The Hour of Informal Economy : Challenging Unemployment in Rwanda

source: "Scene of life" by @jorgegascon (instagram)

source: "Scene of life" by @jorgegascon (instagram)

In the wake of the genocide against the Tutsis, there was an understandable sense of general panic in Rwanda. Though the bulk of the atrocities were finally over, no one felt reassured; the calm after the storm resonated more as apprehension than quietude. I once asked my father: “why did you stay?” It was chaos and turmoil, so why not escape?

My father replied to me: “And to let this country disappear? Never.”

According to President Kagame, when it came to rebuilding the nation, “everything was a priority.” Mere improvement was not enough; Rwandans had to press the “restart button” and make sure that this time, things would be fundamentally different. But how? The President noted three things: “we chose to stay together, we chose to be accountable to ourselves, and we chose to think big.”

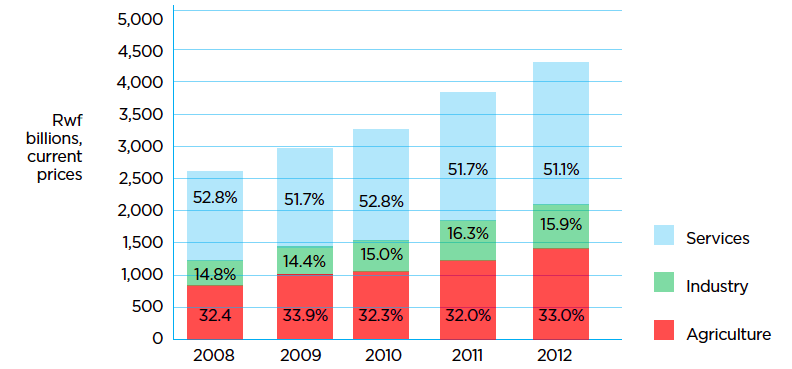

For the next 25 years, Rwanda dedicated its efforts towards recovering from war, to become a regional force in East Africa. The establishment of a stable government in which security was restored revived new sentiments of trust and confidence in political institutions. This was a crucial step for economic development. After 2006, the economy began to expand, gaining momentum. Driven largely by strong performance in service, agricultural and industrial sectors, Rwanda’s GDP growth rate rose to an annual average of 7.5% over the past decade. On a national level, such consistent expansion over a large period of time has made Rwanda one of the fastest-growing nations in Africa, only surpassed by Ethiopia.

source: EDPRS II, www.minecofin.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/documents/NDPR/EDPRS_2.pdf, 29.

About every year and a half, I return to Kigali. About every year and half, I notice new skyscrapers, hotels, restaurants, and roads built to replace the unpaved ones of the past. For many, Rwanda has become attractively unrecognisable as it constantly evolves before our eyes. This being said, focusing on the bigger picture can tend to hide the faults in the details. Despite surmounting complex obstacles in re-building state capacity, the challenge of creating sustainable and equitable growth remains. On an individual level, most Rwandans live below the absolute poverty line, estimated at $1.25 per day. In addition, inequality rates suggest a wide disparity in incomes and as of 2019, the rate of unemployment is estimated at 16%.

The agricultural sector employs over 60% of the total workforce. Most of the non-farming jobs are concentrated in the informal economy, an area where employment is unregistered and unreported, and thus is unprotected by the government. There, the workers do not pay taxes to the government and their work is not regulated by the law. Though the informal economy generates only about 17% of Rwanda’s total output, 90% of all firms, the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), are informal. Critics of informal markets argue that they should be criminalised because they do not contribute to the government’s tax revenues. However, this neglects the changes that adjusting economies undergo as they develop. In Rwanda, high economic growth has prompted a rise in urbanisation, as more people are moving from the countryside to the cities in search of work. But job vacancies are not opening fast enough to match the growing numbers of rural migrants. In this context, the informal economy acts as an economic reliever by filling the gap between the rural and the urban job market. With over a million household enterprises, the sector welcomes the most unconventional and unskilled jobs, creating opportunities for everyone.

Luckily the Rwandan informal sector is supported by the government, which plays in the best interests of agricultural workers. Since higher rates of poverty are found among farmers with low productivity and undiversified crops, the state support of the informal sector facilitates the workers’ transition from the agricultural sector to the industrial sector. Taking this approach, the government contributes to poverty reduction.

