PART I: The Allure of Modern Escapism

This photograph by Bicanski is licensed under CCO.

This photograph by Bicanski is licensed under CCO.

A few months ago, my phone was stolen — which, for many students living in the Milton-Parc neighborhood of Montreal, seems to be a common occurrence. Like others who have experienced this, I was initially startled, tracking my device on FindMy and scrambling to file a police report. But, after a momentary panic, I was surprised to find myself overcome by an intense peacefulness and serenity. Swept up in a nostalgic reverie, I spent the next couple of days imagining myself leading a simpler life with no desire or need to use my cellphone, silently wishing it would never be found. I felt truly present and alive, engaged in lively discussion with friends, seeking gratification beyond my fingertips through nature and elaborate forms of exercise. I even slept better, allowing myself to truly sit with my thoughts and explore the untapped corners of my mind rather than retreating into the comfortable escape of mindless scrolling. Inspired by my own personal revelation, the two weeks I spent without my phone made me seriously question the need for such intelligent devices constantly at our disposal. Could it be that our smartphones are robbing us of the full authentic human experience on a broad societal level? Were these devices ever even designed with our best interest at heart?

In a recent New York Times article from December 2022, journalist Alex Vadukul shone the spotlight on a group of Brooklyn teens who express many of the sentiments felt by me and other young people. Identifying themselves as the “Luddite Club”, these teenagers choose to spend their time discussing books and philosophical questions rather than chasing the dopaminergic rush of receiving likes on Instagram. They desire to be completely purged of their smartphones, craving a more fulfilling life as envisaged by the likes of Chris McCandless and Henry David Thoreau. In an act of pure defiance, these teens reflect the desperation of growing up in an age where intellectualism and creativity are stifled by our confinement to our phones.

