Proxy Crisis? India and China Compete in Sri Lanka

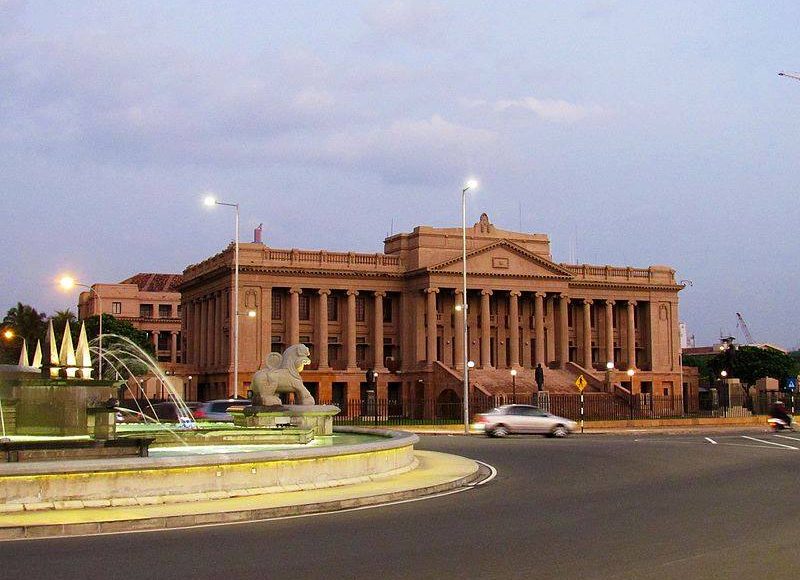

The Sri Lankan Parliament. https://tinyurl.com/y8sxkthl

The Sri Lankan Parliament. https://tinyurl.com/y8sxkthl

When the dust kicked up by this constitutional crisis settles, the new government will likely have capitalized on the threat – or promise – of Indian or Chinese influence.

On October 26th, the Sri Lankan president Maithripala Sirisena threw the country into a constitutional crisis when he fired the Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, and withdrew his party, the United People’s Freedom Party (UPFA) from the ruling coalition. In short order, President Sirisena swore in a replacement, and suspended parliament.

Constitutional Crisis

The Sri Lankan constitution does not allow President Sirisena to dismiss a Prime Minister. His dismissal of Wickremesinghe was unconstitutional.

In Sri Lanka’s presidential republican system, the president is endowed with significant political power. The president is both the chief of state and head of government; this means that he appoints the prime minister, who is approved by parliament and chooses a cabinet in conjunction with the prime minister. The president is within his rights to “prorogue” or end the current session of parliament. However, an amendment to the constitution overseen by Mr. Sirisena himself shortly after he took power in 2015 disallow him from replacing the prime minister unless he dies, resigns, or receives a vote of no confidence from parliament.

Mr. Wickremesinghe is alive and well, and as of publishing, remains ensconced at Temple Trees, the Prime Minister’s official residence.

With a Throwback

A constitutional crisis is already cause for concern, but the move was further complicated by President Sirisena’s choice of replacement: Mahinda Rajapaksa, two-term president of Sri Lanka and formerly President Sirisena’s party leader. Former president Rajapaksa was defeated before a third term in 2015 when Sirisena abandoned him to form a coalition with PM Wickremesinghe.

President Rajapaksa’s flagrancies in office included ballooning national debt, passing a constitutional amendment allowing unlimited presidential terms, and disappearing journalists. However, the most damning were the alleged human rights abuses overseen by Rajapaksa during the final military offensive that ended the 26-year-long civil war between the minority Muslim LTTE (Tamil Tigers) and the majority Buddhist government forces. International condemnation accelerated a distancing between Rajapaksa’s government and West, and the strengthening of Sri Lanka’s ties with China.

In 2015, Sirisena and Wickremesinghe campaigned on a promise of presidential accountability, and within four months of their election passed constitutional amendments limiting presidential power. They have worked to correct a democracy on the path toward authoritarianism and bolstered an economy drowning in debt.

Now, three years into their five-year term, their coalition government has dissolved. The Economisttheorizes that Sirisena anticipates Rajapaksa will be appointed Prime Minister once his party sweeps parliamentary elections in 2020. This prediction suggests Sirisena has chosen to move now before “he has little to offer the likely future prime minister.”

