Protesting on Parc: Montreal’s Friday for Future

It's one thing to watch a crowd move down a street, but it's another thing to be in it. It's like being pulled by a current—it's hard to move against it or exit, and even harder to stop in the middle of it.

Protesters gather at the George-Étienne Cartier Monument before the start of the march. Photo by Iman Zarrinkoub.

Protesters gather at the George-Étienne Cartier Monument before the start of the march. Photo by Iman Zarrinkoub.

Arriving at McGill Friday morning, the buzz in the air was tangible. Students were milling around with posters under their arms in lieu of books, ready to protest, but waiting to start. Nobody wants to be the first one at a party—let alone the first one yelling in the streets.

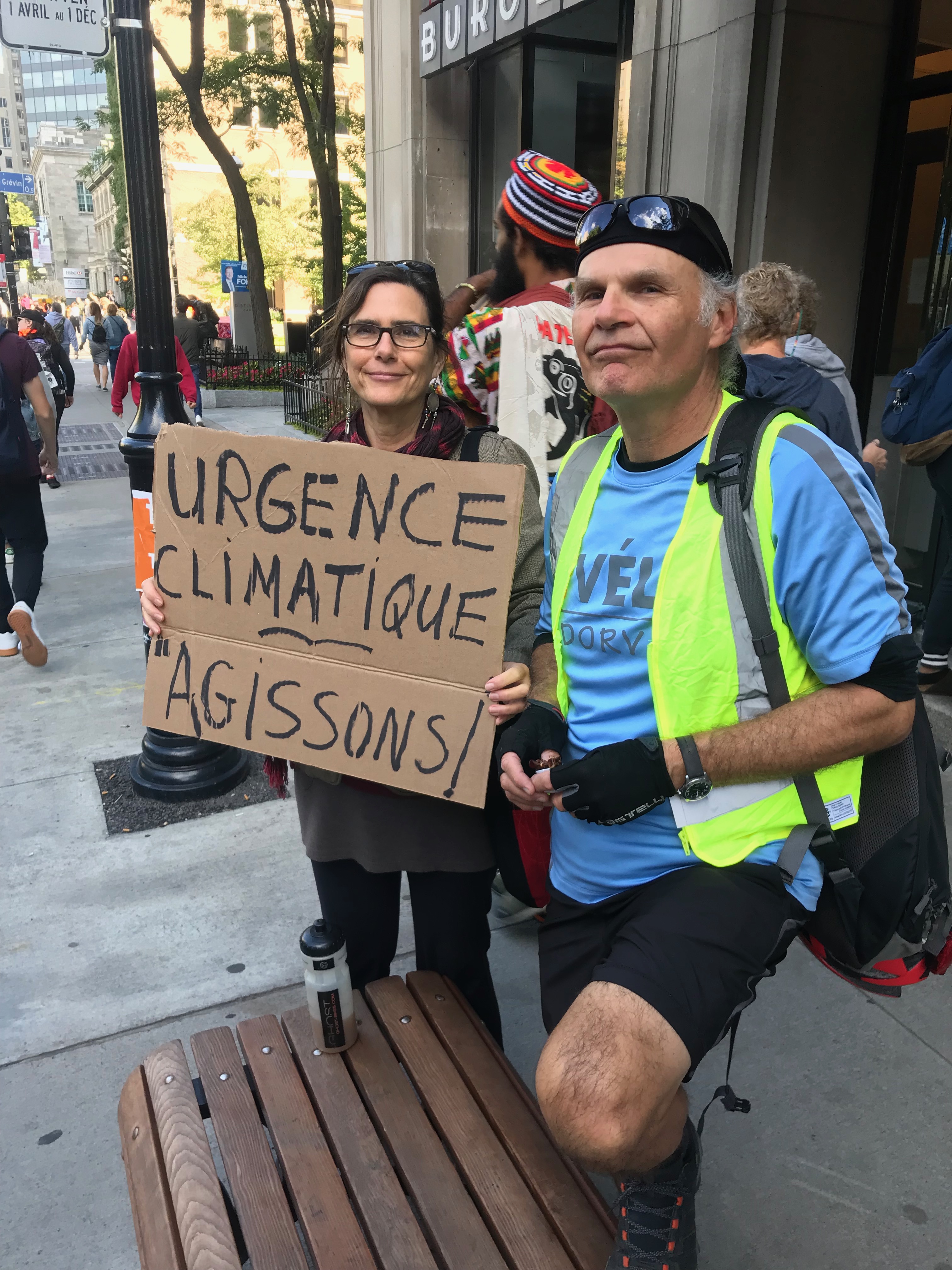

Killing time, sitting on benches until the event kicked-off, I asked a few students what brought them out. Their expressions made it seem as if it was a dumb question. One student said to me: “Same reason everybody else is. I’m angry. The older generation isn’t doing anything. I’m just pissed.” Another told me that although we live in a democracy, the economy is practically a dictatorship: “We’re living in a crisis but the government isn’t acting like it.” He went on didactically, saying that shareholders and board members have disproportionate power and that they only want to see growth. He asked me if I had ever read Marx. I said yes. He invited me to join a reading group.

