Poland’s Recent Abortion Ban

The PiS, the Catholic Church, and the Denial of Basic Human Rights

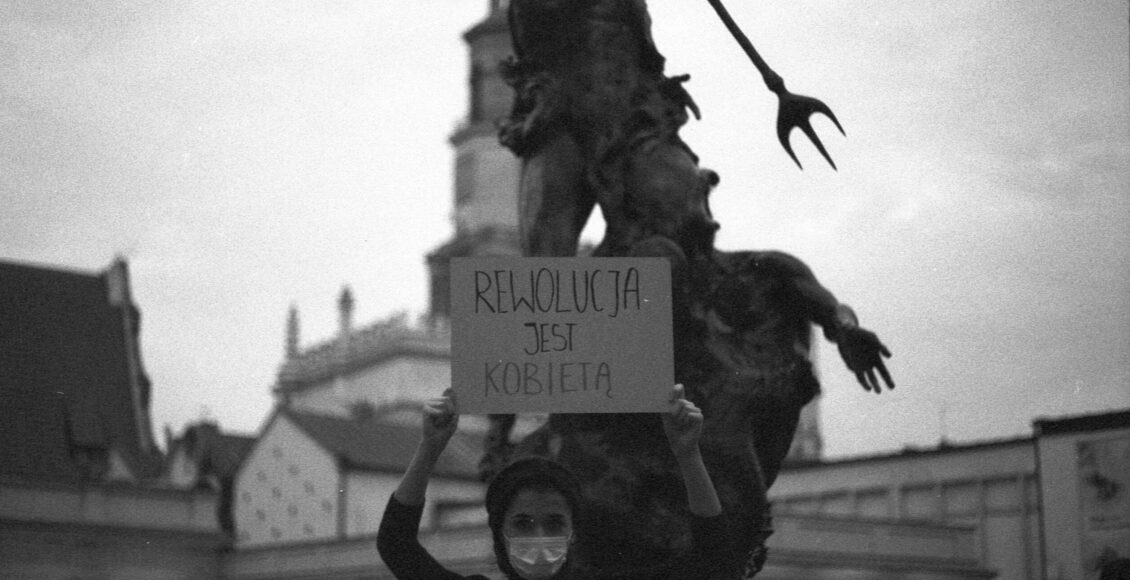

“Revolution is a woman” by Bohdan Bobrowski is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

“Revolution is a woman” by Bohdan Bobrowski is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Known to be a conservative Roman Catholic nation, Poland has long been home to fierce debate over abortion rights, with the two opposing sides consisting of traditionalists and those advocating a more progressive agenda. Tensions reached an all-time high last October, as the country’s Constitutional Tribunal ruled to further increase the restrictions on legal abortions. Already, Poland had some of the most stringent abortion laws in Europe, with it being legal in only three cases: fetal abnormalities, a direct threat to the woman’s health, and rape or incest. In a decision made on October 22, 2020, however, the court declared abortions in the case of congenital defects illegal, on the basis that the Polish Constitution protects human life. Considering that out of the mere 1,100 abortions that legally occurred in Poland last year, 98 per cent of them were for this reason, such a decision essentially ensures that those seeking abortions will either be forced to leave the country or perform them at home, both of which will put their health at risk and leave them vulnerable to legal prosecution. Already, women’s rights groups estimate that between 80,000 to 150,000 citizens get abortions outside of Poland’s health system each year.

The announcement prompted a response from hundreds of thousands of the nation’s citizens, leading to some of the largest protests in decades. In the first week alone, 430,000 people participated in over 400 different marches all over the nation. After nearly two weeks of constant demonstrations, the law’s implementation was halted following the government’s failure to officially publish the decision prior to the November 2 deadline. Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, offered to find a “compromise” legislation in which the law would exempt fetal abnormalities considered deadly. In an unsurprising response, activists refused, highlighting their unwillingness to negotiate on an issue that so significantly impacts their lives. Nonetheless, in an abrupt decision by the court, the law was brought into effect on January 27, triggering massive outrage around the country and leading human rights advocates to state that “the state wants to further limit their rights, risk their lives,” and essentially take away their say within society. This recurring fight for women’s basic rights is bigger than simply having legal access to abortions; it is a representation of Polish women’s refusal to continue being controlled by conservative, “increasingly autocratic” regimes like the right-wing Law and Justice party (PiS) currently in power, as well as the Catholic Church.

