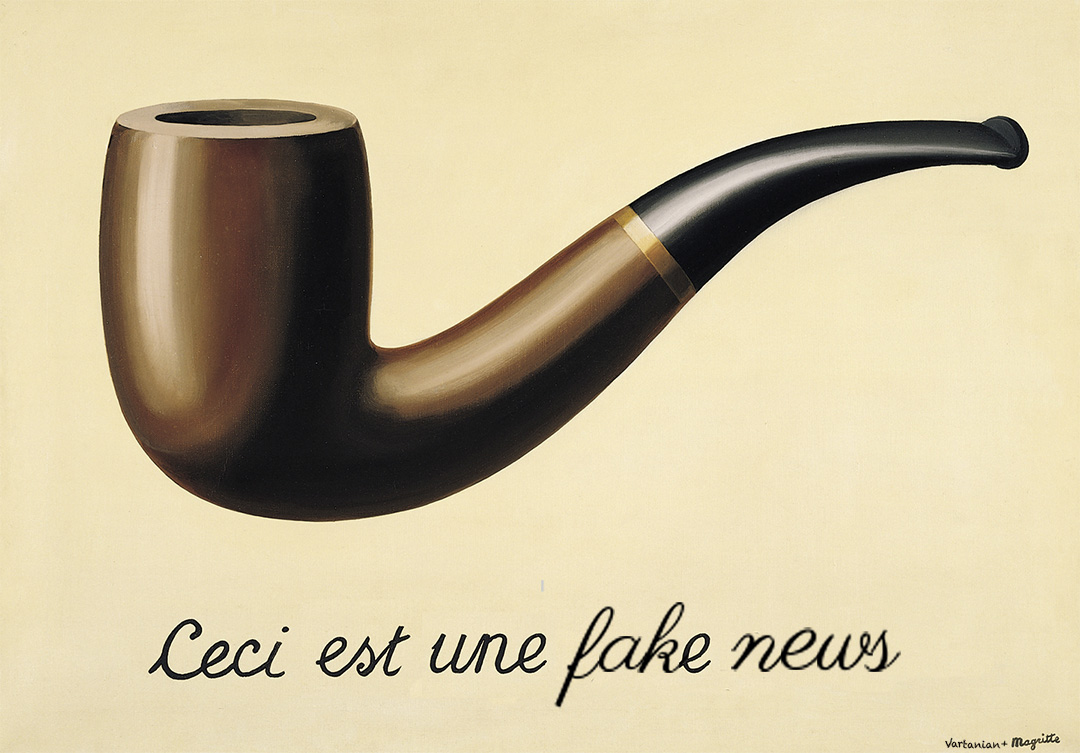

The End of Fake News?

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/hragvartanian/32940251834/

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/hragvartanian/32940251834/

In January 2018, French president Emmanuel Macron resolved to make fake news a thing of the past with an unprecedented anti-fake news law project. Speaking at the annual presidential New Year’s speech, he explained that its aim will be to dampen the effects of fake news on public opinion. This announcement comes just months after Macron’s successful presidential campaign, during which he was regularly the target of online defamation. While the French president hopes that fake news legislation might break electoral misinformation patterns, opposing voices have risen to highlight its potentially counterproductive effects.

Since the 2016 American election, fake news have become a major culprit for the weaknesses of the modern democratic system, particularly electoral volatility. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter have made it increasingly possible for users to share information that is unfiltered, but also unverified, causing around 75% of American Internet users to believe fake news, as shown by a recent study. Considering that there were over 750 million recorded clicks on fake news articles during the presidential campaign, their ability to steer public opinion and voting behaviors has become widely acknowledged. The large-scale media credibility crisis born from this reality has left leaders of all fronts, as well as international political figures, fearful for their reputation and jobs.

In France, news articles alleging that Emmanuel Macron was in a secret relationship with Mathieu Gallet, Radio France’s CEO, emerged during the 2017 presidential campaign, rocking the electorate’s trust in the then-candidate. Another rumor, which spread on the eve of the first round of voting via Twitter, alleged that Macron was committing tax fraud through offshore accounts. Since an obligatory 48-hour media blackout, called “reserve period“, was being enforced at that time as is traditionally the case with every election, Macron’s team was unable to respond. This created tension and uncertainty among an already divided French population, just hours before voting was set to begin. Although these fake news didn’t cost Macron the presidency, they have left a vivid imprint on national politics and the media landscape.

With this in mind, the anti-fake news law championed by the French president aims to strengthen the stability of liberal democracy, particularly during periods of electoral campaigning. A first measure is meant to tackle the issue of online transparency. Designed to mandate websites to disclose whether their news content is sponsored and by whom, this provision would allow users to recognize false information and prevent it from being labeled and spread as legitimate news.

A second measure, which garnered substantial criticism, would go beyond simply categorizing online content and bar access to fake news items all together. A specially-designed legal procedure would allow any user to immediately appeal to a judge for the removal of false content, or to eventually block access to misleading websites entirely. Dissenters fear that this would curtail free speech and deteriorate the foundations upon which liberal democracy rests, rather than strengthen them as Macron hopes.

The question of what constitutes free speech in the Internet era, whether it should be supervised and by whom is thus at the core of the controversy. Emmanuel Macron’s camp feels that the Internet, as a publicly-accessible domain, should be subjected to the same rules as any other public platform. Currently, in France, the CSA (Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel) is the body in charge for regulating electronic media, and has been since the 1980s. The media watchdog, for instance, requires that presidential candidates speak for the same amount of time as one another when campaigning, both on the radio and television, in an effort to avoid media favoritism. Other than overseeing political campaigns in the media, the CSA seeks to protect minors, the “dignity of persons“, and the veracity of information. Macron and his following thus deem it logical that its duties be extended to new forms of Internet media.

Critics of the anti-fake news law, which include Front National leader Marine Le Pen, have expressed their concern for what they consider to be a “worrisome” piece of legislation, whose goal to “muzzle” citizens is, in their view, akin to censorship. They argue that delegating the task of distinguishing between “real” and “fake” news to a third party, such as the CSA or a judge, is anti-democratic. Instead, they request that freedom of expression on the Internet continue to be guaranteed, even if it manifests itself as fake news or offensive commentary.

Macron’s position also contrasts deeply with that of the United States government, where many contend that fake news media moguls, such as Steve Bannon, were instrumental in Donald Trump’s ascend to the presidency. As such, the probability that they should soon come under White House scrutiny is highly unlikely.

Beyond political adversity, crafting an anti-fake news law without a blueprint thus stands to be Macron’s biggest challenge. The line between guaranteeing quality information and suppressing free speech is thin, and will have to be determined with patience and caution.

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo