People Before Highways: How American Roads Tore Apart Neighbourhoods

Discover the truth about America's highways...

American suburbia is a defining feature of the American dream. One where a suburban wasteland marked by a white picket fence, a freshly mowed lawn, and two family cars parked in the driveway is the hallmark of individualistic success. The rise of this cinematic reality came true in the 1950s, a postwar world which found American nationalism on top. It was good to be an American. Greater urban areas grew into what would become American suburbia, popularized by William Levitt, the father of modern suburbia. Those who traveled into cities for work became known as commuters, however, the existing infrastructure to support their daily journey was largely inadequate. What was the answer to this problem? Automobiles. Previously exclusive to the wealthy, automobile ownership grew substantially as the dominance of General Motors and Ford took hold in the American economy. An infrastructure was needed to support this postwar boom, prompting the biggest infrastructure project in American history: the Interstate Highway System (IHS). Highways were then put in place throughout America, allowing commuters a direct aortic vein into urban areas where business and commerce could take hold.

When analyzing the Interstate Highway System’s effects on America’s economy and society, it is important to understand the mass migration of predominantly white citizens into American suburbia. This mass migration, often termed the “white flight,” took place in the second half of the 20th century. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the suburban population grew from about 40 million in 1970 to over 100 million by 2000. Research from sociologist Richard Florida highlights that during this period, many white Americans were driven to leave cities in pursuit of better schools, lower crime rates, and more spacious living conditions. The effects of this white flight were as direct as they were large, including expedited urban decay from lack of adequate tax revenue, increased racial segregation, and mounting economic disparities for people of color. However, economic disparities for minority groups were felt most acutely in American cities, primarily because of urban disinvestment and the niche reality of highway development dissecting and eliminating vibrant neighbourhoods. For many predominantly black and brown urban communities, the interstate highway building project was a death sentence to their future, one that continues to affect them to this day.

The Yellow Book

In the mid-20th century, America was on the brink of transformation. It was during this dynamic time that President Dwight D. Eisenhower, inspired by his experiences in wartime Europe and the logistical challenges faced by military operations, envisioned a revolutionary network of highways that would reshape the American landscape. This vision culminated in the establishment of the Interstate Highway System (IHS) in 1956, a monumental undertaking that connected cities, rural communities, and regions like never before. The system was conceived as a means to promote not only national defense but also economic prosperity and mobility.

As construction began, the American landscape began to change dramatically. The roar of construction machinery filled the air as engineers planned routes that would weave through mountains, across plains, over rivers, and into cities. Stretches of highways sprouted across the map of the nation: Interstate-95 commanded the East Coast, extending from the Canadian border with Maine all the way to Miami, and Interstate 90 reached across time zones and connected those in Seattle with that of Red Sox loving Bostonians. Communities that had been isolated now found themselves connected to major urban centers, with a total of 41,000 miles of roadway connecting over 90% of America.

All of this innovation came at a hefty price — construction costs totaled 114 billion USD ($500 billion today) to build and maintain the IHS through 1991. This price tag left many in Congress hesitant about approving a highway system that had been proven to be only effective in Germany, a country the United States had destroyed just years prior. However, it was the release of the “Yellow Book,” issued by the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO), under the direction of its leader, that helped shift opinions. The book provided detailed illustrations of how the new highway systems would integrate into metropolitan areas, specifically identifying neighbourhoods, routes, and connections for new spurs, belts, and offramps. The Yellow Book is largely hailed as the guiding force that motivated Congress to approve funds for the IHS, as it allowed Congress to visualize and understand the benefits of the proposed highway system.

“Urban Blight”

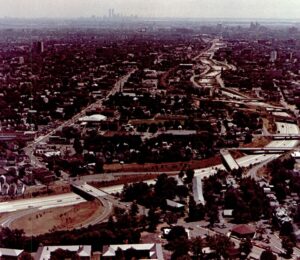

While Congressional leaders were visualizing American innovation, city residents were seeing the effects of total destruction and geographic segregation on underserved, majority-minority neighbourhoods across the nation. In areas like the Western Addition and the Fillmore District of San Francisco, communities experienced destructive redevelopment with minimal pushback, leading to irrevocable changes that dismantled the cultural fabric and vibrancy of the neighbourhoods. The Rondo neighbourhood of St. Paul, Minnesota, primarily composed of Black and brown residents, was destroyed by the I-94 project, culminating in the loss of 300 businesses and the displacement of 600 families from their homes. In many cases, white leaders—at the city, state, and federal levels—strategically and purposefully routed infrastructure projects through majority-minority neighbourhoods, knowing these areas would elicit less resistance and help curb what they called “urban blight.”

In New York, Robert Moses, one of the most prominent urban planners in American history and responsible for major construction in New York City and Long Island, said in a 1959 speech: “Our categorical imperative is action to clear the slums…we can’t let minorities dictate that this century-old chore will be put off another generation… we must go right through cities and not around them.” His statue still stands in Long Island today. This sentiment among urban planners was not confined to New York. President Eisenhower appointed an entire team of mostly white men in the 1960s who prioritized highway efficiency at the cost of low income housing. These highway projects’ effects were tangible: they worsened air quality, eliminated pedestrian walkways, physically darkened neighbourhood streets with road overpasses, and sank property values— perpetuating a cycle of poverty in Black families. In total, estimates from the U.S. Department of Transportation concluded that more than 475,000 households and over one million people were displaced nationwide by federal roadway construction projects.

Instances of neighbourhood levelling occurred far too often in the United States after the passage of the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act. However, there were success stories of neighbourhoods banding together to oppose the destruction of their communities. In Boston’s vibrant Jamaica Plain neighbourhood, environmental activists, residents, colleges, and city leaders came together to oppose the belt construction of the South West I-95 Expressway. The proposed plan included an eight-lane interstate expressway belt that would have cut through various Black communities, including Hyde Park, Roslindale, and Jamaica Plain.

From 1966-1969, protests drew crowds, sometimes numbering in the thousands. These events were dubbed “Beat the Belt” rallies, and one particular rally became known as the “People before Highways Day” held on the Boston Commons, a main park in the city centre. On July 15, 1969, Chuck Turner, a city council member, held a press conference with statements from fourty Black activist groups and triumphantly announced: “There will be no inner belt through our community.” The communities had won. Black activists had successfully defeated the federal government and institutions that had been determined to remove their homes, and by extension, their existence. From the displacement of families and the destruction of real neighbourhoods to the reinforcement of racial segregation and environmental injustice, the Interstate Highway System left a profound mark on the fabric of American society- for better or for worse.

In Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play, A Raisin in the Sun, the Youngers, a Black family, live on the South Side of Chicago. They face institutional racism, their struggle for a better life, symbolized by their father’s dream of buying a home, represents the harsh reality of class mobility as a Black American in the 20th century. In their Chicago apartment, Mama, the family matriarch, has a small plant that sits on the windowsill of their kitchen. The plant, unable to get enough sunlight, dies – much like Mama’s dreams. Why? Outside their window, a roaring highway dominated and darkened their apartment and neighbourhood, blocking the light.

Edited by Alexandra Agosta-Lyon.