actions on climate change remain “critically insufficient” relative to the terms set in the agreement, which mandate that each country create specific emissions targets that will allow them to reduce global warming below 1.5˚C by 2030. The US actually experienced a 3.4% increase in emissions in 2018, showing that the administration’s claims of reducing emissions were false. Even before their withdrawal from the agreement, the Trump administration had stopped adhering to Obama-era policies that were in line with its goals, namely one that had intended to cut emissions from fossil fuel plants by 32%. This is particularly damaging considering that science suggests President Trump’s “America First” strategy, characterized by support for the fossil fuel industry, will only worsen the United States’ greenhouse gas emissions.

The withdrawal has also damaged American diplomatic relationships, attracting accusations from other countries that the US is avoiding its responsibilities as a world leader. The agreement requires that developed countries do their part to help less developed countries combat climate change. As one of the richest countries in the world, the US was one of the original leaders of this initiative: other original members now feel as though they have been abandoned. In the face of this perceived betrayal, other members aim to stick to their commitments and have united against Trump’s decision, harshly condemning American climate change denialism while promising new initiatives to combat climate change in order to make up for America’s lack of action. In addition to Trump’s past statements calling climate change a “hoax”, the US has the world’s third-highest rate of climate change denial, in contrast with most of its international allies.

As well as criticism from the international community, the approaching American presidential election has led to harsh condemnation of climate change denialism (having become a largely Republican position in the past two decades) closer to home as well. Many of Trump’s political rivals, including Democratic presidential hopefuls, have publicly opposed his decision, and have called on him to recognize the urgency of reducing emissions. However, even a Democratic victory in 2020 would not prevent the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, since Trump would remain in office until early 2021. That being said, it is true that the new president always has the option of rejoining the agreement—they would simply need to submit new climate commitments to the UN, and would be back in the agreement within 30 days.

Looking at the current political landscape, all 16 Democratic candidates plan to rejoin the agreement if elected, and many plan to begin doing so on their first day in office. 11 candidates, including frontrunners Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren, have already put forward new emissions targets, all of which would go further than the original Paris goals. Thus while the increase in emissions that has already been caused by the Trump administration would not be prevented, a new president would be able to work to counter the damage.

No matter who the next president is, climate change is sure to be a critical issue in the 2020 election and has already been discussed at length by Democratic candidates. A February poll suggested that the climate crisis is among the top issues for Democratic primary voters and that 84% of voters think all candidates must have a clear plan to help the US transition to 100% clean energy. Overall, 70% of Americans profess to believing in climate change, a statistic that has increased by 9% since 2018, showing that Trump’s denial is an increasingly unpopular stance. However, considering data shows that Trump has a significant chance of winning on purely economic grounds, these statistics on climate change may not be enough to cost him the presidency. Statistically, far more Democrats care about preventing climate change, while Republicans’ greater concern is the potential financial costs of clean energy. Trump’s base is likely to ignore any disagreements they may have with him over the environment in favour of the economic success he promises them.

If Trump were to hold onto the presidency for a second term, there is skepticism as to how Democrats and American environmentalists could work independently to prevent the climate crisis. Many Democratic state legislatures have promised emissions reduction targets of their own. Governor Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania, the third-largest greenhouse gas emitting state, set a goal of reducing emissions by 80% before 2050, thus aligning with Paris targets. Newly elected Democratic governors in Maine, Nevada, and New Mexico (all previously Republican states), have also stated their commitment to passing emissions reduction bills that had been rejected by their Republican predecessors—one in Nevada commits the state to getting 50% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030. Another major player is the US Climate Alliance, a growing coalition of 25 state governors who have committed to upholding the original terms of the Paris Agreement after the federal government’s withdrawal. While the rollback of federal environmental policy will allow Republican states to ignore climate change if they wish to, Democratic states are putting in more effort than ever in order to counter the increased emissions caused by Trump’s policies. This shows that the country remains deeply divided over the issue, with one party’s increased regulations aiming to outweigh the other party’s increased emissions. But state Democrats have shown the necessary ambition for the fight against climate change, embracing the party’s pro-environment stance.

Congressional Democrats have shown further initiative as well. In May 2019, the House of Representatives passed a bill requiring Trump to keep the country in the Paris Agreement—although the bill was rejected by the Republican-controlled Senate. However, House Democrats nevertheless have continued working to ensure that climate change remains a key issue in Congress. Notable members of Congress, including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have drawn up the Green New Deal, an extensive congressional resolution, which offers a grand plan for reducing greenhouse gas emissions while ending societal inequality. While the deal was defeated in the Senate, its proposals are still supported by many Democrats, including many of the 2020 presidential candidates, several of whom co-sponsored the deal. It does remain divisive among the Democratic electorate, with nearly half supporting it while others consider it too extreme or unrealistic. However, it has opened up new dialogue about the societal change that will be required in the coming years, particularly if Trump remains in office. Changes to the configuration of the Senate in 2020 may also give House Democrats a greater chance of passing anti-emissions legislation in the future. Democrats understand the importance of winning back the Senate in 2020, and control of Congress will be a key factor in the future of climate change legislation.

The US has much at stake in 2020, and while the presidency is the question at the forefront of most people’s minds, the importance of state and congressional leadership remains a factor in the future of climate policy as well. A change of president would certainly be the easiest path towards the US returning to the Paris targets, and the US returning to a position of climate leadership would definitely be a source of reassurance for the international community. However, action at the state level has shown that change can come from many parts of the political system, and most Americans are not ignoring the reality of the climate crisis—only time will tell if they will be able to translate their feelings into votes before it’s too late.

Edited by Hannah Judelson-Kelly.