South China Sea: The Stand-Off Explained

Rodrigo Duterte, the current President of the Philippines, recently stated the country will no longer challenge China’s claims in the South China Sea. This comes only weeks after China has warned Singapore to stay out of the disputes illustrates that the hostilities over the South China Sea are as volatile as ever. To understand the significance of these developments it is crucial to understand their context and the history of the territory itself.

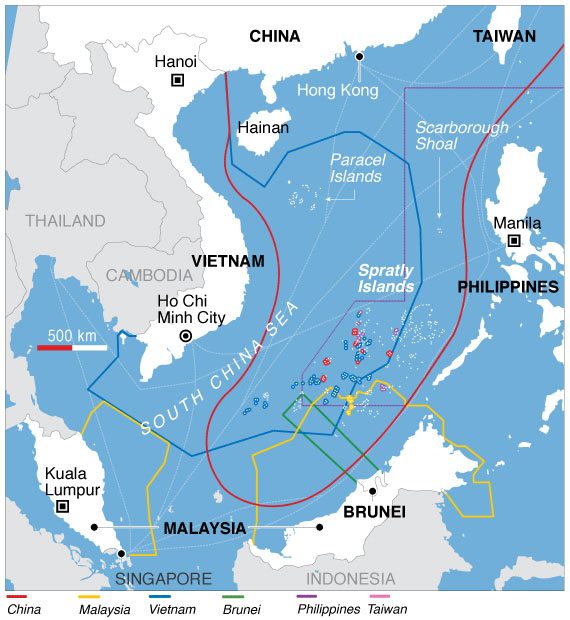

The South China Sea lies just below China and finds itself surrounded by several Southeast Asian nations. Many of these nations, including China, Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan, have competing claims over their exact territorial boundaries within the sea. The area is significantly valuable for its ecological, environmental, and strategic merits. It holds deep oil deposits, natural gas, large fish populations, and acts as a vital trading lane that connects the Pacific to the local nations. Each country is eager to establish a credible territorial boundary that can allow them to exploit these benefits.

These sovereignty claims have covered the entire scope of the area but are especially disputed over two central chains of islands — the Paracels and the Spratlys. China claims the islands fall within their “nine-dash line” which is the large portion of the sea they insist has been under Chinese rule since the early twentieth-century. Each nation, especially Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines, likewise claim several of the islands either have been under their sovereignty or should be, under international law. These nations base their claims on the stipulations found in the United Nation’s Convention on the Law of the Sea, but China has largely ignored international legal norms, which they insist are tools for restricting their growth.

These disputes, which recently haven’t induced much more than heightened diplomatic threats and warnings, had led to confrontation in the past. China and Vietnam clashed over the islands in 1974 and 1988, with only Vietnam suffering casualties in both cases. Since these incidents, the closest thing to a significant conflict has been the military standoff between China and the Philippines in 2012, and Vietnamese accusations that China sabotaged a Vietnamese oil company’s operations in the same year.

China has so far been reluctant to compromise on their stance. They have favoured bilateral negotiations with regional countries, but the smaller nations fear China will use its diplomatic and economic strongholds to reinforce its claims. With many of the claimant countries being a part of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), there have been calls for China to negotiate through the regional organization, but this has also found little success.

The contentions are not only voiced by the bordering regions. Various international groups and states have intervened or taken sides in the matter, with the most involved being the United States. Americans have used their international ties with the Philippines as a pretext for inserting themselves into the situation. They have commonly deployed vessels and conducted naval test operations in areas they argue are open sea lanes. The United States claim these actions are not meant to check China’s growth but merely to defend international law.

In the meanwhile, the Philippines seeking international arbitration via the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague rendered significant development in the course of the conflict. On July 12 the court ruled in favour of the Philippine’s claims that China was unwarranted in their pursuit of dominance in the region and that their nine-dash line had no legal justification. Despite China’s refusal to recognize the ruling of the court, the decision ostensibly gave a significant boost to the Southeast Asian nation’s bid for representation in the region. This was of course until Duterte’s recent flip, which essentially nullified the progress for the smaller nations whilst reaffirming China’s authority over the Sea.

The Philippines’ shift away from the United States in favour of China not only creates tension within ASEAN but also brings the American role in the area under contestation. In reality, the resources therein and the Sea’s provision of an efficient trade route are vital for the United States. No longer being able to justify their actions through international good-will and obligations to the Philippines could force the Americans to adjust their stance and presence within the area — a change they will not take kindly to.

Within ASEAN, the Philippine’s reversal has caused internal dissent. The question of how to address the dispute with China has become more convoluted than ever. The association prides itself on unanimity but the internal split over the South China Sea crisis puts a strain on its unity. Yet none of the state actors who are involved in the crisis are likely to rescind their territorial claims. ASEAN will continue to try and negotiate; Beijing will continue trying to strong-arm their neighbours; and Washington will continue fighting for a safe and communal territory that can guarantee open trade routes. Since none of these nations are looking to back down, animosities over the South China Sea certainly will not dissipate in the immediate future.