However, international observers have speculated that the political turmoil can be broken down along pro-India and pro-Chinese lines.

Back and Forth Across the Bay

India has long been a prominent foreign partner and external influence on the politics of Sri Lanka. The proximity of the countries has produced what the High Commission of India in Colombo describes on their website as “political understanding, a historic past, geographic realities and socio-cultural empathy”. India is Sri Lanka’s biggest trading partner, with bilateral trade valuing a reported $4.7 billion in 2015. India’s approach to the relationship has seemed benevolent in the past, as in the case of the Indian Ocean tsunami. India responded with near-immediate humanitarian military aid despite coping with the effects of the tsunami on her own shores.

However, India’s presence in Sri Lanka has not always been so friendly. A peacekeeping force sent to oversee a ceasefire between the Sri Lankan government and the Tamil Tigers in 1987 was never welcomed by the Rajapaksa government. It was understood by that administration as an infringement on Sri Lankan sovereignty. Relations with Tamil separatists soon disintegrated into guerrilla warfare that led to alleged human rights abuses by the Indian Peacekeeping Forces.

In the early 2010s India joined major Western powers in a vote by the UN Human Rights Council urging investigations into alleged war crimes committed by government forces during the end of the Sri Lankan civil war. In 2010 Rajapaksa was eager to develop a fishing village called Hambantota and sought investment from India, who declined. China stepped in and funded the construction of the port when the Western establishment, and India with it, turned its back on Rajapaksa. To date, China has invested over 15 billion in Sri Lanka – 11.18 billion of that under Rajapaksa’s rule. In 2017, when the Hambantota port proved unprofitable, China won control of the port in a 99-year lease from Sirisena’s government.

The acquisition of control over the port fits neatly into China’s apparent plan for the region. Hambantota joins ports jointly-owned or developed from Hong Kong to Djibouti as part of China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. China’s non-interventionist reputation and free-flowing capital have made it increasingly popular in the region. Smaller nations like the Maldives, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka have long sought a regional alternative to over-bearing India, and Chinese investments provide just such an alternative with the perk of massive development projects.

However, Rajapaksa’s close relationship with China in 2015 was also plagued by an $8 billion debt. Other countries that received investments from China have faced similar consequences. Under Sirisena this debt has been reduced by ceding assets to China, of which Hambantota port was one. The dilemma has also made Sri Lankans more open to India’s attempts to play catch up on the island.

After China won control of Hambantota port, India initiated talks with the Sirisena government on the possibility of developing Trincomalee port into a naval and commercial base. Several airport construction projects to be assisted by India are pending, including one close to Hambantota. In October, Sri Lanka cancelled a housing deal with a Chinese company worth $300 million US and awarded it to an Indian company.

Playing the In-Between Game

Does Rajapaksa’s return spell an end to this shift toward Indian partnership? The answer isn’t so simple; the fact remains that Sri Lanka is not divided into simple pro-India and pro-China factions. Rajapaksa has rebuilt his personal relationship with New Delhi in the last three years, visiting just last September. Meanwhile, Sirisena, who has overseen the recent warming of relations with India, made the claim in a cabinet meeting that the Indian intelligence agency Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) is trying to ‘kill’ him–demonstrating his disapproval of their relationship. Rajapaksa similarly credited RAW with his 2015 loss in the presidential election.

Several articles have noted the Chinese envoy to Sri Lanka was the first to visit Rajapaksa to congratulate him on his new – unconstitutional – appointment on October 27th. However, the same ambassador also visited Wickremesinghe that evening at his official residence.

The dominant strategy of both the supposed ‘pro-India’ and ‘pro-China’ leaders seems to be reaching across the Indian ocean and engaging with both India and China. Such a strategy seems entirely reasonable given the competition has resulted in massive foreign direct investment in the small island nation. When the dust kicked up by this constitutional crisis settles, the new government will likely have capitalized on the threat – or promise – of Indian or Chinese influence. In either scenario, it seems likely that the Sri Lankan government will continue with their fluid foreign policy. That’s just life between two super powers.

Edited by Helena Martin