Responses to Rhetoric: Brexit and the Rise of Hate Crime in the UK

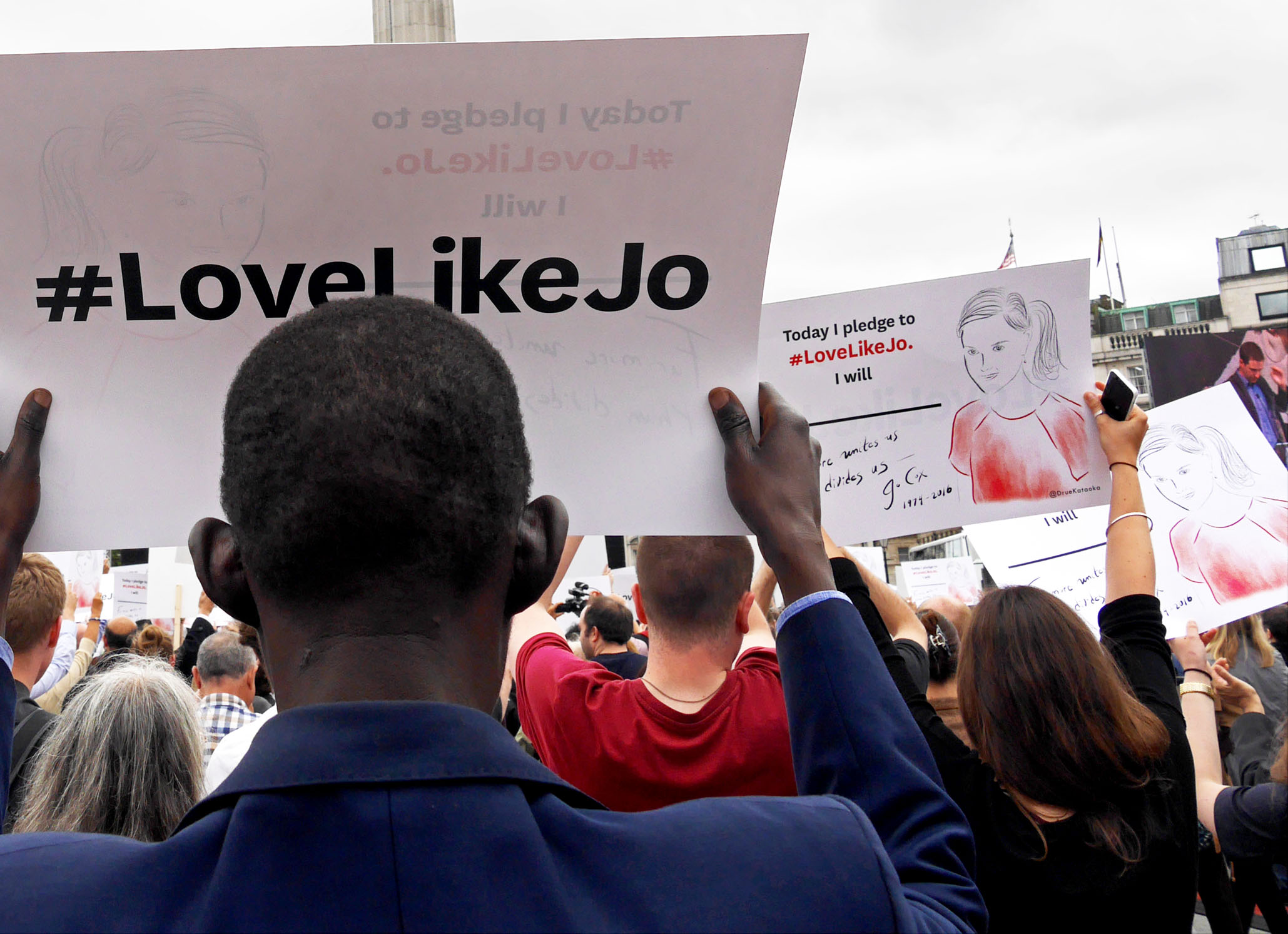

Remembering Jo Cox - Trafalgar Square

https://flic.kr/p/JniaBf

Remembering Jo Cox - Trafalgar Square

https://flic.kr/p/JniaBf

Warning: this piece will reference racism, rape, and general violence.

What is it about fear in politics that is so powerful? So prevailing? So potent? Its pervasiveness is derived from the appeal to fear, often times putting the control in the hands of politicians. This type of control is a driving force commonly seen throughout history. There is a misconception, however, that in a well-formed, modern, progressive, democratically-entrenched society, the use of fearmongering, scapegoating, and demagoguery is archaic and far-gone – something only to be exploited by the likes of dictators in the developing world. This, of course, is wholly untrue, what with a resurgence of aggressive nationalism including rampant “Trump-ism” in the United States, Marie Le Pen’s plans for French policy, some of Harper’s proposals for women in Canada, and, most notably, the Brexit referendum. The dangerous nativist rhetoric in the UK in the time leading up to the referendum has caused severe backlash in the weeks and months post-Brexit, including an undeniable rise in hate crimes.

