People Power Revolution: The 35th Anniversary

On February 25, 1986, the People Power Revolution ousted Ferdinand Marcos from Malcañang Palace and lifted Corazon (Cory) Aquino to the presidency, inaugurating the most recent chapter of Philippine democracy. By ending nearly 14 years of dictatorship through non-violent means, People Power demonstrated the transformative potential of mass political participation and influenced revolutions elsewhere, including Poland and Indonesia. As the Philippines continues to be emblematic of broader trends towards populism and democratic backsliding, the anniversary of democracy’s return offers an opportunity to remember the Marcos dictatorship and reflect on the legacy of People Power.

Although Marcos had been legitimately elected president in 1965 and 1969, constitutional term limits prohibited presidential tenures longer than eight successive years. Accordingly, in order to extend his presidency, Marcos exploited the social unrest of student protests and increased activities of communist and Muslim insurgents to establish martial law on September 21, 1972. Facilitated by martial law’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, political opponents and dissidents were not only arbitrarily arrested and incarcerated, but also subject to major human rights abuses and even extra-judicial killings. Historian Alfred McCoy, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, estimates that over 3,000 people were killed, 35,000 tortured, and 70,000 arrested over the course of the Marcos dictatorship. Furthermore, despite Marcos’s promise of economic development and growth, he emerged as one of the most corrupt dictators in history. By exploiting the national treasury for personal use and establishing a system of crony capitalism that generated monopolies for his family and friends, it is estimated that he embezzled at least $10 billion USD. The Marcos era consequently heavily indebted the Philippines and devastated its economy; efforts to repatriate stolen assets continue to this day. Moreover, it is worth noting that Marcos retained American praise and support throughout his authoritarian era.

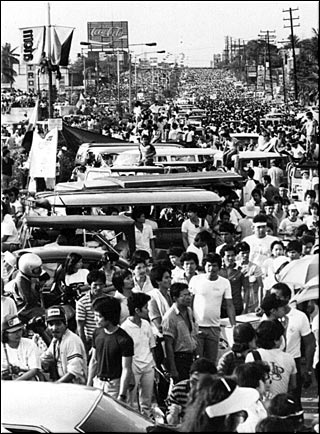

While Marcos officially suspended martial law on January 17, 1981, its policies continued to be practiced, and support for Marcos waned. Anti-Marcos sentiments gained even greater traction on August 21, 1983. Following a self-imposed exile in the United States, Benigno (Ninoy) Aquino, Marcos’s primary political opponent and husband of future president Cory, was assassinated as he stepped off the plane at Manila International Airport. In turn, Aquino’s murder struck a chord within the Filipino people, leading to a seven million strong funeral procession and the beginning of a series of events that would culminate with the People Power Revolution. Amidst this outpouring of support for his political opponent, Marcos announced snap elections for 1986 in an effort to stabilize his position and exploit the opposition’s disorganization. However, the recently widowed Cory Aquino emerged as “the unifying moral symbol of opposition to Marcos” and, at the urging of Cardinal Jaime Sin, declared her candidacy for the presidency on December 3, 1985.

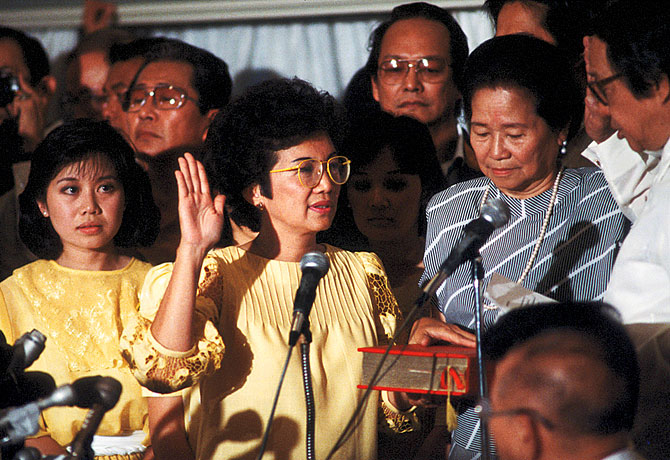

As Marcos attempted to steal the election through fraud and vote-rigging, Cory and her supporters began “a national campaign of civil disobedience” in response. Simultaneously, dissident military elements known as the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), frustrated by Marcos’s politicization of the armed forces, made plans to stage a coup and seize power. As the Marcos regime caught word of the RAM’s intentions and dispatched loyalist forces to dispel the insurrection, Cardinal Sin and other leading figures called on the Filipino people to take to the streets and demonstrate their support against Marcos. Citizens lined Manila’s Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) and placed themselves between the opposing military forces to prevent any violence, offering soldiers flowers, food, and prayers. Despite Marcos’ orders to disperse the crowds, even by violent means, significant numbers of military personnel refused and defected to the opposition. As Marcos lost control of the armed forces and crowds massed at the presidential residence, American allies evacuated the former president and eventually brought him to Hawaii. Meanwhile, Aquino was sworn in as president on February 25, 1986, and Philippine democracy was restored.

Despite the tremendous achievements of People Power, the ideals of liberal democracy have yet to be realized. Although democracy’s return has improved the country’s economic outlook, social and political issues of inequality, corruption, and an “elite democracy” remain pervasive. It is evident, therefore, that the mass political participation of 1986 has yet to translate into improved political representation and effectiveness. The issues that have plagued the country for generations continue to persist. Nonetheless, these shortcomings do not mean that People Power was a failure or that it was harmful. By ending the authoritarian rule of Ferdinand Marcos, the movement offered a political opening for change and growth. It allowed the workings of democracy to return and provided a glimmer of hope for a better future. However, internal coup attempts marred Cory Aquino’s presidency and obstructed the momentum for reform. In turn, Aquino’s actions as president can optimistically be seen as defending democratic proceedings at the cost of implementing reform or pessimistically as perpetuating elite domination. Regardless, even if the procedural aspects of democracy were protected, its substantive problems remain prominent and disheartening. As Philippine democracy continues to backslide, exemplified by the recent “Anti-Terror Bill,” and pro-Marcos propaganda lingers, disillusionment vis-à-vis People Power becomes an easy sentiment. Amidst a popular drug war that has killed more people than the Marcos dictatorship and the return of autocratic rule, perhaps the revolution’s inability to initiate major, systematic change has pushed people to entertain anything that disrupts the status quo of elite democracy.

Throughout their country’s democratic backslide, Filipinos have paradoxically shown significant support for strong, autocratic leadership as well as a resilient commitment to the democratic process. In turn, the substantive problems of elite democracy may have disappointed citizens so deeply that many are willing to abandon democracy in all but name. While Duterte may not have ambitions to extend his own presidency, the groundwork for a new political dynasty is potentially being laid, leaving open the possibility that his vision of autocratic rule will extend far beyond his tenure. Consequently, given the significant weaknesses that enabled Duterte to co-opt and exploit the Philippines’ political system, it is clear that the country’s democratic institutions require extensive reform. As McGill University professor Erik Kuhonta notes, personalistic, strong-man politics characterizes every level of the Philippine government and is ultimately personified in the incumbent president.

Accordingly, political parties must become more than “mere caricatures” that are primarily vehicles for patronage and patrimonialism. The rampant corruption must be rooted out and government positions must carry a deeper purpose than the potential for self-enrichment. To do right by Filipinos’ dedication to democracy, the ideals of duty and service must manifest amongst the country’s elected officials. Political parties, therefore, must become programmatic and principled in order to implement the progressive reforms that would enable the emergence of a government that is more representative of its people. The Philippines’ most pervasive issues require extensive, systematic change and, despite its prominent flaws, the government retains the greatest capacity to mobilize the resources required to rectify the situation and achieve the People Power movement’s vision.

Ultimately, the memory of People Power should not be what failed to come afterward but what opportunities it offered for the future. The Philippines may take great pride in its status as Southeast Asia’s oldest democracy, but the reality is that the current edition of Philippine democracy is very much in its youthful stages. As Professor Kuhonta recognizes, the entrenchment of effective, rational-legal institutions is a product of long, historical processes. The failures and shortcomings of Philippine democracy, therefore, should not define how we remember People Power. Rather, the memory of People Power ought to be inspiring, and its legacy a testament to the ability of an active, passionate citizenry. Regardless of the failures of politicians since then, the People Power Revolution remains an important symbol of the strength, determination, and faith of the Philippine people, and it should serve as an impetus for renewed efforts towards achieving the ideals of liberal democracy.

Featured Image: “EDSA 1986 flowers for soldiers” by princesse_laya is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Justine Coutu