Understanding that the Rwandan economy is undergoing economic transformation helps to explain the fluctuating levels of employment; however, beyond the numbers, I wanted to hear the real-life stories of local entrepreneurs and understand what they needed to expand their business activities.

This led me to Joseph, a Rwandan entrepreneur with a small business selling kombucha that he mixed with caffeine and alcohol. Joseph had learned to make kombucha, a fermented tea drink, in Kenya and came back to Rwanda, hoping to develop an expansive firm with a unique product for Rwandans.

With only one associate and working from his home, Joseph was able to produce large quantities and sold over 200 boxes every day, all thanks to a single large client he had approached—a popular nightclub in Rwanda. As Joseph’s business was growing and becoming widely consumed, he needed official documentation for his business, but especially for his product, to obtain a quality control certificate (ubuziranenge). In the course of applying for formal business qualifications, scientists paid visits to Joseph’s kombucha factory and inspected the environment. They noted that his facility was too small and too poorly equipped for the large production. As a result, Joseph found himself backed against the wall: to expand his business and pass quality control he needed a better facility, but building a better facility required more money than the bank could lend him, considering his low earnings. Joseph could not comply with the regulations—and his business was seized.

Shortly before losing his company, Joseph had piqued the interest of a wealthy investor, curious about Joseph’s “secret formula.” The wealthy entrepreneur approached Joseph’s right-hand man with the intention to learn how to make kombucha. Joseph’s associate agreed to sell him the formula for 200 000 Rwandan francs (just under $300). Then, at the same time as Joseph’s business was being seized, the wealthy investor opened his own kombucha business. With a better facility, a viable work environment, and a product safe for consumption, the investor quickly obtained a certificate for quality control. Joseph’s hope of being the first to provide the unique drink in Rwanda vanished and his competitor took the upper hand.

To level the playing field and allow small enterprises to have the opportunity to expand their business capacities, the underlying issues must be resolved. Most of the reforms conducive to private sector growth benefit new investors and larger firms, which account for only 5% of total employment, while small entrepreneurs are often overlooked. For instance, access to finance is very difficult for most firms in Rwanda independent of their size. However, compared to wealthier entrepreneurs, who can expand despite the financial barriers, MSME employers are disproportionately affected because they have minimal starting capital. As Joseph explained, “business is a matter of confidence. If my clients think that I will grow, they will invest in me. If my workers think I will grow, they will be loyal to me. But before that, I need someone to believe in my project.” Without access to finance, many small entrepreneurs have no one to believe in their entrepreneurial capacities and help make them a reality.

Fortunately, a few economic actors understand the importance of investing in one another, and these actors are working to provide greater access to educational and employment opportunities to a wider range of people.

Three months ago in December 2019, the Rwandan Development Board (RDB)—responsible for overseeing business registration, foreign investment, and economic development planning—launched the Huye Employment Service. This project is a government initiative seeking to provide job placement to 1.5 million Rwandans by 2024. Specifically, the government wants to improve the linkage between unemployed people in remote areas and employers by providing access to job search tools, professional training, and help with job placement. Through the initiative, the government addresses inequalities in employment by helping women, youth, and vulnerable workers (workers with limited mobility) in secondary cities.

Other actors include local NGOs and cooperatives who create job opportunities by investing in community life. This is the case of the Nyamirambo Women’s Center (NWC), an NGO formed in 2007 by 18 women who wanted to address gender-based inequality and discrimination in the job market. Six years later, the women started a clothing line called Umutima (“heart” in Kinyarwanda). In addition to selling various items, they provide vocational training to women by teaching them how to decorate and make the accessories. Besides the clothing line, the NWC also provides cooking classes, tourist tours and expeditions in Nyamirambo, free literacy classes, and education promotion. Through its activities, NWC is not only enriching the community, but empowering women as well.

It’s undeniable that the job opportunities in Rwanda are scarce. The natural economic constraints in Rwanda—a small, landlocked country with limited natural resources—justify the need to promote local creative and entrepreneurial initiatives all the more. The goal is not simply to diversify the economy, but to create an economy for all Rwandans, by all Rwandans—with the true purpose being to enrich everyone. As Rwandans say: “Abashyize hamwe ntakibananira”; “for those that stay together, nothing can be insurmountable.” Since we have once chosen to stay together, now is a time to fight for each other and build the thriving and united society we promised to become.

To protect the identity of individuals, certain names and locations have been modified.

Edited by Nikita Buchko