She Must Be a Witch: Beyoncé, Murder, and Society’s Fear of Female Power

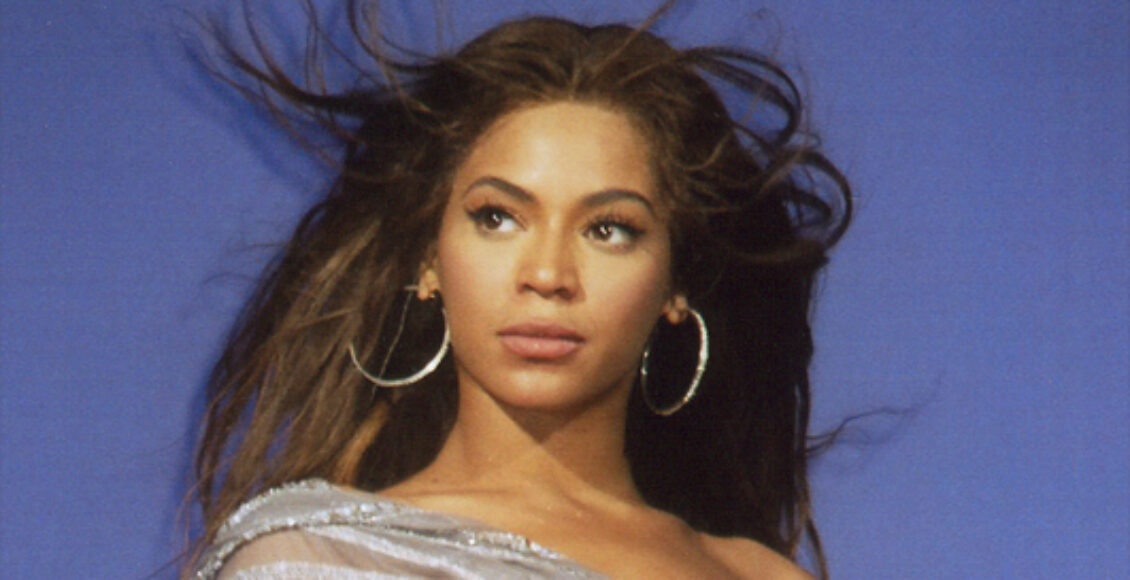

“Beyonce” By Jen Keys, is licensed under public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“Beyonce” By Jen Keys, is licensed under public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In an age where clickbait headlines and social media conspiracies thrive, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter has found herself unfairly entangled in the recent scandals surrounding Sean “P. Diddy” Combs — her name dragged into narratives fueled by misogyny and the relentless vilification of powerful women. Following Diddy’s arrest in September 2024 on federal charges of sex trafficking and racketeering, his signature white parties — once one of the most coveted events in the music industry — are now the subject of extensive scrutiny. These parties, allegedly venues for assault and exploitation, boasted guest lists filled with big names such as Usher, Justin Bieber, Donald Trump, The Kardashians, Jay-Z, and yes, Beyoncé. Despite the abundance of A-listers in attendance, it is Mrs. Knowles who has become the primary target of outlandish, maligning conspiracy theories.

Since the Diddy scandal’s eruption and subsequent discussions surrounding Beyoncé’s involvement, outlandish claims have emerged. The leading conspiracy theory claims that fellow artists who received an award for which the industry mogul was also in the running, must profusely thank and laud her to avoid “Queen B’s wrath.” These discussions point to instances such as Britney Spears’ acceptance speech for an MTV music award and Adele’s VMA acceptance, during which the British singer broke her trophy, dedicating the other half to Knowles.

The concept of ‘Queen B’s wrath’ refers to rumors that Beyoncé, conspiring with friend and close confidant Sean “Diddy” Combs, secretly orchestrated the deaths of her industry competitors, namely singers Aaliyah and Left Eye. Aaliyah rose to fame around the same time as Beyoncé and died in a plane crash in 2001. Left Eye, a member of the music group TLC, was killed in a car crash in 2002. These theories’ proponents suggest that Beyoncé feared Aaliyah and Left Eye’s potential to overshadow her popularity, “so [she] and others involved had [them] killed,” as written by one TikTok user. These theories have spiraled to the point of reinterpreting Kanye West’s infamous interruption of Taylor Swift at the VMAs in defense of Beyoncé as last-minute attempt to save Swift from becoming Beyoncé’s next target for failing to acknowledge her. Once shamed for his theatrics, West is now applauded for saving Taylor Swift, and the blame for this notorious moment in popular culture is now pinned on Beyoncé ––– a condemned man praised, a woman baselessly disparaged.

