Population Ageing and the Refugee Crisis

Today, the majority of the developed world is facing the economic consequences of an ageing population and a shrinking workforce. This is the result of lower fertility rates, the ageing baby boomer generation, and increased life expectancy. Now many governments are looking for potential policy solutions to prevent the negative effects of a disproportionately older population. Because immigration has generally been shown to be beneficial for the economy, many governments are looking at generous policies to boost the labour force. Unfortunately, the current economy compounded with Europe’s refugee crisis has resulted in the rise of the extreme right and opposition to many programs that could moderate population ageing.

The European Union (EU) faces this issue at a nebulous time, with refugees from the Middle East and Northern Africa flowing through southern European states into the Union. Many proposed policies to aid the shrinking labour market involve some reform of immigration policy, so it may seem that these two crisis have the potential to come together to resolve each other. But neither issue is as straightforward as it might seem, especially considering the integration issues of the EU’s labour market. Immigrants to the EU face language barriers, cultural divides, and a potentially inaccessible job market. To understand how they influence each other, there are key mitigating factors that must be addressed to find concrete and stable solutions. The interconnected nature of immigration issues and the free flow of labour within the EU means that these problems need to be handled as a coordinated effort.

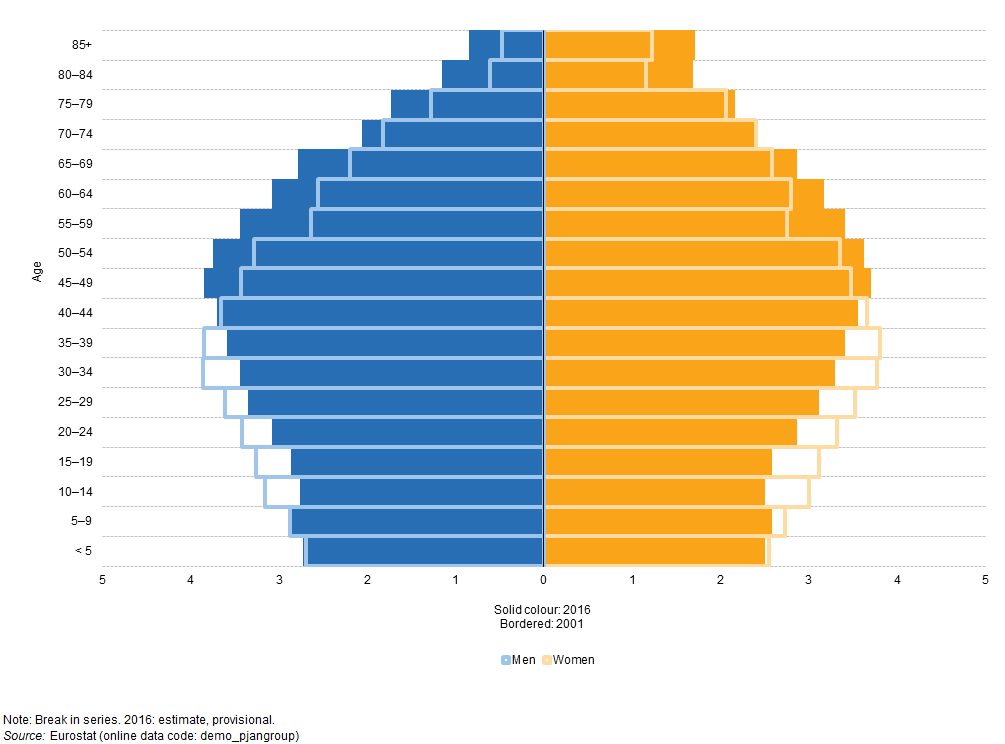

First, there are three main factors causing the shifting population demographics. More women entering the workforce and better access to contraceptives have resulted in falling fertility rates. People are living longer after retirement and are more likely to retire early, resulting in added strain to pension plans at the same time that fewer workers are contributing. These factors are combined with natural ageing of the post-war baby boomer generation to create an incredibly lopsided population distribution.

In order to combat this, the underlying factors must be addressed. This means encouraging later retirement, developing parental leave programs that make it easier for women to balance work and pregnancy, and otherwise supplementing the workforce. Immigrants provide a potential solution; however, there are complex dynamic relations governing the immigrant groups of Europe which mean that no country can tackle this issue alone.

There are several distinct groups of migrants within the EU that all pose different benefits and complications for the economy. There are immigrants, sometimes temporary, coming from within the EU itself – typically from East to West or South to North. There are also increasingly large numbers of asylum seekers, and economic migrants, coming from the Middle East or North Africa, as well as other immigrants from outside the EU. In the case of those coming from one EU country to another, immigration that may be beneficial to the receiving country might actually be damaging to the prospects of the country of origin due to the loss of skilled labourers. For example, Western Europe has largely benefited from immigrants coming for the South and East, while exacerbating the ageing population crisis in those countries. Additionally, the loss of both high and low skilled labourers slows the development of the economy as a whole. Consequently, the EU must take coordinated action in dealing with population ageing, so as to treat it as a whole.

Both population ageing and the refugee crisis have different effects across the EU. Many displaced people end up at first in South or Eastern Europe, like Greece for example. For the most part, these countries are ill-equipped to handle such large amounts of people and asylum seekers are left in limbo for extended periods of time. In order to combat this disproportionate burden, the EU set out resettlement requirements for refugees for each country, however certain countries, such as Hungary and Poland, have refused to fulfill these resettlement requirements. These resettlement programs are vital to economic and population stability in the EU as a whole and in the lives of individual refugees. High-skilled and low-skilled refugees could do much to boost the economy of the EU, if given effective and legal resettlement programs that allow them to integrate and access fully European society.

Many current immigration programs target high-skilled workers living outside the EU, however these immigrants are nowhere near enough to affect population distributions. Additionally, much like within the EU, drawing in high-skilled foreign immigrants can have negative effects for their country of origin, potentially contributing to the global issue of “brain drain” in developing countries.

If immigration were to be the sole solution to population ageing, the EU would need to take in more than 1 million immigrants every year. While this nears the number of asylum seekers in 2015, it is not a true solution, as refugees can be children and older adults, and often require government support when immigrating into new communities.

Furthermore, unstable economic conditions coupled with an increase in immigrants have resulted in the rise of right-wing nationalism targeting refugees for what they see as taking their jobs and adding strain to social welfare systems. This social climate in Europe makes it increasingly difficult for refugees and other immigrants. In general, immigrant communities tend to have higher rates of unemployment and less job security. This may be for numerous reasons: language barriers, discrimination, or lack of access to the job market. Nevertheless, many right-wing groups see immigrants as a threat to their jobs and livelihoods, making generous immigrations programs unpopular at this time. In reality, not only will these programs not fully address immigration issues but they are politically controversial and therefore difficult to implement.

In conclusion, neither population ageing nor the refugee crisis can be solved simply, but both require a coordinated effort on the part of the EU to avoid merely redistributing crises from country to country. There are a variety of solutions in population ageing, including later retirement, higher taxes, and encouraging unpaid work post retirement. Regardless of the policies chosen, the EU needs to overcome rising nationalism to effectively handle these issues.

Edited by Zoë Wilkins