The King of Queen’s Park

How Ontario Premier Doug Ford Used his Constitutional Powers to take Revenge on the city of Toronto

On October 1, 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada issued a 5-4 ruling in favour of the Ontario government’s Bill 5, a law that cut the size of Toronto’s city council from 47 to 25 seats in 2018. The Court’s decision, though narrow, definitively ended a years-long legal battle between Queen’s Park and Toronto City Hall. For Toronto mayor John Tory, local advocates, and a slew of city councillors, the ruling was a belated legal defeat to a fight they technically lost three years earlier. But for Premier Doug Ford, it was both a victory and a vindication of his controversial bill: “It’s the best present I’ve ever given the mayor,” he boasted about Bill 5 in response to the news.

The Toronto municipal elections were already underway in the city’s 47 wards when on July 27, 2018, the newly elected Progressive Conservative government passed Bill 5. This had the effect of nearly halving the number of council seats to 25 in the race, and aligned the boundaries with provincial and federal districts. The legislation was unexpected and uncalled for: no one had lobbied for fewer seats, much less while the election was underway. Yet the repercussions were far-reaching, forcing hundreds of smaller, first-time candidates and grassroots activists to drop out of the race, unable to marshal the resources needed to campaign in a territory twice as large. Bill 5 was met with fierce opposition from all corners of the city. Editorials and civic organizations decried how the bill would deal a severe blow to Toronto’s civic life and cost the city’s myriad of cultural and ethnic communities hard-fought gains for political representation.

For the Premier, the move was all about ‘streamlining’ City Hall: Ford, a veteran of City Hall, claimed that with fewer representatives around the table, the city would be less deadlocked and more decisive. As an added perk, the city would also save $5 million with 19 fewer councillors on its payroll.

Still, the notion that a leaner council works better is, at best, a fundamental misunderstanding of what municipal government typically is. Sure, city councillors like MPs and MPPs are meant to represent their constituents’ interests in government; but municipal issues are much narrower and more concrete. They can be as specific as amending a bylaw for a resident’s backyard renovation or negotiating with local businesses about adding a bike lane on a commercial street. This level of government deals the most with individuals and day-to-day issues. Doug Ford’s own brother, late Toronto Mayor Rob Ford, thrived in such an environment: he was known to give out his phone number to anyone who asked and took calls from constituents at all hours of the day. However, this roll-up-your-sleeves style of politics that the brothers trademarked as councillors is simply impossible to scale up.

The bill took a beating in the realm of public opinion, but the battle that mattered took place in the courts. The City of Toronto first submitted an appeal of Bill 5 to the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, arguing that the legislation went against section 2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights for violating candidates’ and voters’ freedom of expression, as well as Section 3 of the Charter, claiming a lack of adequate representation. That Court sided with the city, but Ontario’s Attorney General applied for a stay on the Superior Court’s decision pending appeal, requiring the election to proceed with 25 wards rather than 47 – making the city’s legal attempt at overturning Bill 5, at least in practical terms, useless. The election would proceed on the province’s terms, not the city’s. Then, in a 3-2 split decision on September 19, 2019, nearly a year after the election, the Court of Appeals sided with the province, overturning the Superior Court’s decision, stating that its application of sections 2(b) and 3 of the Charter was too broad for Bill 5. The city appealed, and the legal battle ultimately reached the Supreme Court in March 2021 – nearly three years after the municipal election. It is there that the Justices narrowly and finally dismissed the City of Toronto’s appeal in October.

From a logistical perspective, the Supreme Court’s majority opinion found that Bill 5 had not limited freedom of expression because it gave candidates sufficient time to re-orient their campaign and re-register before the election took place. Yet on a more fundamental level, the Court ruled that the right to effective representation only applied to federal and provincial elections; the Charter’s protections, then, did not apply to municipalities. The Court further ruled that “unwritten constitutional principles,” such as the ‘principle of democracy’ would not be enough to override provincial authority. In the end, critics could call the bill many words — abrupt, irrational, bewildering — but only one word mattered to the province: constitutional.

The ruling revealed a sobering but perhaps misunderstood reality about political power in Canada: the Constitution does not define nor protect municipalities. They are creations of the provinces and are thus dependent upon and at the mercy of provincial leaders. The Supreme Court demonstrated that a province could rejig the districts of a city at a whim, regardless of any pushback by the people affected by it.

But to make Bill 5 a debate about constitutionality was always an afterthought to the real issue at hand. In fact, legality barely mattered at all, as the Premier vowed to use the Charter’s notwithstanding clause, which allows the provincial government to override some constitutional rights before the bill had ever been challenged in court. Instead, the Supreme Court decision gave legal credence to a long-standing personal vendetta the Premier has had against the city of Toronto.

In the early 2010s, the Ford brothers were pariahs in City Hall: they were disparaged as reckless, incompetent, and clueless outsiders who distracted from the usual humdrum of competent but dull bureaucrats. What had started as a matter of local bickering took on epic proportions when a video surfaced of mayor Rob Ford smoking crack cocaine. Suddenly the whole world was paying attention to the mayor’s antics. Video recordings of late-night “drunken stupors,” mercurial and childish conduct before council and an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel all kept him in the spotlight. The stories that filled tabloids added to growing calls from outraged councillors that the mayor was unfit to govern – all the while, his brother stood by his side and tried in vain to defend him. The City Council ultimately voted to transfer his mayoral powers to Deputy Mayor Norm Kelly – a move Doug decried as “undemocratic” – so that he was a mayor in name only. Doug replaced his brother on the mayoral ticket in late 2014 after Rob was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, but finished second in the election. With Rob’s death in 2016, ‘Ford Nation’ had been written off as a hectic though short-lived phase of Toronto’s city politics.

But the stars quickly re-aligned for Doug: a sexual misconduct allegation forced Progressive Conservative leader Patrick Brown to resign, allowing Ford to snatch the party’s leadership months before an election against a historically unpopular Liberal government. When he was finally elected Premier with a large majority, the passing of Bill 5 made his revenge swift and sweet.

Never mind that the cost savings never materialized, or that years of municipal consultations had pegged 47 as the ideal number of seats for the city council. Imagine the satisfaction of watching Josh Matlow and Joe Mihevc – two well-established downtown city councillors and long-time foes of the Ford brothers – being forced to exchange blows in their newly amalgamated district. In this case, why fight your enemies when you can rewrite the rules so that they fight against each other?

The Bill 5 debacle might not mean much in the long run. The number of seats in the Toronto city council will probably be restored the next time an NDP or a Liberal government is elected, and historians will write it off as what it was: a shrewd and petty act of revenge. But what the bill has shown is that there are easily exploitable gaps in our Constitution that enable leaders to act without the level of accountability we have come to expect from democratic institutions. When a Premier can sign pernicious legislation into law without even a slap on the wrist, perhaps it is time to reconsider the rights of municipalities within our Canadian confederation.

Doug Ford might have finished a far second in his run to become mayor of Toronto, but his election as Premier highlighted one crucial question about power in the city: why settle for mayor when you can rule like a king?

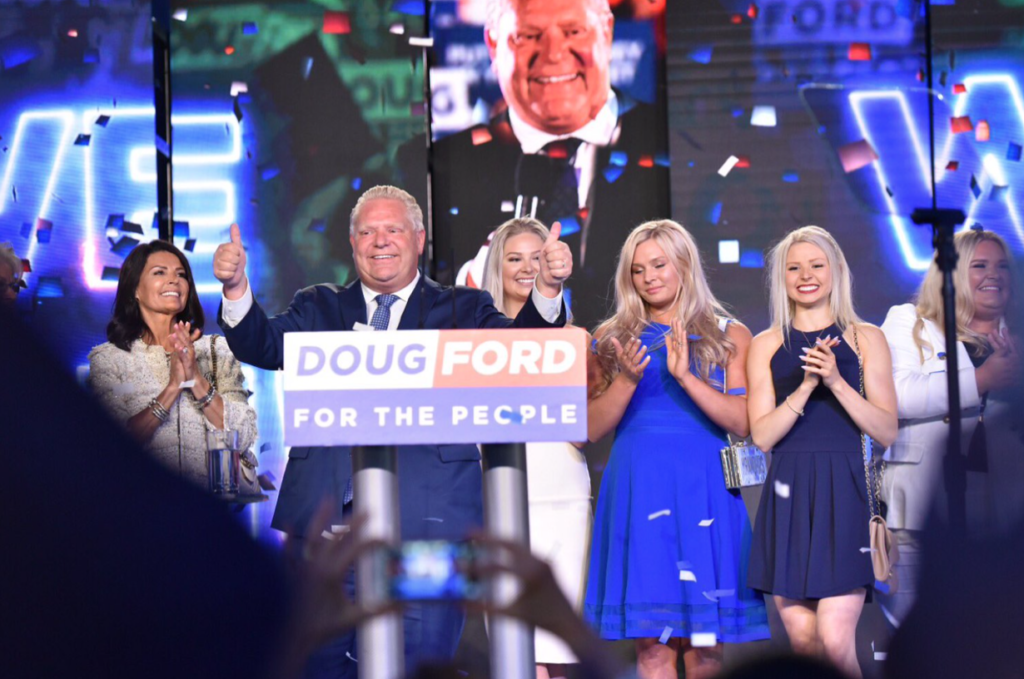

Featured image: “Doug Ford Protests” by Eric Parker is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Teresa Tolo