The Nationalist Challenge to the United Kingdom

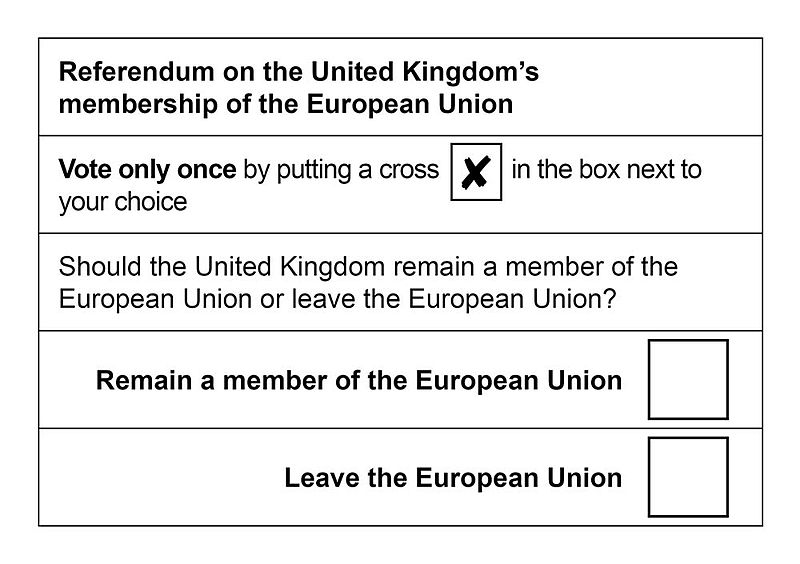

Credits: https://www.publicdomainpictures.net/pictures/190000/nahled/brexit-referendum-uk-1468255044bIX.jpg

Credits: https://www.publicdomainpictures.net/pictures/190000/nahled/brexit-referendum-uk-1468255044bIX.jpg

Neither Scotland or Wales seem to be content members of the United Kingdom (UK) at present, as both nations have recently seen a surge of independence sentiment. At its 2019 annual party conference, the Scottish National Party (SNP) declared its intentions to ask the UK Government for permission to hold a second referendum on Scottish independence next year. In Wales, the new leader of Plaid Cymru (the Party of Wales) has called for a referendum on Welsh independence to be held before 2030. A major cause of this resurgence is anger over the UK’s failure to consult either nation over Brexit, which will have undeniable effects on both Scotland and Wales. However, supporters of Scottish and Welsh independence desire significant majority support for their cause among the population before calling for independence referendums to be held. The upcoming December 12th UK General election offers nationalists the opportunity to increase support for independence and translate surging independence sentiment into electoral gains. The General election also offers a chance for the two parties likely to form the next government, the Conservative Party and Labour Party, to address Scottish and Welsh concerns over Brexit, and tackle the resurgence of independence sentiment.

The UK’s constitution

The nature of the UK’s constitution presents a long-term structural problem, as the UK Government is not legally required to consult Wales and Scotland in matters of governance. In 1997, Scottish voters and Welsh voters, by means of a referendum, voted for the establishment of a Scottish Parliament and a Welsh Assembly. The UK Parliament decided to devolve some of its powers to the new Welsh Assembly and Scottish Parliament, in order to provide the nations with some degree of self-governance. As both bodies along with the Northern Ireland Assembly were granted their powers via devolution, they are collectively referred to as the devolved assemblies.

The key principle upon which the UK’s largely uncodified (unwritten) constitution is based is parliamentary sovereignty. This provides the UK Parliament – as the supreme body in the country – with the ability to legislate on any matter it wishes. Due to parliamentary sovereignty, the powers of the devolved assemblies are not constitutionally protected: the UK Parliament reserves the right to take back devolved powers. A key constitutional principle governing devolution is the Sewel convention, under which the UK Parliament is required to ask for permission from the devolved assembly before legislating on devolved powers. However, as conventions are not legally binding, the UK Parliament can ignore the Sewel convention without legal repercussions.

A tale of two referendums

An early wave of independence sentiment occurred in 2011 when the SNP won a majority in the Scottish Parliament elections, an impressive feat given the mixed-member proportional representation system that is used. The SNP had campaigned on promises of a Scottish independence referendum and the UK Government eventually agreed, believing it could win any referendum and settle the question of Scottish independence for a generation. The referendum was held three years later, in 2o14, and the Scottish electorate rejected independence with 45% in favour and 55% against. A major reason behind the result was a fear that an independent Scotland would be unable to join the EU, as Spain would veto Scotland’s application to avoid encouraging Catalonian separatists. Following the referendum, the question of Scottish independence was assumed to have been settled for a generation, or until there was a significant change in Scotland’s relationship with the UK Government.

With the question of Scottish independence seemly solved by a referendum, Conservative PM David Cameron thought a referendum could deal with the issue of rising euroscepetic sentiment. He held a UK wide-referendum on EU membership in 2016 and it backfired on Cameron, as the electorate decided to leave the EU. The vote was split along national lines with Scotland and Northern Ireland voting to remain in the EU while England and Wales voting to leave. This resulted in a significant change in Scotland’s relationship with the UK Government and in the vote’s immediate aftermath, the SNP government began to press for a new Scottish independence referendum.

