Politics of Identity, Not Identity Politics

Rethinking Gender, Orientation, and Race in Selfhood

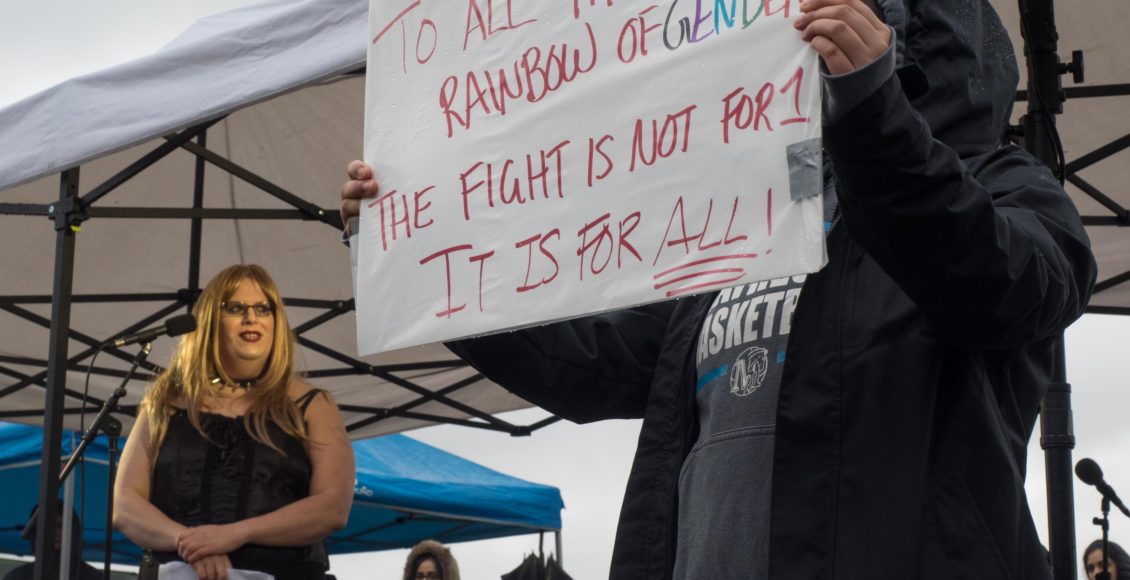

Taken by Sally T. Buck

Taken by Sally T. Buck

Progress — we’ve seen it. Or, we had been seeing it: steps in the right direction toward equality. With post-modernism came resistance to the normativity that had restricted freedom and limited selfhood. The turn of the century seemed a pivotal point for equal rights: same-sex marriage became accepted and legalized in almost 30 countries around the world and movements against racial discrimination gained more and more momentum.

The first protests for gay rights in Canada were in August 1971, two years after homosexual acts were decriminalized between consenting adults. In 1973, the first national Pride Week was held. This was the same year that homosexuality was removed as a “disorder” in the Diagnostics and Statistics Manual. In 1979, Montreal and Vancouver hosted the first official Pride March. Throughout the decade, attention was brought to the inequalities carried out by law enforcement vis-à-vis gay and lesbian Canadians, most notably the historical “cleansing” attempts in Montreal prior to the 1976 Summer Olympic games directed by mayor Jean Drapeau. It wasn’t until over two decades later that the Canadian government actively sought out legal protection of queer rights, with Bill C-38 granting same-sex couples the legal right to marry in 2005.

It was only 5 years ago that the House of Commons passed Bill C-279, which extended human rights protections to transgender and transsexual groups in Canada. Despite decades of inching progress, Canada still suffers from very limited representation of non-heteronormative experiences in its political and social pursuits. Approaching 50 years after the official decriminalization of homosexuality in the country, why has progress slowed?

Canada’s process toward reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, for instance, has seemingly failed to incorporate non-heteronormative experiences. The national inquiry for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) was launched in 2015 to address the disproportionate number of disappearances of Indigenous individuals, and recently had its timeline extended to allow for a more thorough investigation. The panels held for this inquiry shed light onto society’s profoundly ingrained binary tendencies, and the lack of representation and visibility for those who don’t conform to these constructed norms.

The inquiry also seemingly excludes cases like that of Colten Pratt, a two-spirited man who disappeared in 2014, and has yet to be found. “Two-spiritedness” is a broad term coined in 1990 by Albert McLeod that encompasses a reference to an Indigenous person who adheres to a spiritual identity of gender and sexual fluidity. A translation of the Anishinaabemowin term “niizh manidoowag,” the term is not just an identifying label, but can be a traditional role. The usage of this term, and the inclusion of it in the name of the movement, LGBTQ2SIA+, can be seen as a response to outcry against the simplification of the goals of the LGBTQ2SIA+ movement. Critics of the mainstream gay rights movement mainly hold that there is internal discrimination within the minority group. It is argued that the resulting hierarchy of privilege is ignored and thus further consolidated by the monolithic singularization of the movement.