Although recent events have brought it to international attention, Polish society has been divided for years, and especially so since the 2015 election of the PiS. Led by party chief Jarosław Kaczyński, PiS has long defended the country’s traditional Roman Catholic values, using such ideals in its policy formation. Their leaders have even labeled opponents as “anti-Polish and anti-Christian” and branded women’s rights activists as “dangerous agents of liberal Western propaganda,” neither of which are substantiated claims. In 2016, Kaczyński made a statement that further explains the party’s position on the recent law, declaring that even if a fetus with defects was sure to die upon its birth, the mother should still carry it to term, have it baptized, named, and then buried. This utter lack of respect regarding women’s personal health and rights over their bodies has largely motivated the protesters fighting for this party to be ousted from the government.

The past months of protest have made evident the deep-seated ideological divisions in Poland, largely revolving around the culture of the Polish state. Marta Lampart, lawyer and one of Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet’s leaders (All-Polish Women’s Strike, OSK) believes that this “is a whole backlash against a patriarchal culture, against the patriarchal state, against the fundamentalist religious state, against the state that treats women really badly,” a statement that applies to more than just abortion. OSK has fought for other polarizing issues that are in drastic need for change, including the protection of women’s and LGBTQ+ rights, the separation of church and state, improved healthcare, and judicial independence, to name a few. Citizens are becoming increasingly aware that Poland is “years behind” in ensuring basic human rights, and are protesting for an end to the church’s involvement in political affairs, such as its undue politicization of topics such as abortion.

For years, the Polish church has influenced teachings and laws about conception, contraception, and abortion, effectively impacting its citizens’ understanding of such concepts and limiting the development of their own beliefs on these matters. In the recent elections, the power held by church officials was seen through the involvement of priest Tadeusz Rydzyk. This well-known cleric provided his support for the party, practically assuring them millions of votes, and in return for this loyalty was promised legislation he favoured, including the removal of all sexual education classes. As explained by the president of the Polish Institute of Public Affairs, the church has an unbelievable amount of power, especially in smaller rural regions, thus allowing them to essentially “shape politics as they like.” This mutually assured alliance, while beneficial to the PiS and the church, sacrifices thousands of citizens’ rights.

This close relationship between the conservative government and such a highly influential religious institution has for years posed a threat to secularism within the nation, a fact highlighted by Kaczyński’s statements that he believes Christianity is fundamentally connected to the Polish national identity. The 2020 presidential elections between Duda, a member of the PiS, and decidedly more liberal candidate Rafał Trzaskowski further entrenched divisions in the country, particularly generational ones. Duda was largely elected by the older population, whose political beliefs tend to be shaped by patriarchal and conservative Catholic values. With newer generations becoming increasingly active in political matters, Polish support for the church has lowered from 90 per cent in 1989 to 41 per cent today. This distancing from the church by younger Polish citizens does not come as a surprise, as advocates for this political shift are made up of women’s rights activists, left-wing lawmakers, and liberal protesters fighting for a secular Polish state. Following the Tribunal’s decision on abortion, these same Polish activists introduced a proposal to liberalize abortion. It must now receive 100,000 citizens’ signatures to be presented for debate at the assembly, and while this is largely possible considering the number of protesters in recent months, it will undoubtedly not pass once in the hands of the government. Nonetheless, even having the proposal debated in Parliament would be a positive move, as they aim to start a much wider discussion regarding the protection of human rights more broadly.

The contested issue of abortion is representative of a much larger matter revolving around the corruption present in the country’s institutions. Considering that such occurrences are rooted in the country’s culture and decades of religious upbringings, change will only occur when the system itself begins to reform. The younger generation’s evolving beliefs in comparison to those prior are a hopeful start to such advances, marking a solid beginning to a possible separative transformation of Polish political and religious affairs.

Featured image “Revolution is a woman” by Bohdan Bobrowski is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Edited by Selene Coiffard-D’Amico