The Brain Drain, the Civil War, and Angola’s Public Health Crisis

The Angolan Civil War began as a proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union. After successfully ending Portuguese colonization, the three liberation parties within Angola now had the task of deciding who would form the new government. While the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) was defeated relatively quickly, tensions remained high between the Soviet-backed Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and US-backed National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). Both parties received an influx of weapons, money, and training from their respective patrons, reflecting the conflict between the two superpowers while avoiding the inevitable mutually assured destruction that would occur in the case of a direct US-Soviet war.

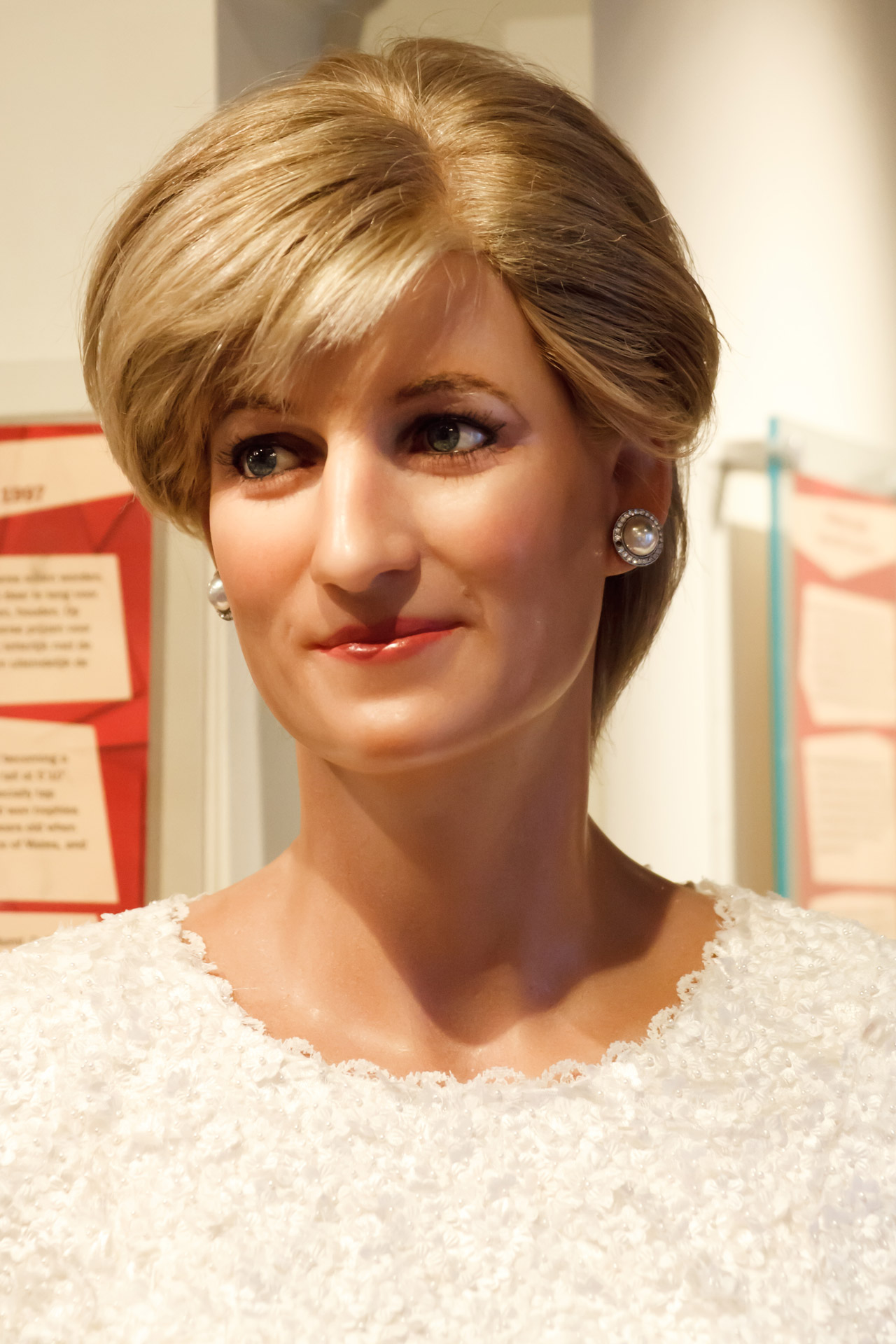

Even as tensions between the two countries thawed, the war between UNITA and the MPLA continued. Both factions continued to fund themselves through Angola’s wealth of resources. Joseph Savimbi’s UNITA controlled the diamond-rich interior while Jose dos Santos’ MPLA held Luanda and the oil-rich coastal area. Multiple efforts were made in the 1990s to promote peace and unity but Savimbi, not wanting to lose his power and resources, continually shut down peace talks. It was not until Savimbi was assassinated in 2002 that lasting peace became a legitimate possibility for Angolans.

The 27-year civil war had a devastating effect on Angola’s economy and infrastructure. Many of the Portuguese-established colonial institutions like schools, hospitals, and bridges, had been destroyed or dismantled during the war. Instead of using the country’s mineral wealth to maintain these institutions, Jose dos Santos used the money for personal patronage and to fund the war.

The war, compounded by the instability, led to a brain drain in Angola as many of the country’s educated elite fled to South Africa and other nations. This led to a vacuum in Angola’s skilled labour force that has continued even a decade and a half after the war, this is compounded by the fact that nearly half of the Angolan population is under the age of 15. One of the sectors that suffered most during and after the war was the public health sector. Approximately 70% of Angolan doctors practice abroad and while stable African countries like Botswana manage to retain most of their doctors, approximately 40% of physicians from countries that had experienced a civil war in the 1990s had emigrated (this included nations such as Sierra Leone, Angola, and Liberia). In 2009, Angola had only 1 physician per 10,000 inhabitants while Canada had 20 times that amount for the same year.

Even after the war ended, the dos Santos government did not invest much into healthcare. Although free public healthcare is a right defined by the constitution, the lack of doctors and rural access to hospitals means that most middle-class Angolans rely on private clinics. For those who live outside Luanda’s (Angolan capital) metropolitan area, access to reliable healthcare is even more scarce. In 2017, the Angolan federal government spent 4.3% of its federal budget on healthcare, compared to the Canadian federal government’s 11.5%. These factors–a lack of hospitals, the physician brain drain, the labour vacuum, and the lack of government spending on public health–have led to the maelstrom that is Angola’s current public health crisis.

Even a decade and a half after Angola’s Civil War, the effects of its brutality continue to be felt. Over 88,000 Angolans have been disfigured by landmines and countless more have been killed. Estimates state that over 10,000,000 landlines still exist in rural areas of the country, looming over citizens as a remnant of the country’s dark past. Furthermore, the large minefields that still exist in parts of rural Angola prevent development and leave large swaths of the country too dangerous to visit. Access to physical rehabilitation clinics remains difficult for residents of rural Angola, and for those within Luanda or other urban centers, many rehabilitation clinics remain crowded and understaffed. NGOs and charitable organizations have stepped in to fill the gap, outfitting tens of thousands of amputees with prosthetics and wheelchairs, as well as promoting community and sports-based physical therapy to ensure that disabled Angolans maintain full inclusion in Angolan society. Mine-removal is both a costly and time-consuming task. In 2015 alone, there were 15 reported deaths due to landmines and 29 reported injuries although officials estimate that the actual number is higher. Furthermore, the number of mines in rural areas means that rural Angolans, who are often poorer than their urban counterparts, cannot expand their farms or villages due to fears of unmarked or unexploded mines.

