Rushed Elections and Ignored Questions: The Paris Summit on Libya

On May 29th 2018, the Elysée welcomed what French President Emmanuel Macron called a “historic event” gathering all of the parties involved in the ongoing conflict over authority in Libya. For the first time, the four main entities fighting for power in the country since former dictator Muammar Gaddafi’s overthrow in 2011 gathered and recognized each other’s existence and significance in Libya. Moreover, the regional countries involved in Libya were invited to the Summit , in particular the UAE, Russia, Qatar which have been supporting Haftar and more generally the Tobruk-based government, and Turkey which has had an ambiguous role by supporting the Islamist-dominated General National Congress. The UNSC P5 countries, the African Union, the EU, and the Arab League were invited as well.

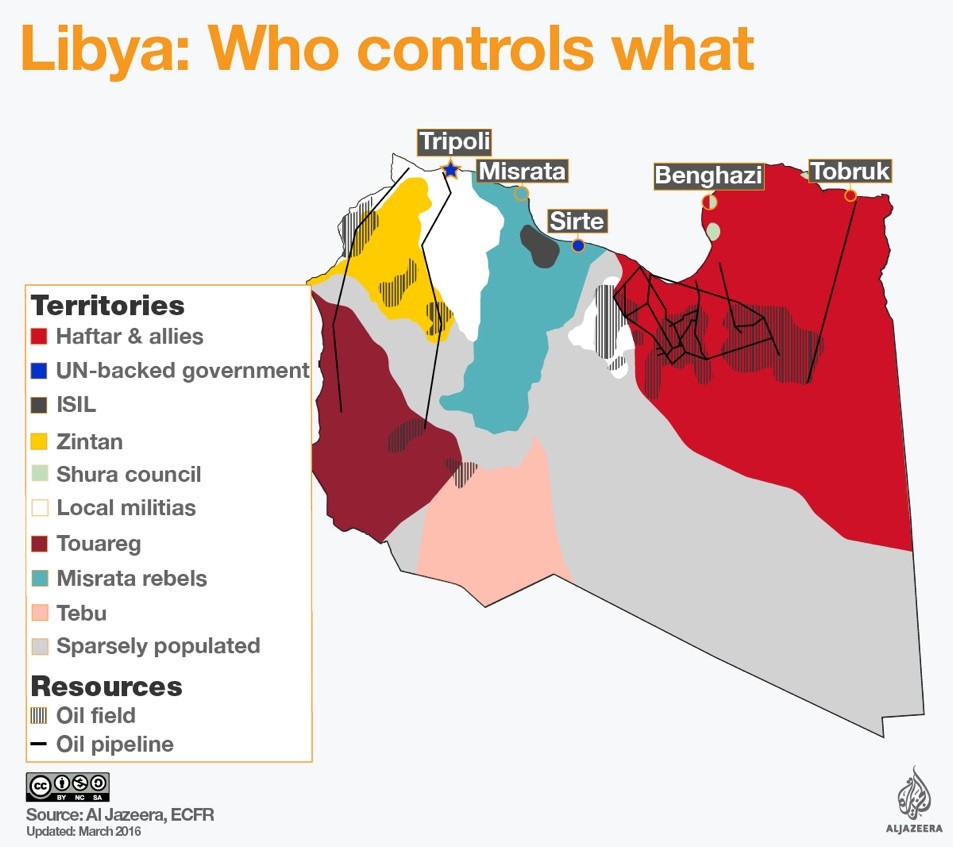

The situation in Libya has shifted numerous times since 2011. Today, the country is controlled in Tripoli by Fayez Al-Sarraj, the UN-backed Prime Minister since 2016, and in Tobruk by the head of the Libyan National Army (LNA), the Marechal Khalifa Haftar. By instigating its own Central Bank and Parliament, Haftar challenges Al-Sarraj by not recognizing his government and by gathering the support of regional powers such as Egypt, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. These countries have been prioritizing the military strength of Libya, represented by Haftar, in the fight against ISIS and terrorism in general. For the same reason, France has been more lenient towards Haftar’s parallel power. To a certain extent, all of these countries have economic interests in supporting Haftar, who is also in control of most of the Libyan “Oil Crescent”.

Along with Al-Sarraj and Haftar, two other prominent figures in the Libyan political landscape were present at the Summit: Aghela Saleh, Speaker of the House of Representatives of Tobruk, and Khaled Mishri, the head of the High State Council based in Tripoli.

Hosted by Macron, the Summit aimed to reach an agreement between the four delegations represented to hold presidential and legislative elections on December 10th, 2018. An ambitious goal for Macron, especially after the failures of the Skhirat agreement in 2015 and the superficial meeting held between Al-Sarrah and Haftar last summer in Paris. However, this agreement seems to be yet another incomplete attempt to address a complex situation – one that mere elections won’t be able to fix.

First, one could ask whether or not elections should be the top priority for the country. While Macron displayed a father-like pride in the Summit’s achievements, Sarraj acknowledged, during the press conference which followed, that the ongoing violence, the active presence of ISIS near Sirte, the abysmal human-rights situation and the refugee crisis were all challenges that the fragile agreement will have to account for in its realisation.

Indeed, finding a consensus in Libya, as tenuous as it is, is a considerable step. But the protracted nature of the internal conflict first requires a commitment to end violence. If such commitment seems largely assumed by Macron, Sarraj and UN Special Representative Ghassan Salamé in their post-Summit press conference, nothing is less certain. None of the actors signed the agreement, which demonstrates the need for each leader to consult with its clan to decide on which strategy to adopt, and whether or not to upkeep their status as a parallel power or to join mainstream politics.

Moreover, the Paris agreement stipulates that the parties must both agree on how to frame the electoral procedure – either by reforming the 2011 Interim Constitutional Declaration or by passing an electoral law – and actually implement this collective decision as a bedrock for the elections before September 16th, 2018 so that elections could be held on December 10th. Once again, if Macron seemed confident that this set-calendar will incentivize all parties into coordination, this assumption is premature if accounting for the recent ISIS-led attacks on the electoral commission in Tripoli on May 2nd.

Even if the international and regional powers economically involved in Libya – namely Russia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates – have approved of the content of the agreement, only time will tell if this approval will result in de facto support of the agreement in the coming months. These countries have been economically, militarily, and politically supporting Haftar’s LNA in spite of the existence of a UN-backed government in Tripoli: their influence on Haftar will be a crucial determinant of the success of the Paris agreement. The focus on the Syrian war and the lack of media attention on the Libyan question are leaving a lot of wiggle room for these countries to stray from what was said in Paris, and add yet another question regarding what is at best an ambitious and at worst an unrealistic and aggravating agreement.

Concentrating diplomatic efforts on a multilateral agreement to stop resorting to violence between all parties would be as ambitious is what the Paris agreement promises. However, it would be a more realistic assessment of today’s Libya. Such an agreement should not only include Haftar’s LNA, but involve delegations from the different Libyan tribes and from ISIS itself. While these actors do not pretend to be willing to run in elections, not inviting them at the Paris Summit is ignoring part of the problem.

For Macron and Salamé, making disarmament a priority would mean acknowledging the still chaotic situation in Libya. Yet, no election can fix endemic resort to violence nor can it guarantee the feasibility of the establishment of civilian rule, especially when one of the most important Libyan stakeholder is a military leader. Indeed, ISIS is very unlikely to engage in such commitment to end violence: however, uniting the rest of Libyan actors behind peaceful settlement of the ongoing conflicts in the country would build a foundation upon which elections could be held, and create a precedent for how Libya shall deal with internal dissent from there on.

There is much more that Libya has to face before even thinking of holding elections. The Paris Summit appears as an attempt for Macron to strengthen his thus far mitigated position in international politics, particularly in the fight against terrorism. Yes, uniting everyone in Libya is the first step to fight ISIS. No, it’s not the most urgent problem in the country, nor is it the best first step to address it. Elections will be useful when every stakeholder will put down its weapons. Yet, elitist diplomatic agreements look better on camera than people giving up arms, and are easier to reach than actual commitment to peace. While Salamé mentioned a growing popular will to hold elections, selling dreams of peace to people with elections is at best naive, and at worst dishonest. As an attempt to escape from a protracted deadlock, and as it clearly allowed some diplomatic progress through recognition and dialogue, the Paris Summit’s process has been more useful than its result will probably prove itself.

Edited by Sarie Khalid