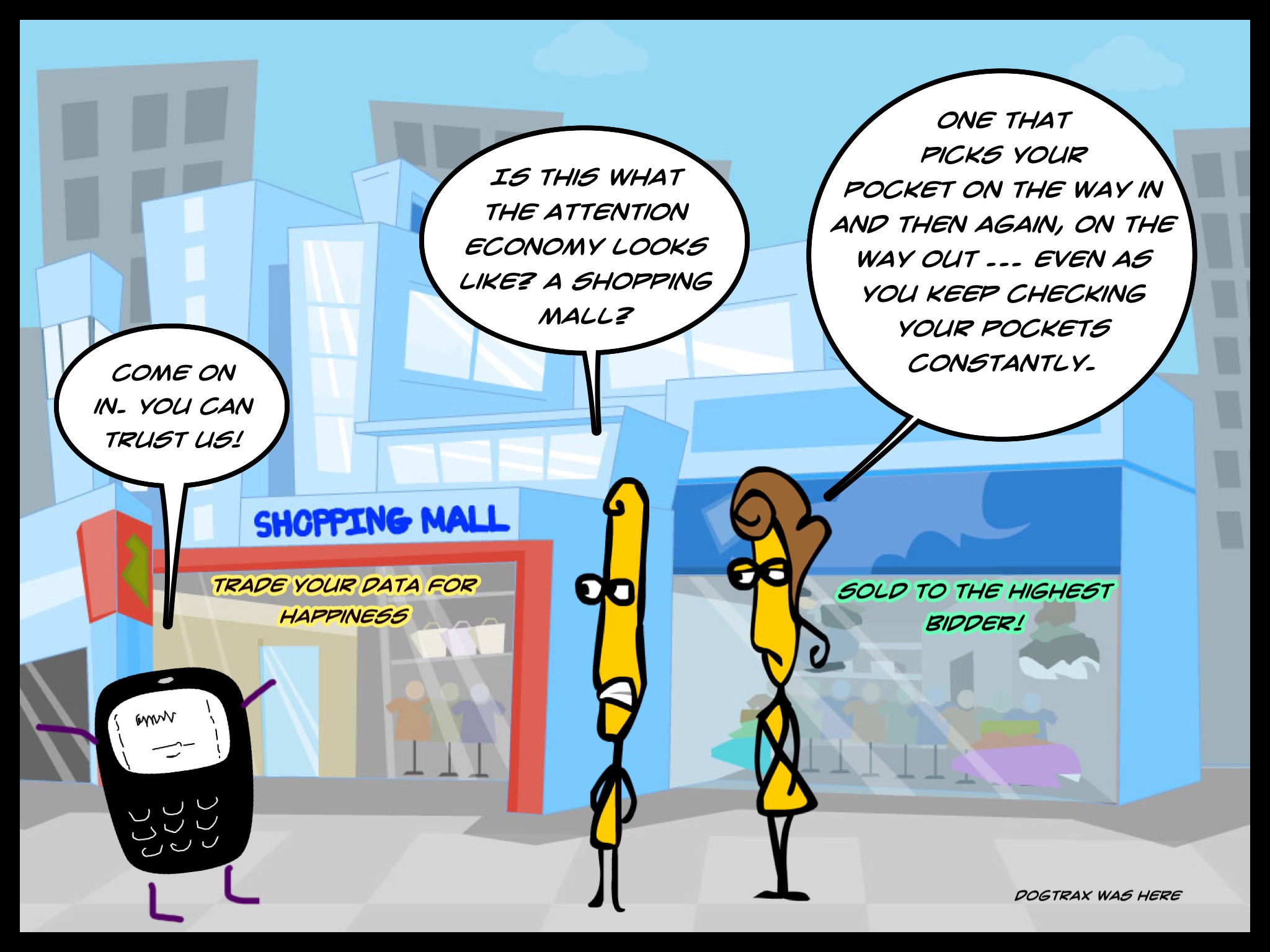

Retreat from our phones and social media is far from easy due to deeper forces at play. Technology companies design social media algorithms with the intent of keeping users glued to their screens, monetizing the time people spend on their sites to maximize company profits. In recent years, apps like Facebook and Instagram have rapidly accelerated their use of targeted ads to ensure longer viewership. While these platforms originated as photo-sharing sites amongst close connections, they have now become shrouded by a tsunami of ads and influencer content that block users from seeing photos of personal connections, distracting their awareness away from friends and family to more materialistic endeavors. Social media sites seeking to increase revenue bombard users with a carefully calculated diet of targeted ads, competing for our attention and monetary value for the sake of driving company profit. Their tactics are far from neutral, enticing us to behave in certain ways that directly impair our productivity and mental health. Instagram and Facebook algorithms ensure that messages, photos, and likes arbitrarily pop up on our devices, cajoling us to compulsively check for them to receive a dopamine hit. Explicitly taking advantage of our reward pathways, UX design tools use behavioral psychology tactics of intermittent variable rewards to reinforce dopamine-seeking behavior. While users often engage in these checking tasks with the intention of taking a quick glance, research shows that these minor interruptions tend to escalate, resulting in an average of 25 minutes of scrolling before returning to one’s original task. As users, there comes a point where we must stop to question whether these apps are truly serving us, or simply taking advantage of our psychological vulnerabilities to undermine our agency.

Technology is used in myriad ways to commodify the human experience, capitalizing off of access to our personal data and time. More than 20 years ago, journalist Michael H. Goldhaber wrote about the “attention economy”, a phenomenon which makes social media companies wealthier at the expense of users’ well-being. Advertising companies that use user data to target consumers more precisely function based on an underlying profit incentive that essentially turns human agency into “a new form of automaticity- a lived experience of pure stimulus-response” (Zuboff, 82). Consequently, Goldhaber emphasized that “increasing demand for our limited attention [keeps] us from reflecting, or thinking deeply (let alone enjoying leisure)”. According to the Newport Institute, “89 per cent of college students experience moderate or severe anxiety and fear when they don’t have their phones with them.” In effect, our devices are manipulating and controlling our fragile mood states. As Dr. Don Grant puts it, “when you are mindlessly scrolling, you are an ‘absent presence’—that is the zombie state. You’re missing opportunities for connection, experiences and real-life engagement.” Companies like Facebook and Instagram know this, but continue to subject their users to attractive content as a baiting tactic to reel them in like a fish on a hook.

Essentially, users become paralyzed in the emergence of a powerful “Big Other,” which, according to Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of surveillance capitalism, controls and alters daily human behavior. The collection of personal data, according to Zuboff, serves to strengthen a “dystopian” surveillance project. As she reveals, “Google’s tools are not the objects of a value exchange. They do not establish constructive producer consumer reciprocities. Instead they are the ‘hooks’ that lure users into extractive operations and turn ordinary life into the daily renewal of a 21st-century Faustian pact,” thus breeding a social dependency (Zuboff, 83).

As companies like Google exploit this asymmetrical power dynamic, it should come as no shock that the social media platforms we use on a daily basis play a similar role in actively eroding our well-being. As a society, it is in our best interest to vouch for the adoption of ethical software designs that put moral integrity above profit motive. In defiance of their authority over us, we can claim some of our agency back by engaging in other more fruitful activities. Nowadays, I try my best to be conscious of the amount of time I spend on my phone, so that I am not robbed of abundant experiences in the physical world. In our contemporary reality, actions like reducing our screen time, opting for flip phones, and picking up a book have become the greatest form of rebellion. In the spirit of the “Luddite Club,” liberating ourselves from Silicon Valley’s iron hand may be our golden ticket to unlocking a happier, more fulfilling life. Why should I, or anyone, continue to support technology companies that could care less about our well-being?

This article is part of an MIR series on the ethics of AI. To continue reading, click here.

Featured Image: This photograph by Bicanski is licensed under CCO.\

Edited by Sara Parker.