The Ongoing Struggle for National Accountability in Latin America

It is no secret that Latin America was imperially occupied for centuries. Even following the revolutions and gradual decolonisation in the early 20th century, the nations located between the northern border of Mexico to the southern horn of Argentina were plagued by external intervention. The United States’ interventionist Cold War policies which sought to deter communism’s contagious spread placed developing Latin America in the superpower’s crosshairs. Through experiments in political influence and military coups d’états, the American government imposed a “democratic” agenda—everything from hand-picking heads of state to backwater operations such as the U.S. Army School of the Americas, designed to train Latin American troops in guerrilla warfare and torture to enforce American interest in the region.

Even though the days of Augusto Pinochet and Manuel Antonio Noriega’s totalitarian regimes have come to a close, the region is still recovering from the policies they represented. After years of an absence of punishment for violent and corrupt Latin American leaders—who were protected in the name of greater American interests—a pattern was established. Corruption became commonplace and persists to this day, as well as bribery and political violence. The cases of El Salvador and Venezuela show us that every democracy is in danger of backsliding into authoritarianism. And yet, political punishment is beginning to be enacted where necessary.

On February 10th, 2020, Rafael Correa’s prosecution commenced on the basis of an investigation that began in May of 2019. Ecuador’s ex-President is accused of embezzlement, censorship, and corruption with upwards of 30,000 USD disappearing during his 2007-2017 time in office. Ecuadorian media censorship and kidnappings ordered on Colombian soil reinforce Correa’s reputation as an autocrat. The trial is currently ongoing in absentia as Correa fled to Belgium. Publications like The Economist see a pro-democratic ruling as a step toward the end of political and financial abuses. Previous examples, however few, do exist.

In 2009, Alberto Fujimori, who ruled Peru from 1990 to 2000, was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment on the basis of crimes against humanity. He had been previously sentenced to six years for ordering an illegal search while in office. Following his resignation in 2000, the trials went smoothly, despite the complication of his absconding to Japan. Fujimori’s defining moment was the 1992 autogolpe: a notorious coup on his government while he was in office, used to circumvent Congress during the ongoing terrorist violence and consolidate his power as a dictator. Common under Fujimori were kidnappings and killings justified within a stringent anti-terrorist environment of curfews and wiretaps. Violators were often punished with death. His unchecked power flowed easily into his security forces who often valued bribes over their duties as law enforcement. Fujimori’s actions may have contributed to putting an end to the violence of Sendero luminoso (Spanish for “Shining Path”)—Peru’s radical communist party and terrorist organization—but he did so by overstepping his powers as an elected official. Indeed, persecution any number of years after such crimes may not actively hold leaders responsible for their offences but it may herald the reinstitution of checks and balances.

While Fujimori’s charges of violence and unconstitutionality are quite different from the imputations against Correa, they both stem from an abuse of executive power. After years of crimes committed and pardoned by Latin America’s heads of state—a remnant of American “no-questions-asked” policy in the hunt for communist insurgency—trials such as those of Correa and Fujimori, when successful, shatter the assumption of impunity. Steps toward punishing abusive leaders can lead to a reduction in political and financial crimes, while increasing the accountability of democratic officials to their constituents through democratic consolidation.

Democracy is, after all, an exercise in accountability. The public raises officials to power on a mandate they must follow to retain their power. Otherwise, they are punished politically through elections and referendums. A leader should not exist outside of the law, and that is a principle we can now see solidifying in some Latin American states. Nevertheless, entities like Brazil’s Odebrecht corporation—an international construction firm responsible for bribery across Latin America’s governments in exchange for contracts—still plague Latin America’s private and public spheres with bribery and rentierism. According to the Wall Street Journal, the scandals surrounding Odebrecht alone involve twelve countries, over 800 million USD in bribes, and upwards of three billion USD in profits for the corporation between 2001 and 2016. In Peru, according to the Peru Telegraph, the last five Presidents have either been accused, sentenced to prison or committed suicide on account of their Odebrecht ties.