We have seen the evolution of the movement’s title: from “Gay Pride” to “LGBT” to “LGBTQIA+” and now “LGBTQ2SIA” which stands for “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, 2-Spirit, Intersex, Asexual, and Ally.” In the attempt to find a way to communicate about the issues in sexual rights, gender, and race, lines are drawn to define experiences. Some might argue that this leads to greater identity politics, which is most harmful when it allows for individuals to invalidate other groups’ struggles in power in comparison to their own. Perhaps the issue is not in the creation of terminology defining experiences of power relations, but the mentality that underlies the usage of this terminology to further divide them.

TJ Lightfoot and Jasmine Redfern, who work with a youth sexual network recently testified at a panel for the MMIWG inquiry in September, bringing attention to the limitations on policies that are meant to protect victims because but do not consider situations such as women fleeing from violence committed by other women. Their testimony urged for administrative systems not to erase LGBTQ2SIA+ individuals for the sake of convenience. According to Statistics Canada, while women as a whole are more likely to be victims of crime in Canada, lesbian women are twice as likely to become victims, and bisexual women are approximately four times as likely. This inclusion of sexual orientation and gender isn’t just to make a point—it is crucial for an accurate portrayal of the issues at hand. While male violence against female victims is statistically most prevalent, it is by no means the only occurring circumstance. The normalization and proliferation of this misconceived exaggeration demonstrates the use of statistics as a reductive measure. The misrepresentation of statistics and the failure to consult other other sources of information not only impedes our understanding of the current state of affairs. It also hinders our ability to effectively address these issues.

Historically, groups have forged social identity through comparison with the “other.” This has especially been true in colonial contexts. European expansion during the “exploration” era brought about encounters with cultures and societies that were different from Europe. These “discovered others” were labelled as “savage,” “uncivilized,” and “unintelligent,” to cultivate a sense of European superiority. Michel Trouillot1 calls this the “savage slot,” wherein a caricature of the “other” is created with an implicit and perhaps unconscious effort to create a foil of the European image. In doing so, differences are defined in terms of position on a linear path of evolutionary development that places White Europeans at the finish line. The legacy of this system leaves differences viewed not as benign, but as hierarchical. With the rise of post-modernism, critiques of this way of thinking emerged, giving hope that we had moved on from evolutionary models of humanity.

What is less discussed is the fact that post-modernism is, in itself, borne of modernist thought as a critique but also an extension of it. What would perhaps be the greatest mistake moving forward would be to limit ourselves and our understanding of selfhood by forgetting the ways in which we have come to that understanding.As Canada continues to dichotomize culture, race, gender and sexuality – and treat them as detached categories – the experience and humanity of its citizens and residents become compromised. The result is seeing people not for who they are, but for what they can be classified as, through a tainted lens of outdated stereotypes. The resulting misrepresentation impacts peoples’ identities and senses of selfhood. Perhaps, then, identity politics and the exclusivity of social movements are not a reflection of any inherent paradoxes in equality. Instead, they reflect a need to overcome the leftovers of an outdated mode of thought that separates equality into artificially conflicting categories.

The point is not to diminish or invalidate the progress that has been made thus far, or to suggest there is a singular solution to all social inequalities. Instead, it is to highlight how progress has been stagnated by viewing identities as mutually exclusive and conflicting. Perhaps we would see greater progress with regards to social issues if we could consistently and profoundly understand their inextricable nature. There are inconsistencies within each movement, where the highly interconnected nature of gender as well as sex norms, culture, and race, have proven these issues to be far more complex than initially discussed. The world is thus inherently intersectional: the lines we draw in our attempts to define our conceptualizations of ourselves, and of this world, are overlapping and interconnected. It is thus insufficient to discuss social movements in a unitary fashion— because social justice is not experienced in a unitary fashion.

Steps like same-sex marriage are a good start, but the legalization of customary institutions is not the same thing as the decriminalization of selfhood. Selfhood2 is the sense of identity created based on the connections and relationships we have with other people, human ideals and morals, and experiences. It’s widely known at this point that our circumstances play a large role in constructing our identity, and that our circumstances are ruled by institutionalized social relations and power dynamics. It’s time to remember that such relational dynamics only exist as long as we, as a society, allow them to.

The language of our discourse must be inclusive of differences if we hope to deepen our understanding and broaden our practices of humanity. These differences, however, must be used to our advantage as a cumulative measure, not a reductive one, to reclaim our agency and humanity. Rather than defining our identities through contrast with those who seem different from us, we must work to find ourselves in a common pursuit of unveiling and challenging the injustices that, in one way or another, affect us all.

Edited by Catharina O’Donnell

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Global Transformations: Anthropology and the Modern World. Palgrave MacMillan, 2003.

- Leendhart, Maurice. “The Structure of a Person,” in Do Kamo: Person and Myth in the Melanesian World. Translated by Basia Miller Gulati with a preface by Vincent Crepanzano, Chicago University Press, 1979; Rose, Nikolas. Inventing Ourselves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood. Cambridge University Press, 1998.