The Challenge of Enforcement: New Laws in New Lands

If you’ve read my last posts on the TPP, you will have noted that one of the things that I’ve outlined that the deal promises is that all countries “adopt and maintain in their laws and practices the fundamental labour rights as recognized in the ILO 1998 Declaration.” This would broadly include things like: an end to forced labour and child labour, allowing workers the freedom of association and collective bargaining, etc. In most of the countries involved in the deal these sorts of laws are already in existing legislation. The question as I’ve pointed out in my earlier post is not if any labour code exists but whether or not it can be enforced.

In Vietnam, for example, there are some laws that exist whic h prohibit the work of children under the age of 15 if the Ministry of Labour deems it to be unfit. Yes, this does not completely rule out child labour but in cases where labour for children under the age of 15 is allowed, the Vietnamese Labour Code still provides them some sort of protection: “Employers may only employ young workers in work suitable to their health so as to ensure their physical, mental and personal development…The employment of young workers shall be prohibited for hard, dangerous work and work exposed to harmful substances…” Even though this legislation exists, slave labour for children still exists there, making these proposals for labour laws a hollow move. This post is not specifically about the TPP however, (I think I’ve spoken out about it enough) but about the main challenge facing developing countries in terms of workers’ rights: the enforceability of new labour laws and international standards.

h prohibit the work of children under the age of 15 if the Ministry of Labour deems it to be unfit. Yes, this does not completely rule out child labour but in cases where labour for children under the age of 15 is allowed, the Vietnamese Labour Code still provides them some sort of protection: “Employers may only employ young workers in work suitable to their health so as to ensure their physical, mental and personal development…The employment of young workers shall be prohibited for hard, dangerous work and work exposed to harmful substances…” Even though this legislation exists, slave labour for children still exists there, making these proposals for labour laws a hollow move. This post is not specifically about the TPP however, (I think I’ve spoken out about it enough) but about the main challenge facing developing countries in terms of workers’ rights: the enforceability of new labour laws and international standards.

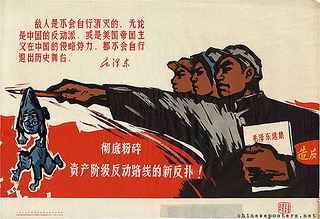

I will speak about a case which I know to a certain extent somewhat well and that is the case of China. China, as a communist state (now mostly only in name) has always placed a large emphasis on the worker, evident in its founding document which largely follows Marxist rhetoric. In a post-Maoist, globalized and mostly capitalist world though they have come to value the almighty profit margin. This is not to say that China has not made great advances in labour legislation, clearing, abolishing or modifying almost 200 000 new laws. But again, the problem is enforcement, Mary Gallagher, a professor at the University of Michigan sums up the problem in China quite well: “high standards, low enforcement.” Reasons for this situation are similar as in other countries. One reasons is the short and narrow time frame in which these laws came to be. In China, much of the new labour standards came in the last 20-25 years where the US had almost 200 years to sophisticate their labour legislation. Another reason and the more prominent one, is the government’s obsessions with political stability. Because of this most governments in developing countries will throw money at worker’s grievances and expect them to go away and expect people to turn a blind eye. In some instances people will not accept mediation but in most cases, government money has made the “problem” go away, so to say. If you’d like to know about this case in greater detail, I recommend you read an article I wrote in the spring about the subject.

This all being said, the solution to enforcement will not come from standards set by the ILO or international trade deals or from government legislation, it will come from the grassroots part of the labour movement. That is how labour rights have always been won. In the next post, we will look at these grassroots labour movements in developing countries and see how they are faring in their quest for a fairer workplace.