This is not to say that corruption and abuses of power must define the region. In the case of Ecuador, Correa’s undoing was enacted by his former right-hand man. Lenín Moreno, Ecuador’s current President, was formerly Correa’s Vice President. Since turning on his superior and winning the presidency, Moreno has devoted his time in office to dismantling the corrupted architecture of Correa’s regime which allowed him, along with the exploitation of his political powers, to go unpunished for so long.

Moreno, however, is not Ecuador’s most popular president, as some of his policy changes have caused economic turmoil in many sectors and a decline in the GDP: insubordination is a constant threat. It is Latin America’s fragile resource-dependent economies that have warranted intervention before, and could trigger it again should Correa’s trial end in the defendant’s favour. It is worth remembering that a US-backed military coup created Pinochet’s Chile in the midst of severe economic decline under Allende, Chile’s previous president. Money usually comes first, even in democracies, but a successful trial that further discredits Correa could potentially lead to another wave of popular support for Moreno.

Nowadays, being a democracy is no longer the exception. The public holds the power to shape the system they live in and choose the political leaders they deem fit. While it is undeniable that corruption and violence are still present in the region, we could see more political systems accountable to the publics’ interests and democratic values if nations continue to make criminal leaders face them. Apart from Correa’s trial, Pinochet’s referendum and Fujimori’s imprisonment, increasing accountability can be signalled by peaceful transitions of power in elections as Latin American states approach more democratic and, by implication, accountable regimes, hopefully leaving the days of populism, authoritarianism and their corrosive side effects behind.

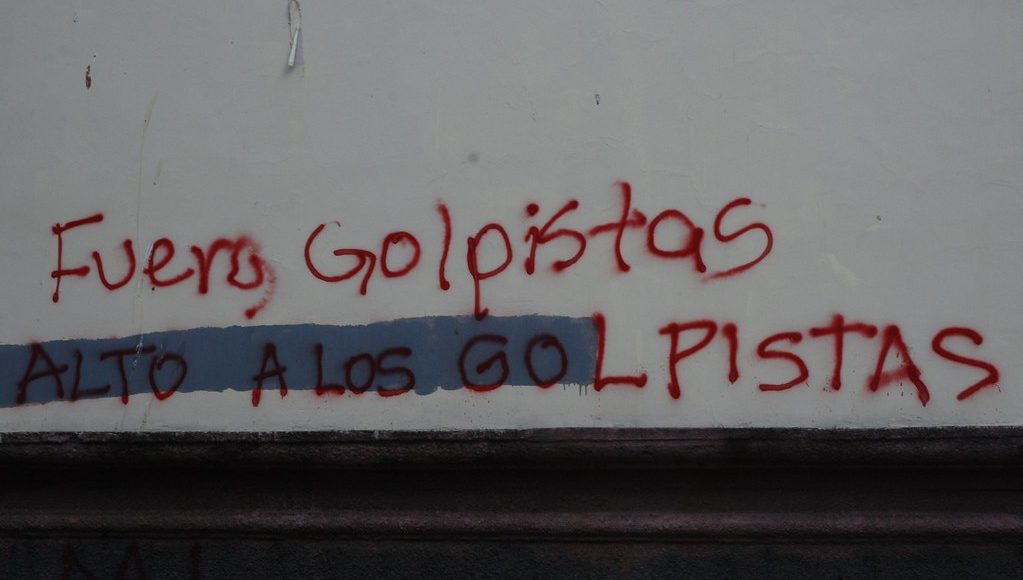

Featured Image: Graffiti in Tegucigalpa, Honduras begging for political violence and constitutional violations in Latin America to stop. Translates to “Out golpistas/stop the golpistas.” “Golpista” is the Spanish word for a coup d’état or its executor. “DSC_0971” by Celine Massa is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Edited by Angello Alcázar