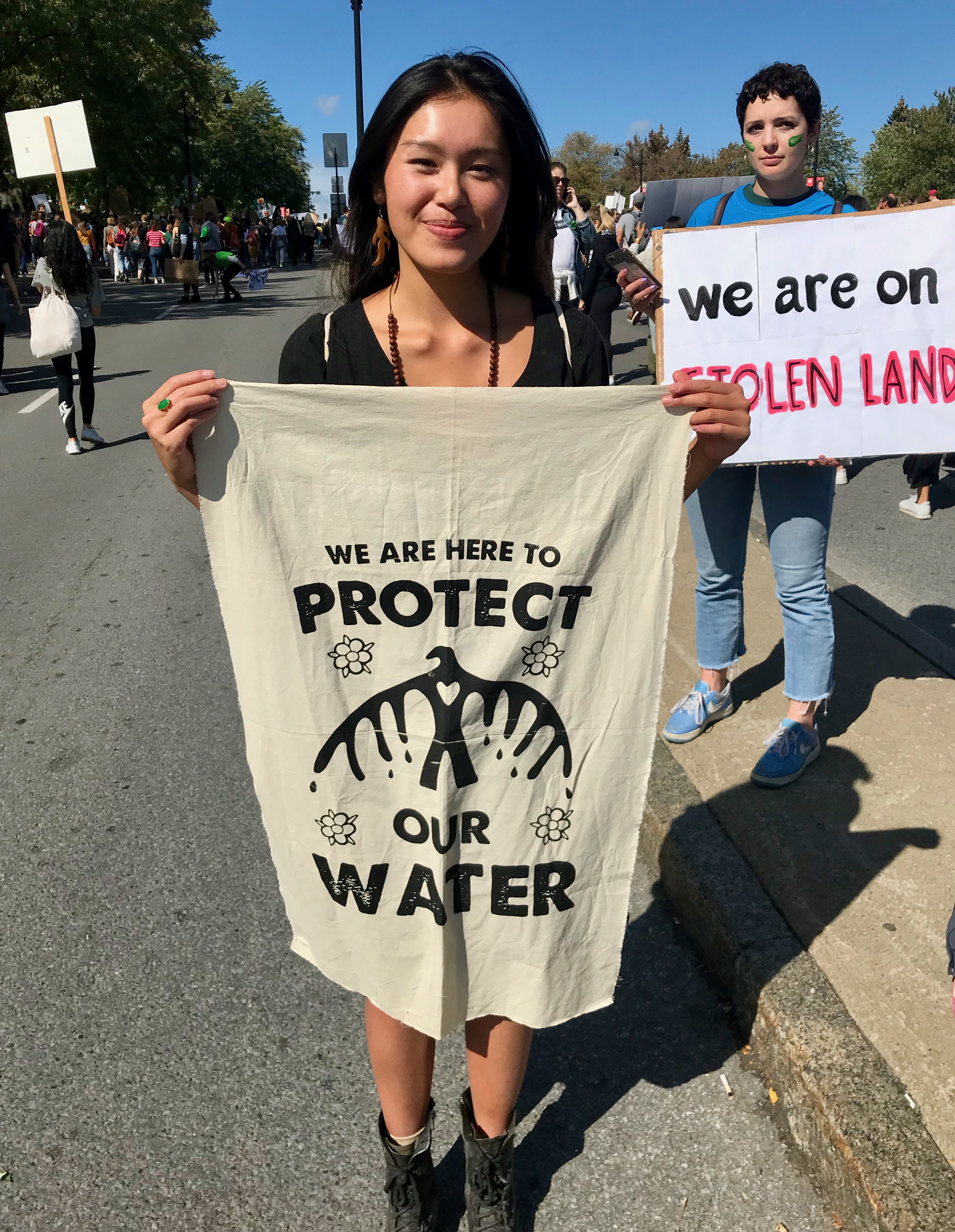

McGill students gathered on McTavish to hear several speeches prior to heading to the Sir George-Étienne Cartier statue on Parc. Jacqueline Lee-Tam, McGill student and climate justice organizer, spoke into the megaphone: “Number one: Brown, Black, Asian, and Indigenous people have been on the frontlines of climate change for generations… Number two: Climate justice means LAND BACK… Number three: We will win with EVERYONE or we won’t win at all.” Her speech had something for everybody. There were moments of loud energy when the crowd cheered and followed her cue to chant, and there were reflective moments thanks to moving imagery: “One day when I’m a mother I want to look my daughter in the eyes and tell her how we won.”

English Professor Derek Nystrom, who recently resigned from the McGill Board of Governors as a protest against fossil fuels, also spoke on McTavish. He lamented that Board Members never failed to say how much they loved students who came to argue for divestment—his colleagues always remarked that they were so smart, and so passionate. Yet, Nystrom said that they also never failed to vote against them. He pleaded: “You say they give you hope? Well, what are you gonna do with that hope?” shedding light on the fact that it is all too easy to voice the feeling of being inspired, and rare to see people act on it. And with that in mind, the march towards Sherbrooke began.

It’s one thing to watch a crowd move down a street, but it’s another thing to be in it. It’s like being pulled by a current—it’s hard to move against it or exit, and even harder to stop in the middle.

Eventually, I navigated my way out and saw a couple of construction workers sitting with their lunches across from the Roddick Gates, watching the march go by. I asked them what they thought. They replied: “We’re working. You can march, you can not march. But it’s the climate. I don’t see what it’s going to do.” They didn’t want their photo taken. I kept thinking about them throughout the day. There is no doubt that the climate movement brings together people of all generation, classes, and colours, but there is also no doubt that there are limits to the inclusiveness. One participant tweeted about racial tensions within the protest: “Despite the fact the front of the march was supposedly a space for Indigenous peoples, white people were aggressively trying to push past the entire time. Many became defensive or violent when reminded to respect Indigenous space.”

In the most packed part of the mass, I saw moms doling out crackers to their kids next to a group of women singing in Spanish and a band with a Seussophone. In the middle of Parc, in front of the statue, I came by an elderly lady with a walker who seemed to be alone. I then noticed that in the basket of her walker, she was carrying her cat. I struggled to get through the people next to me, and she smiled to me and nodded down to her apparatus, laughing: “People tend to get out of my way!”

Once I arrived at the statue on Parc, it was obvious that many thousands had already been there for hours, once again, waiting. Nobody was marching. In fact, people were hardly moving. Every once in a while, a group yelled into the air, moved by the spirit of the day. It struck me that while the magnitude of what we were up against was obvious, there was also something undeniably fun about being out there. For a couple of hours, there was no unified chanting, no speeches, no movement; eventually people got lazy with their posters and rested them on the ground. We were waiting to march to hear Greta’s speech downtown, but the time spent standing on Parc on one of Montreal’s busiest roads wasn’t unimportant—there was a special, if imperfect, sense of solidarity in standing around together.

People didn’t come out to debate climate policy. Most students on McTavish probably couldn’t hear the speeches through the megaphone, because they were either too far away or because the noise was blurred out by the crowd’s cheers. Greta’s speech wasn’t about policy programs: it was about the power of unity behind a common cause, and how our actions were changing the world by challenging the empty words of bureaucrats. Once Greta’s speech ended, the crowd filtered out much like they do at the end of a concert. Gradually, roads that had been blocked off were slowly reopened to cars.

I think it’s true that it’s really hard to talk policy when you’re doing political action—and that’s ok. In an ideal world, the march energizes participants and encourages them to mobilize further, while politicians let both the real and symbolic weight of the turnout influence their platforms for the upcoming federal election. Justin Trudeau and Elizabeth May were both in attendance in Montreal, while Jagmeet Singh opted to march in Victoria. One participant was arrested after attempting to egg Trudeau, whose controversial climate record includes support for pipeline expansion projects and an unpopular carbon tax plan. Indeed, when Trudeau spoke with Thunberg the morning of the march, she said he wasn’t doing enough. Andrew Scheer, whose climate program is unique in that it relies predominantly on new technology, did not attend any march across the country. A rally of his was interrupted by climate protesters on Saturday in Saskatoon.

Although the annual march lasted only a few hours, the movement continues. Dozens of groups were in attendance trying to get people on board for sustained engagement. Several McGill speeches brought attention to Divest McGill, who continue to meet frequently to put pressure on McGill’s Board of Governors and are hosting an information session on campus October 4th. Greenpeace is meeting at the Sir George-Étienne Cartier statue October 5th, where they’ll join up for a mass mural event. Then, there are organizations like Our Time, who are advocating for a Green New Deal and have a strong Montreal chapter. Few movements have successfully mobilized so many, but there is reason to be optimistic about climate activism in Montreal and nationwide: numbers collected by Fridays for Future Canada assert that Montreal’s march of 500,000 was by far the largest in the country, constituting half of Canada’s estimated 1 million participants. Further, of all the strikes across the globe, the organization asserts that nearly one out of every six participants was Canadian.

We know that the effects of climate change will be felt in unpredictable and increasingly brutal ways, and we know that those who are least responsible for causing pollution will suffer disproportionately. We do not know what the future of climate policy will look like, either in Canada or globally—which is why more action is needed to guarantee our future. The magnitude and energy of the afternoon’s march was noteworthy, and it was at times reminiscent of a party or a concert—but don’t be fooled. This is politics, and there is more work to be done.

Edited by Chanel MacDiarmid