Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot? Anglo-Scottish Relations Must Be Renewed in a Post-Brexit Britain

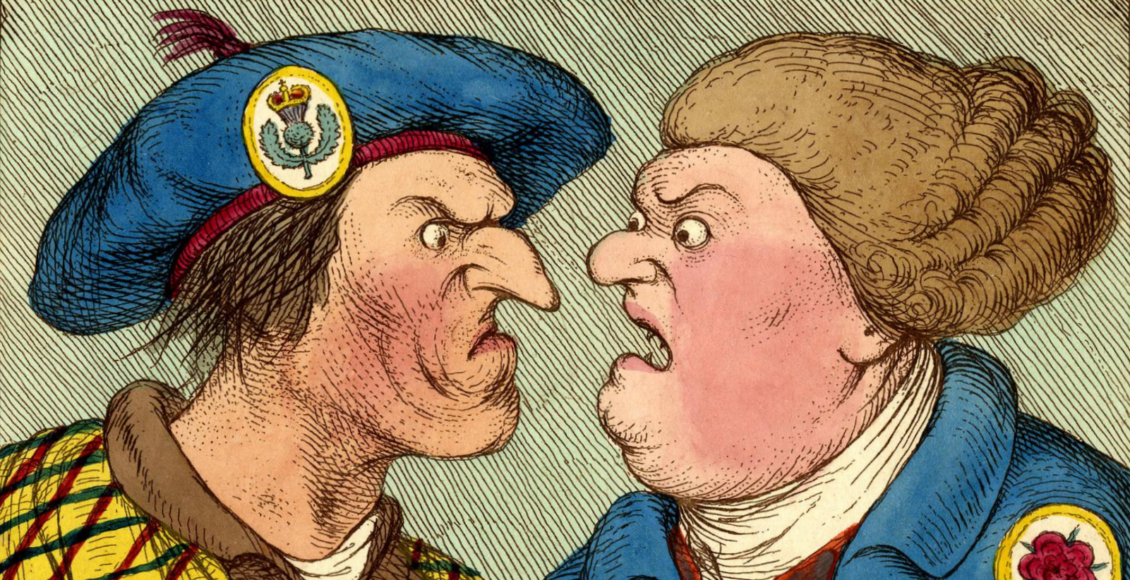

"Sawney Scot and John Bull", an eighteenth century print depicting historical animosity between the Scots and English. From the Trustees of the British Museum. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

"Sawney Scot and John Bull", an eighteenth century print depicting historical animosity between the Scots and English. From the Trustees of the British Museum. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

With the future of the United Kingdom potentially hinging on subsequent decisions by the UK government at Westminster, Anglo-Scottish relations have reached a pivotal crossroads in their long and complicated history. Following the Brexit referendum in 2016, Scots promulgated their desire to retain membership in the European Union, voting to Remain 62 per cent over 38 per cent, with the unique distinction of having a remain majority in all of its electoral districts. This heightened tensions between Holyrood — the Scottish Parliament — and Westminster, which further irked Scottish ire towards England in the hearts of those calling for independence.

Following the exodus of British MEPs from the European Parliament earlier this year, Scotland’s first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, accused Boris Johnson of having “denied democracy” in defence of her calls for a second independence referendum. Keeping with constitutional convention, the Prime Minister publicly dismissed this by refusing to grant any temporary powers that would allow for such a referendum. These political tensions have since bled into their differing responses to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, with Sturgeon criticizing Johnson’s back to work message as “premature” and urging Scottish businesses to ignore Westminster’s guidelines.

Though political tensions between Scotland and England have existed within the United Kingdom for decades, they must not be allowed to boil over lest the results be disastrous for all parties involved. Of course, this status quo is not merely a byproduct of Brexit; these tensions reflect long rising nationalisms throughout Britain, which originated in the latter half of the twentieth century. Since 1979, the willingness of those residing in England, Wales, and Scotland to identify as “British” fell considerably. According to the latest census data, this trend is particularly prevalent in Scotland, where only 8 per cent of Scots describe themselves as primarily British.

Commensurate with this above figure is the fact that Scottish nationalist zeal has manifested politically following the creation of Scotland’s devolved legislature in 1999. Ever since, the Scottish parliament has afforded a significant amount of agency to nationalist Scots by acting as a pulpit from which they can voice their grievances and rally support, as seen through the rise of the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP). Having held government in Scotland since 2007, the SNP and their cause gained considerable traction in the 2019 general election, when it clinched 13 seats in the House of Commons to control 48 of Scotland’s 59 electoral districts. This showing was considerably strong for the party compared to its losses at the hands of the Tories in 2017, indicating a Brexit-fuelled spike in Scottish nationalism. Indeed, recent polling suggests that a majority of Scots now favour independence from the UK, with one in five Remain-voting Scots — who decided against independence in the 2014 referendum — switching their vote to Yes.

https://twitter.com/NicolaSturgeon/status/1223380744833261570

Scotland’s first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, echoes desires to remain within the European Union. Via Twitter.

What transpired in Scotland reflects a much larger issue in the UK: the decline of Britishness, which has steadily occurred since the end of the Second World War. Before this, most Scots were stalwart supporters of their union with England from the late-eighteenth century onward, sharing in an overarching national pride in calling themselves “British.” As historian Linda Colley points out in her book, Britons, Scots increasingly began to see themselves as participants in a larger project of British imperialism, complimented by similar Protestant faiths and a shared industriousness, which superseded traditional Anglo-Scottish ethnocultural divides. These dynamics bound England and Scotland under a unifying sense of Britishness until the death knell of the British Empire was sounded in the mid-twentieth century.

Without a unifying identity to coalesce around, heightened nationalism in Scotland will continue to rise. So long as it does, the long term stability and survival of the United Kingdom cannot be assured. Scotland is a distinct nation, and its concerns should be taken seriously in a post-Brexit Britain. Paradoxically, arguments made in the stump speeches of pro-Brexit politicians, like Nigel Farage, played into this by espousing the language of independence. Though much as these self-proclaimed British nationalists argue that Britain has a right to self-determination without the interference from the EU, the SNP holds that Scotland, as a distinct nation, has the right to govern itself without the overwhelming influence of England. From the Troubles in Northern Ireland to the October Crisis here in Québec, the danger of allowing this status quo to persist unabated should appear self-evident when considering past experiences of nationalism within a multinational polity.

The ill-fated and illegal Catalan independence referendum in 2017 is only the latest example of this, and should serve as a warning to Boris Johnson and his successors on the untenability of current Anglo-Scottish relations. Indeed, SNP cabinet secretary Fiona Hyslop spoke of the referendum, stating “the decision over Catalonia’s future direction is a matter for the people who live there” and that “all peoples have the right to self-determination and to choose the form of government best suited to their needs.” While some might argue that Scotland’s devolved powers preclude it from seeking any such referendum, it is worth noting that a 2017 study found Catalonia to be one of the most devolved sub-national regions in the world. From this, we can gather that Scots are unlikely to drop their ambitions for independence miraculously, nor are they likely to accept the situation as it stands. Though Sturgeon has explicitly denied seeking an illegal referendum, with support for Scottish independence at an all-time high, the prospect of a Catalan-style vote in the future is certainly within the realm of possibility should tensions with Westminster continue to rise.

What, then, is the solution for restoring the amicable Anglo-Scottish relations that once existed in the UK? The answer is simple: Westminster must rekindle the sense of Britishness lost upon the demise of the British Empire. The hard part, however, is how this might be achieved. One possibility is to foster a new overarching British identity predicated not on antiquated ideas of empire, but instead a shared historical memory between two peoples who achieved more as Britons than they ever did as Scots or Englishmen.

According to a survey released in 2009, less than one-third of British pupils had taken a GCSE in history, a subject which is not mandatory after students reach the age of 14. This no doubt accounts for why the DailyMail reported that three out of four Britons had little or no knowledge of the Battle of Waterloo when asked on its bicentenary. What is required to reinvigorate British identity along these lines is the introduction of a more robust history curriculum, highlighting the achievements of the English and Scots alike by upholding the military heroism of Nelson and Abercromby, the technological marvels of Brunel and Watt, and the influential writings of Wollstonecraft and Hume as Britons. Of course, this paradigm would stretch beyond the restoration of Anglo-Scottish relations to exhibit Britain’s multicultural history as well, thereby incorporating its increasingly multicultural population.

Whatever the solution may be to ease current Anglo-Scottish hostilities, if the United Kingdom is to prosper and indeed be preserved, decisive action must be taken to create a new form of British identity around which the Scots and English can coalesce. Just as Scottish nationalists may take inspiration from the experience of Catalonia, Westminster should heed its example of the ills that can come from allowing a lack of unifying identity to persist. Should Holyrood decide to seek an illegal independence referendum, and if any violence is indeed committed in the name of such a goal, the whole of Britain would only stand to lose.

Featured image: An eighteenth century print depicting historical animosity between the Scots and English. “Sawney Scot and John Bull” from the Trustees of The British Museum is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. No changes made.

Edited by Asher Laws