Selling the Iraq War

071129-N-0696M-280

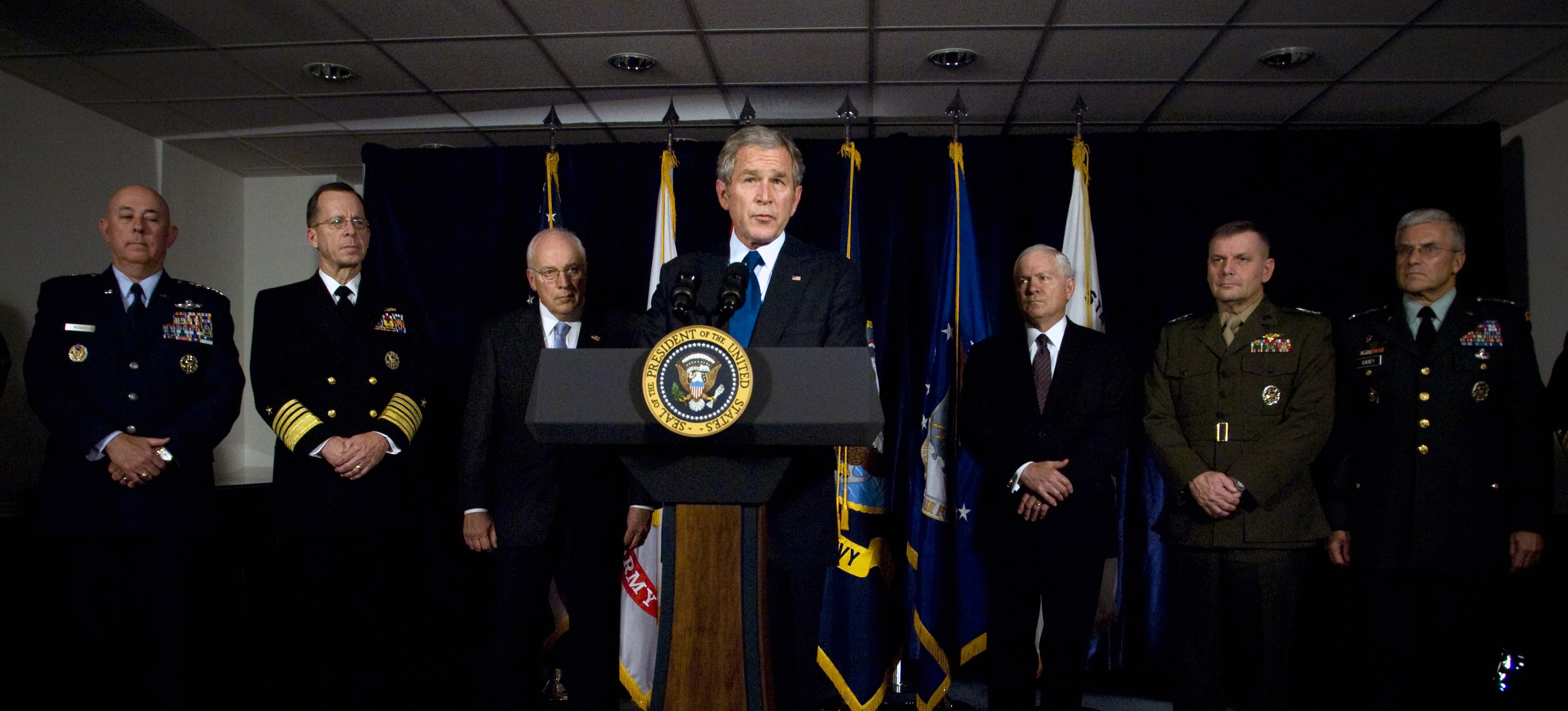

WASHINGTON (Nov. 29, 2007) President George W. Bush addresses the media at the Pentagon after a meeting with senior leaders discussing long-term strategic plans for the military. Bush met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates and Deputy Secretary of Defense Gordon England during the meeting. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Chad J. McNeeley (Released)

071129-N-0696M-280

WASHINGTON (Nov. 29, 2007) President George W. Bush addresses the media at the Pentagon after a meeting with senior leaders discussing long-term strategic plans for the military. Bush met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates and Deputy Secretary of Defense Gordon England during the meeting. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Chad J. McNeeley (Released)

March 20th 2018 marked the fifteenth anniversary of perhaps the most controversial and consequential armed conflict of the twenty-first century: the Iraq War. It has indeed been fifteen years since President George W. Bush announced on national television that American forces had begun “military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger.”

Of course, such language masqueraded a military endeavor that would claim nearly half a million lives, rack up a $2 trillion price tag, and result in untold costs for a country that remains in disarray. Major media outlets, like the New York Times, were careful to include editorials that acknowledged the war’s grim adolescence. CNN featured a piece that urged Americans to “not to repeat the mistakes of the past” in light of the destruction that the war has brought. Absent from much of these discussions was how the American media itself carried water for the war effort, and how political pundits and respected journalists served to legitimize and market the war to the American people. The media campaign that accompanied what would become an enormously unpopular war is crucial in understanding how this war, and other wars, are packaged and sold to populations.

Selling the Iraqi Threat

From the beginning, President Bush had viewed any proposal to invade Iraq as requiring a public relations campaign in order to persuade the American people that the war was necessary and just. In September of 2002, the Bush administration had planned to use the President’s 9/11 commemoration speech as an emotional lead-in to a speech he would deliver to the UN General Assembly the following day. The New York Times reported that administration officials hoped that Bush’s 9/11 remarks would “help move Americans toward support of action against Iraq,” which could come within six months. Bush’s chief of staff Andrew Card noted that the public relations campaign would need to begin in September because, “from a marketing point of view, you don’t introduce new products in August.”

The White House understood that it would not need its own state-media apparatus to force the bitter pill of war down the throats of the American people: the American news media was willing to act as this essential marketing conduit. On September 8, 2002, New York Times reporters Judith Miller and Michael R. Gordon penned an article quoting anonymous Bush administration officials who said that aluminium tubes were being shipped into Iraq as uranium-enriching centrifuge components consistent with administration claims that Iraq was in the process of acquiring weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). These reports ended up being false, as the aluminium tubes were used in the production of conventional rocket weaponry. Nonetheless, top administration officials such as Vice President Dick Cheney, National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice, Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld and Secretary of State Colin Powell used the story to push the false narrative that Saddam Hussein was indeed pursuing WMDs on NBC, CNN, CBS, and FOX Sunday morning news programs despite the fact that Miller and Gordon’s article used the Bush administration as its main source for the supposed intelligence.

On the whole, the US news media did not systematically challenge the Bush administration’s insistence that Iraq possessed WMDs, nor did it question reports that Hussein was pursuing nuclear weapons. When Colin Powell delivered a speech at the United Nations in February of 2003 falsely insisting that Saddam Hussein was hiding WMD facilities from UN inspectors, the US media reported Powell’s accounts as though they were true. As FAIR.org reported, journalists from major news outlets such as Andrea Mitchell of NBC, Dan Rather of CBS, and William Schneider of CNN, all uncritically reported Powell’s remarks as true.

Several more articles and reports did the work of selling the WMD falsehood to the American people, though they are too large in number to include here. Nevertheless, the media served as a crucial tool in legitimizing the Bush administration’s fever for war with Iraq by remaining uncritical of, and in many cases subservient to, the erroneous reports coming from the administration.

Embedded in the War

The Iraq War was hardly the first war to be subject to media spectacle, but it was one of the first to use the media as an integral part of the war effort. This process, known as “embedding,” involved “integrating journalists into military units for the duration of [the Iraq War].”[1] American Lieutenant Colonel Rick Long rationalized the process of embedding by explaining that “[the military’s] job is to win the war. Part of that is information warfare. So we are going to attempt to dominate the information environment.” There were anywhere between 570 and 750 embedded reporters in Iraq at any moment during the beginning of the war in March 2003.

Embedded journalists were indeed subject to a series of restrictive “ground rules” in which they agreed to have their articles reviewed by the American military prior to release, their movement restricted to their assigned military unit, and their embedded status liable to revocation at any point. One such regulation mandated that “Names, video, identifiable written/oral descriptions or identifiable photographs of wounded service members will not be released without service member’s prior written consent.” As such, journalists had to agree to restrictions on their coverage regarding the reporting of casualties in the Iraq War.

Embedding journalists had an effect on the kind of reporting that news outlets produced. While reporting was overwhelmingly factual,[2] the work of embedded journalists was more likely too biased from the perspective of the American troops with which these journalists were assigned. Embedded reporters identified with the members of their unit, and were more likely to produce positive or heroic stories about their experiences with the troops.[3] Additionally, news outlets depended on the live audiovisuals that embedded reports produced, but these reports did not tend to include the human cost of American military operations.[4] BBC correspondent Caroline Wyatt remarked that she felt like a “tool in the military toolbox” while embedded with British troops in Iraq. She likened the relationship with the soldiers to Stockholm syndrome, as she was being protected by her unit while reporting on their actions.

By contrast, journalists in the Arab media did not portray the war in the same way their American counterparts did. Hoda Abdel-Hamid, an Al Jazeera war correspondent and former ABC correspondent who reported on the Iraq War, noted the different approaches towards the war while working for both organizations. In an interview with NPR in 2008, Abdel-Hamid remarked that American coverage of the war was “more heroic,” as well as “more of a big show rather than what was shown on Arabic TV.” Abdel-Hamid explained that Al Jazeera, which reported extensively on the Iraq war several years after the initial invasion, sought to portray “some people’s misery, some death and destruction, some happiness and some anger.” Overall, Abdel-Hamid determined that “two completely different wars [had] reached these two organizations [ABC and Al Jazeera].”

Thus, the Pentagon didn’t need to completely control the kind of information that left the battlefield. By embedding reporters within the war effort, the resulting stories would reflect an American perspective, and create a journalistic kinship with the troops by whom they were being protected.

Image and Spectacle

War reporting, of course, is also a media product. What makes discussions about the US media “selling” the Iraq War to the American people so important is that Americans were not only buying a justification for a war, they were also buying a particular image of what that war looked like – an image mediated by television cameras and journalistic accounts and informed by ideas and sentiments about American military power.

An iconic example of this image-making comes from the April 2003 photograph of a group of Iraqis tearing down a large statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square, Baghdad. The image serves for many as a symbolic end to the Battle of Baghdad in the early weeks of the Iraq War, and an example of Iraqi jubilation at the toppling of their oppressive dictator. The reality of the demolition was rather different. Media outlets filmed and photographed the event by focusing on a small group of people – largely American Marines and journalists – around the statue, rather than depict Firdos Square as it was: mostly empty. In fact, the sledgehammer used for the toppling, as well as the American and Iraqi flags that were draped over the statue’s face were both supplied by American troops. Nonetheless, news editors largely demanded that the image of American triumph be telecast to the world. The war was far from over, but the image of Hussein’s demise served as an effective visual tool for the war’s marketing.

Image creation was not only done with visuals, but also with the language of the news media. News anchors, pundits and journalists were happy to recite George Bush’s doomsday claims of WMDs in Iraq but did not employ the same language to describe America’s armaments. TIME Magazine, for example, ran several stories in the early weeks before and after the war’s start that painted a spectacular portrait of the American war capability. TIME ran headlines like “Opening with a Bang,” and “High-Tech Brute Force” for stories that intricately described the features of the American military’s deadly arsenal.[5] Central to many of these descriptions was the notion that American military technology was so advanced it could largely avoid the civilian deaths normally involved in such a war. A TIME story reported that “if things went as planned, key civilian sites like bridges and power systems would largely be spared, bringing home the message that the U.S. target is Saddam, not the Iraqi people.”[6]

Indeed, during the war, American news organizations would continue to fetishize US technological superiority, while sanitizing “Iraqi casualties, Arab outrage about the war […] and the negative features of the war”[7] from American television screens. All of this discursive and visual manipulation of the carnage that truly existed on the real battlefield served to enable the process of selling the war to the US and the world.

————-

The US media’s complicity in selling the Iraq War to the American people is an important object of analysis when assessing how enormously consequential foreign policy decisions can be distorted and manipulated within democratic societies. It is a reminder that democratically elected governments can and do act in ways that appeal to our base emotions and greatest fears in order to push otherwise unpopular wars and initiatives. The mistakes of the Iraq War have been made, and the war’s consequences remain tangible to this day. Its perpetrators remain unpunished, and its greatest advocates have been rehabilitated in the era of Donald Trump.

But citizens should not forget the injustices of the Iraq War, nor should they forget how they remain liable to manipulation by governments, militaries, and indeed news organizations. We must remain mindful of the images that are sold to us, the language that is propagated to us, and the points of view that may remain hidden amidst the media spectacle. We must dig deeper into the stories that arise on our television screen and news feed. Fake news, it turns out, comes not only from Russian trolls – it may also come from the offices of The New York Times.

Featured Image: George Bush addresses the media 29/11/07. Photo by Chad J. McNeeley. Flickr Creative Commons.

Luca Brown is a U1 political science student at McGill University

_____________________________________________________________

[1] Heinz Brandenburg, “Journalists Embedded in Culture: War Stories as Political Strategy,” in Bring ‘Em On, ed. Lee Artz and Yahya R. Kamalipour (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005). 226.

[2] Ibid., 232.

[3] Ibid., 234.

[4] Ibid., 232.

[5] Mike Gasher, “Might Makes Right: News Reportage as Discursive Weapon in the War in Iraq,” in Bring ‘Em On, ed. Lee Artz and Yahya R. Kamalipour (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005). 213.

[6] Ibid., 213.

[7] Douglas Kellner, “Spectacle and Media Propaganda in the War on Iraq” in War, Media and Propaganda: A Global Perspective, ed. Yahya R. Kamalipour and Nancy Snow (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 74.