Shaping or not shaping Brexit

The UK Government could have consulted the Scottish and Welsh Governments over Brexit in order to appease both assemblies but they didn’t. The first chance came in 2017, when the UK Government sought to activate Article 50, the legal process for leaving the EU. The devolved assemblies took the UK Government to court to determine if their approval was needed for Article 50 to be activated. The case reached the Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled that the the UK Government did not need the consent of the devolved assemblies. The Supreme Court justified this ruling by stating that the power over foreign policy is reserved to the UK Parliament. The Welsh Assembly and Scottish Parliament, using purely symbolic votes, as the Supreme Court ruling forbid binding votes, voted to reject activating Article 50.

Although the UK Government is not constitutionally required to consult the devolved assemblies, for the sake of maintaining good-faith relations, could have chosen to consult, yet it didn’t. The Conservative Party, which currently holds a minority Government, has chosen to pursue a hard-Brexit. Under a hard-Brexit, the UK would cut most of its ties to the EU, by for example, leaving the EU Single Market and the Customs Union. Yet, both the SNP government and Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition government of Wales, favor a soft-Brexit, under which the UK would retain close ties with the EU. The European Research Group (ERG), an internal eurosceptic Conservative Party caucus, rejects a soft-Brexit and has proved unwilling to compromise given the power they hold in the minority parliament. Therefore, the UK Government rejected consulting the devolved assemblies to avoid risking its stability. As a result, this has lead to a resurgence of independence sentiment as it appear to many in Scotland and Wales that, only through independence, will both nations be able exert control in shaping their relationships with the EU and their futures more generally.

Implications

As Brexit represents a significant change in Scotland’s relationship with the UK Government, the SNP has stated its intentions to hold another independence referendum next year. However, an independence referendum requires the permission of the UK Government, which is unlikely to be forthcoming as the Conservative Party supports the continued maintenance of the Union. The Conservatives currently have a minority government and have called an election to win a majority. Polling for the upcoming December 12th UK general election suggests that no-party is likely to win a majority partly due to the SNP being forecast to win nearly all of Scotland seats. The SNP would be in the position of kingmaker and could exchange its support for an independence referendum. The Conservatives are opposed to a second Scottish independence referendum. However, their main opponent Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour party leader, has suggested he would be receptive to a second Scottish independence referendum.

Polls show there is a small majority that opposes Scottish independence, which could be overcome in a referendum. However, the 2016 referendum on EU membership only produced a small majority in favor of leave and no consensus over the shape of Brexit. As a result, this has allowed those opposed to Brexit to assert that the 2016 referendum does not represent the final will of the UK population. This assertion has allowed opponents of Brexit to delay UK Parliament from passing a withdrawal deal on the terms of exit from the EU and even try to overturn the result of 2016 EU referendum. An independence referendum producing a small majority in favor would likely be similarly challenged and, as a result, the implementation of independence would be resisted by the opposition. Therefore, the SNP seems prepared to wait until the polls show a significant majority in favor of independence before requesting a referendum. That will take time; however, should the UK Government continue to alienate Scotland, the time may come sooner than expected.

Welsh independence does not enjoy the same level of support as Scottish independence. In a recent poll, only 33% supported Welsh independence while 48% opposed. However, 33% does represent a dramatic increase compared to previous years. Polling for the next Welsh Assembly election, which is due in 2021, shows that the pro-independence Plaid Cymru may overtake the pro-unionist Labour Party as the largest party in the Welsh Assembly. Even if Plaid Cymru does not win the 2021 election, the polls show its support would be necessary for another party to form a government. Plaid Cymru’s support could be traded for a Welsh independence referendum or a push for more powers for the Welsh Assembly. However, it does not appear that the surge of independence sentiment will benefit Plaid Cymru at the upcoming December 12th UK General Election with polling suggesting the party will only maintain the three seats it already holds. Plaid Cymru may be able tap into growing independence sentiment, thereby improving their polling for the next Welsh Assembly election in two years time, however they still have a lot of work to do.

Tipping point

At the moment, neither Welsh nor Scottish independence enjoys the overwhelming support of the population of their respective nation. The need for overwhelming support is currently the only thing holding back Scottish independence, while support for independence in Wales has not yet reached critical levels. The UK Government is unlikely to tackle the long-term structural cause behind rising independence sentiment any time soon since the UK Government is not constitutionally required to consult the devolved assemblies. The UK Government can use the December 12th UK general election to change course over Brexit, by bringing the devolved assemblies into the conversation and giving special treatment to Scotland and Wales. However, given the UK Government has consistency refused to change course and consult the devolved assemblies over Brexit since 2016, they will likely refuse the opportunity offered by December 12th.

Featured Image. “brexitttt.jpg” by Public domain pictures, licensed under Public Domain

Edited by Rebecka Eriksdotter Pieder