Another major issue in Angolan public health is the country’s high maternal and infant mortality rate. Angola has only 1 hospital bed per 10,000 patients and 0.1 midwives per 10,000 patients, meaning the vast majority of Angolan woman do not get pre-, peri-, or post-natal care, especially those in rural areas. Just under 20% of Angolan children do not make it to age 5, often dying of treatable or easily preventable infections, and the maternal mortality rate for live births is 68 times the Canadian maternal mortality rate. A huge part of this issue is lack of access to safe, clean water. The water sanitation system is another structure that was largely destroyed during the civil war. Only half the population has access to clean drinking water but the urban-rural disparity is nearly 50%, with 75% of urban Angolans having access to safe water while only 28% of rural Angolans do. In addition, only 22% of Angolans had reliable access to sanitation while 89% of urban Angolans did. The leading cause of death in children is diarrhea, which is entirely preventable given that children have access to safe water. While the government has made outreach efforts to solve the water problems plaguing rural Angola, the issue is systemic. Much of the infrastructure in rural Angola was destroyed or fell into disrepair during the war and is currently outdated. However, budget constraints and mines mean that the education and rebuilding process is slow.

Diseases like cholera, malaria, and yellow fever thrive due to Angola’s tropical climate and the lack of sanitation in rural areas. Many Angolans have died from the effects of drinking polluted water, a fact that UNICEF states could be rectified through education and water treatment programs. Although nearly half the country’s population is under 22, only 3.5% of the country’s GDP is spent on education; classrooms and schools are overcrowded and underfunded while teachers are overworked and underpaid. This perpetuates the brain drain as many young Angolans leave to find better educational opportunities in Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) countries, South Africa, or the US. In addition, this means that many young mothers and families may not be educated about the importance of clean drinking water. With only 1.66 nurses per 10,000 people (mostly based in Luanda and other urban areas), Angola also utilizes NGOs and the WHO for vaccinations and disease education, especially in the wake of the 2014 oil crash that devastated the Angolan economy. Although widespread vaccination has reduced child and infant mortality rates in the country, outbreaks of yellow fever and measles have plagued the country in recent years.

An indirect impact of Angola’s public health problem is the pharmaceutical drug shortage in 2018. Since oil accounts for 95% of Angola’s exports, the country’s economy is almost entirely based on world oil prices. The country has still not recovered from the 2014 recession and this can be seen in the public health sector, especially in rural areas of the country where individual doctors can see hundreds of patients a day and where vital medications needed to treat tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and other diseases are in very low supply. Wait times for drugs even in Luanda hospitals are dangerously long due to red tape and bureaucracy. Meanwhile, the economy’s poor state means that wages for public health officials such as nurses and doctors are very low, further encouraging many of them to emigrate for better opportunities or move into private clinic work.

The Angolan government, as well as foreign governments and NGOs, are being proactive in fixing Angola’s brain drain and healthcare problem. Cuba, which has one of the highest amounts of physicians per capita in the world, has sent thousands of doctors to Angola to both teach and practice within the country. Other Lusophone countries, such as Brazil and Portugal, have also sent doctors to the country. However, these are stopgap methods for the real issue; since foreign doctor exchanges are mostly paid for with oil money, the same amount of money could be invested in homegrown doctors to ensure consistency and reliability in case the oil economy dips in the future. Non-governmental organizations, such as Red Cross and OK Prosthetics, fill the void left by the lack of medical staff and facilities in the country and allow ill or disabled Angolans to fully participate in society; they often also provide vaccines and primary healthcare to infants and peri- and post-natal mothers.

Both the dos Santos and Lourenco governments had promised to increase the number of trained physicians as well as the amount spent on healthcare within the country; mortality rates have been steadily decreasing since the end of the war while life expectancy has increased. The Angolan Ministry of Health especially hopes to tackle the disparity in healthcare access between urban and rural Angolans by increasing the number of medical school graduates in the country, cracking down on counterfeit narcotics, and proactively destroying and dismantling mines. New President João Lourenço ran for the MPLA based on a platform of anti-corruption and accountability, promising lasting and effective change for Angolans. So far, his technocratic government has been lauded for removing some of the ‘old guard’ dos Santos loyalists who had benefited under the former president’s patronage-based presidency. The effects of this have already been seen – Angola’s National Demining Institute destroyed over 14,500 mines in May alone of this year, reflecting the new government’s serious approach to public health and safety within the country.

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo