The EU Claims to Outsource Border Security to Tunisia — Is It Really Outsourcing Oppression?

A used clothing market operates just inside Bab El Kasbah at Sfax, Tunisia.

A used clothing market operates just inside Bab El Kasbah at Sfax, Tunisia.

In December 2024, an 11-year-old girl was rescued from the Mediterranean Sea — just off of the Italian island of Lampedusa — after floating for three days with only an innertube and life jacket. She was starving, exhausted, and suffering from hypothermia. Originally from Sierra Leone, she was one of 45 migrants on a boat destined for Italy. She is now one of at least 15,000 African migrants in transit in Tunisia, most of whom are determined to reach Europe.

Since 2014, the European Union (EU) has strengthened its internal border control by increasing the length of border walls and fences by 75 per cent. Border barriers now stretch 2,000 kilometers across Europe. The EU has also invested billions of dollars towards their Coast Guard agency and plans to fund equipment for night vision and drones. Consequently, migrants have resorted to more perilous means to reach Europe.

In concert with the above-mentioned border control policies within Europe, the EU has accelerated and fortified its externalisation policy, outsourcing security to non-EU states bordering Europe, such as Turkïye, Libya, and Tunisia. An early example of this policy was the 2016 EU-Turkïye deal. According to this deal, irregular migrants — people who migrate outside of legal or regulatory frameworks — seeking to enter Greece were diverted to Turkïye. In exchange, the EU provided Turkïye with financial aid and political concessions.

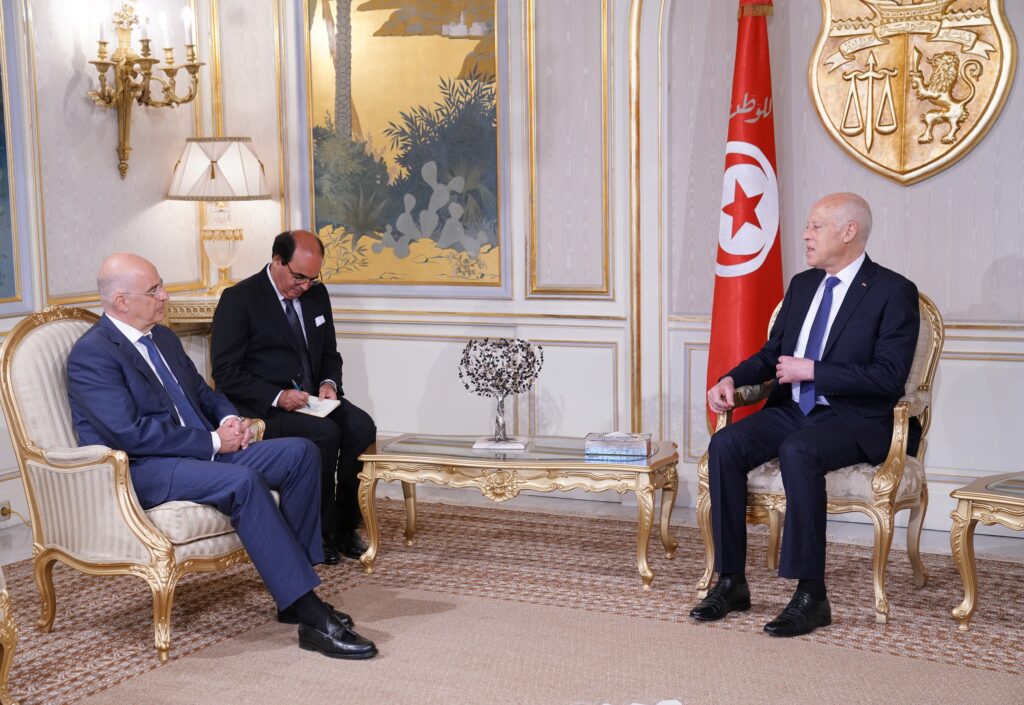

The EU’s externalisation policy has been replicated in Tunisia. It has been facilitated and exacerbated by Tunisia’s autocratic President, Kais Saied. This process has come at the expense of human rights and, paradoxically, has been ineffective in averting irregular migration to Europe.

Due to social, climate, and economic turmoil in sub-Saharan Africa, Tunisia — located between sub-Saharan Africa and Europe — has become a central migration hub for those seeking to reach Europe. However, it has proven to be an unwelcoming destination for these migrants due to anti-Black racism propagated by Saied and the ensuing abuses perpetrated by Tunisian security forces.

The COVID-19 outbreak exacerbated Tunisia’s already fragile economy. In response, President Saied embraced increasingly authoritarian policies. In 2021, he dissolved the government and suspended parliamentary activities. He has used sub-Saharan migrants as scapegoats by inciting anti-Black racism to distract from Tunisia’s worsening economic crisis and democratic backsliding. In a February 2023 speech, he claimed that “the undeclared goal of the successive waves of illegal immigration is to consider Tunisia a purely African country that has no affiliation to the Arab and Islamic nations,” which unleashed a surge of violence against Black migrants, as well as Black Tunisian citizens who make up ten per cent of Tunisia’s population.

Despite Saied’s xenophobic rhetoric, the EU — concerned about rising migrant inflows — seized on Tunisia’s growing social and economic instability to expand its externalisation policy. In July 2023, a new deal was ratified in which the EU agreed to grant millions of dollars to Tunisia in exchange for tighter migration controls. In July 2024, the Tunisian government approved a draft law for a €50 million loan from Italy, officially designated as aid to the energy sector. However, human rights groups warn that this may be a guise for funding border control efforts without accountability for human rights.

Indeed, migrants intercepted by EU-backed Tunisian border control forces have faced horrific violations. Thousands of migrants have been dumped in deserts along the Tunisian border with Algeria and Libya, where they are often robbed, beaten, and sexually assaulted by Tunisian security forces operating with impunity. Reflective of a broader trend of horrific abuse is the story of a 28-year-old Guinean man referred to as Moussa. Moussa attempted to cross to Italy from the eastern Tunisian town of Sfax but was intercepted by Tunisia’s National Maritime Guard in February 2024 and brought back to Tunisia near the Algerian border. There, he witnessed the systematic rape of women, including a pregnant woman beaten until she bled and fainted. It is believed that nine in ten female African migrants arrested near Sfax have endured sexual violence or torture.

Sfax — the town that Moussa initially departed from — has become a migration hub, and has therefore also developed a prosperous migration economy centred on boat-building, temporary accommodation, and smuggling services. Migrants who pay for smuggling services have experienced exploitation and torture. Some reports indicate that there is collusion between Tunisian security forces and human smugglers.

Migrants have started to make the journey independently, alarmed by Saied’s racist rhetoric and the rampant abuse it has perpetuated. Their lack of knowledge and relationships with local authorities, however, has led them to take more dangerous routes across the Mediterranean. Between January 2014 and June 2023, the Mediterranean crossing from Libya or Tunisia to Greece or Italy, accounted for over 22,000 of the 28,000 migrant deaths and disappearances recorded in the Mediterranean. The crossing has thus earned the title of the deadliest migratory route.

The EU continues to deal with Tunisia because the implemented securitisation measures, including the development of border management systems and migrant interception capabilities, are believed to be a successful policy. In actuality, the most significant outcome of securitisation policies is neither a reduction in migration nor the elimination of smuggling networks, but rather a rise in the cost of smuggler services and greater risks for those reliant on them. Contrary to the EU’s objectives, migrant arrivals in Italy have risen since 2020, mainly due to Saied’s xenophobic comments and Tunisians’ subsequent attacks on sub-Saharan migrants, which have pushed them out of the country. The increase in migration to Italy suggests that the EU’s attempts to curb migration through externalisation policies have not, and most likely will not, succeed.

In October 2024, Saied secured another presidential win with a meager voter turnout of 28.8 percent — raising Tunisia’s red flag in more ways than one. Since then, repressive state policies, particularly targeted towards activists trying to shine light on migrant abuses, have only worsened. This prompted an EU spokesperson to announce that over the next three months, subcommittees would be established to safeguard human rights in Tunisia until 2027, indicating that the EU is beginning to acknowledge their role in the conditions faced by migrants.

Notwithstanding this, the EU-Tunisia migration deal clearly reflects the humanitarian failures of the EU’s externalisation policies. Although the EU prides itself as a protector of human rights, the agreements with Tunisia, as well as many other countries, fund oppressive regimes that make migrants susceptible to violence. The EU claims to externalise security, yet it appears more disposed to externalise human rights violations.

Edited by Grace Hodges and Daniel Harris

Featured image: “Bab El Kasbah: A used clothing market operates just inside Bab El Kasbah at Sfax, Tunisia.” by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0.