The vilification of women has been woven into the very fabric of human history. The case of Jeannette Rankin, the first woman elected to Congress, exemplifies this norm. When she voted against entering World War I in 1917, headlines focused solely on her, despite being one of 50 representatives to vote against the resolution. They painted her as hysterical, reporting that she appeared “that of a woman on the verge of a breakdown” and that “she pressed her hands to her eyes, threw her head back and sobbed.” Her male colleagues who voted the same way were portrayed as principal objectors, while she was reduced to an emotional, unstable woman, a characterization that would haunt her political career. This gendered portrayal of dissent demonstrates how even a woman’s reasoned political stance can be twisted into evidence of her emotional unfitness for power.

A century later, the press has deployed similar tactics against Meghan Markle, increasingly so after she and Prince Harry withdrew from their Royal positions. After Queen Elizabeth’s death, amidst mass mourning, Markle’s every move at the funeral was dissected and critiqued. As one article describes, “with an unreadable, almost blank face at the procession, Meghan was accused of disrespectfully smirking.” She was criticized for holding her husband’s hands as they entered Westminster Hall. The hate spewed at Meghan Markle has even been justified by calling her a “manipulative bully,” and therefore, deserving of the maliciousness. Royal biographer Tina Brown claims that Prince Harry was “like a lamb to the slaughter” in his relationship with Markle and that he “blindly followed her like a child.” Tabloids have released headlines claiming that the duchess’ attendance at a charity gala was “for the photographs.” Markle is portrayed as a ruthless social climber who broke up the royal family and faked pregnancies.

If Markle is painted as the woman who ‘destroyed’ the modern royal family, her narrative finds a striking predecessor in Yoko Ono. For over fifty years, Ono has carried the unfair burden of ‘destroying’ Britain’s most famous band, The Beatles –– so much so that ‘to be Yoko Ono’d’ has become a cultural shorthand for breaking up a group. Yoko Ono is a Japanese artist who gained international fame as a performance artist, and also as the wife of the band’s lead singer, John Lennon. In 1970 when The Beatles separated, the blame was pinned on Ono. As Ono and Lennon had married only a year prior, the media continuously claimed that Ono was responsible for the band’s disbanding. As a New York Times article puts it, “she was cast as the groupie from hell, a sexually domineering ‘dragon lady’ and a witch who hypnotized Lennon into spurning the lads for some woman.” Despite Yoko Ono being an accomplished artist prior to Lennon, a 1970 Esquire article mocked her accent, calling her “John Rennon’s Excrusive Gloupie.” The article criticizes Ono for a decision resting in the hands of the band members and ultimately beyond her control. The article, whose claims cannot be isolated from their sexist and racist undertones, features a photo of Ono’s “crime”— reading in the recording studio while her husband worked.

The ease with which many embrace these conspiracy theories reveals deeply rooted patterns of misogyny targeting powerful women –– an impulse seen throughout history, from Joan of Arc to the Salem witch trials. Social scientists argue that this perpetual vilification serves a specific purpose: to maintain traditional power structures by making examples of women who dare to accumulate too much influence. This pattern of demonization is not just based on individual bias –– it is a systemic pattern entrenched in cultural institutions, making it resistant to change. If any narrative deserves to be labeled as an absurd conspiracy, it is this profoundly embedded and practiced tradition of demonizing women –– but maybe that’s just wishful thinking.

Perhaps there was hope that we, as a society, had moved past these archaic ways. Looking across these womens’ experiences reveals a disturbing but clear pattern over time: when women gain significant cultural influence or challenge established power structures, they face eerily similar smear campaigns, regardless of the era. While the specific attacks are often calibrated to each woman’s perceived vulnerabilities, the underlying playbook remains consistent: they are painted as manipulative, inauthentic, and threatening to existing norms. These moments of cultural upheaval — whether it is a band breaking up, changes in the royal family, or an industry mogul facing accusations — become convenient catalysts for society to reveal its deeply rooted misogyny. The evolution from Ono’s treatment to attacks on Markle shows that while the language may have become more coded and the platforms for harassment more sophisticated, the fundamental impulse to delegitimize powerful women persists. Regardless of whether or not Beyoncé was actually involved in the crimes of Mr. Combs, no other person on ‘the list’ has faced the same degree of scrutiny. The virulent claims seek to paint Beyoncé as a criminal who, rather than earnestly working for her fame, extorted her way to the top. Female vilification campaigns seek to delegitimize and oust powerful women because it is apparently incomprehensible that a woman may amount to such success without stepping on (and murdering) others to get it. As Khaled Hosseini writes, “like a compass needle points north, a man’s accusing finger always finds a woman. Always.”

Featured image: “Beyonce” By Jen Keys, is licensed under public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Edited by Inès Salvador-Coumont.