There had been rising tensions in the UK ever since the referendum announcement. The polarizing decision created an uncertain and discontent atmosphere throughout the country. Then Jo Cox was murdered in West Yorkshire. Her widow, Brendan Cox, in a New York Times op-ed piece stated plainly, “members of parliament don’t get murdered in Britain”, describing well the gravity and shock of what seemed an implausible act for the ‘progressive’ UK. He went on with the telling remark: “history shows how quickly hatred is normalized”. It is crucial to distinguish whether a country (like the UK) has managed to progress past social prejudices or has simply suppressed and internalized them.

https://flic.kr/p/JniaBf

An insight team working in London showed a 16% increase in hate crime in the past 12 months leading up to August 2016. It also showed that in the 38 days after the referendum there were more than 2,300 recorded race-hate offences – Eastern Europeans were particularly targeted. Although there has been some negligible controversy as to whether the atmosphere is actually hostile, (the Daily Mail has said that certain people with jobs in statistical analysis often owe their jobs, status and mortgages to the “fashionable perception that hate crime is somehow spiraling out of control”), the day-to-day news shows an anti-foreigner and racist sentiment in the UK that is certainly in large part, if not, totally responsible for these crimes. In Gloucester, a white man began yelling in a supermarket queue, “This is England now, foreigners have 48 hours to f**k right off. Who is foreign here? Anyone foreign?”. There was an English Defence League gathering outside a mosque in Birmingham with a flag that read: “Rapefugees Not Welcome”, as they shouted “Allah, Allah, who the f**k is Allah?”. There is a consistent slew of racist graffiti, as well as cards found in postboxes reading “No more Polish vermin”. This general mood has been the foundation for cases of extremism. There have been many reports from the British Transport Police (BTP) that detail dozens of cases of aggressive racist and anti-religious comments to the staff, some resulting in bodily harm. Six teenage boys were recently arrested in Essex after an Eastern European immigrant was killed in a brutal street attack after he was heard speaking Polish.

Rose Simkins, the chief executive of charity Stop Hate UK, said: “While we are encouraged that people have found confidence to report incidents due to the national publicity on the issue, it is a sad fact that the numbers of all hate incidents are extremely under-reported”. Victims often do not report incidents because of a lack of confidence in the authorities who deal with these issues. There is also significant gap between reported cases and effective prosecution, as a result, a large number of racist hate crimes seem to go unpunished.

A lack of confidence in local authorities reflects the criticism there should be for the more notable political leaders spearheading the referendum. The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has said that prominent politicians should share the blame for the outbreak of xenophobia and intimidation against ethnic minorities. Boris Johnson, who fronted the “Leave” campaign has said, “Napoleon and Hitler tried to dominate the continent. The EU is an attempt to do this by different methods”. Nigel Farage supported a “Breaking Point” poster, that portrays a queue of refugees with the slogan “Breaking point: the EU has failed us all”. Farage also held a speech where he declares, “I believe this Thursday can be our country’s independence day!”. (John Oliver makes the important point that not only was the UK already independent, but it is, in fact, a country that many other countries celebrate their independence from).

The campaigns of conservative leaders in Britain effectively gave a “green light” for racial, religious and generally hateful kinds of discrimination. Not only did they fail to condemn it, but more destructively, their attitudes emboldened individuals to carry out acts of hate.

Many may, not without cause, blame the traditional, conservative individual who has a strong dislike for change and the globalizing world for much of the hate speech and crime. An informed electorate is what creates a reasoned democratic, government. To examine the political atmosphere, however, is to identify the origins of this hate. There is a circular aspect to this problem: politicians can easily ‘plant a seed’ of hatred, as the individual derives authority from the leader’s ethos, which translates into political support. There is a built incentive to instigate the fears of the electorate in the midst of a vote or election, as politicians have not only the power of persuasion, but the power of political legitimacy. We must hold the leaders like Johnson, Farage, Gove, May, etc., responsible for having lent credibility to the hostile nativism that had such drastic social consequences. Ironically, many “pro-leavers” have taken a large step back post-Brexit, potentially apprehensive about the decision they so rigorously pushed for.

The ‘Euro-sceptics’ in the UK are not necessarily to blame for making their choice to “leave”, but rather for grounding that choice in fear: a fear of lack of economic control, a fear of anti-nationalism, a fear of other people. The social consequences of Brexit cannot be ignored as the ‘leave’ campaigns are still having major effects on the continuing environment. Just as imperative as stopping the vicious post-Brexit crimes and ensuring the prejudice notions and behavior are not normalized, is acknowledging the faults and holding responsible the powerful campaigners who influenced it.