The Opioid Crisis: A Canadian Perspective

Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alley_Graffiti_-_Dead.jpg

Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alley_Graffiti_-_Dead.jpg

The Opioid Crisis plaguing the United States is no new phenomenon, having become a familiar and persistent headline. However, 2019 has brought an onslaught of lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies for their roles in creating and intensifying the crisis, offering a glimmer of hope that they may soon be held accountable. In a landmark case on April 23, the Rochester Drug Cooperative became the first company to face “federal criminal charges… for conspiring to illegally distribute opioids,” settling the case at a cost of $20 million. Two months later, Insys Therapeutics Inc became the first pharmaceutical company to go bankrupt after settling investigations into schemes of bribery and other illegal practices “to induce doctors to prescribe highly addictive opioids.” The substantial settlement was valued at $225 million. And on August 26, an Oklahoma judge ordered Johnson & Johnson, who “marketed opioids for years in a way that overstated their effectiveness and underplayed the addiction risk,” to pay $572 million for its role in stimulating the state’s opioid crisis that has already killed thousands. Most recently, Purdue Pharma, a producer of the opioid Oxycontin, filed for bankruptcy as a result of a $12 billion settlement deal that also required the Sackler family, who had controlled Purdue Pharma over the course of the crisis, to cede control of the company.

While the American opioid crisis has garnered significant attention, opioid abuse is by no means a uniquely American calamity. Although opioids are “the second-largest class of pharmaceutical substances across the globe after cancer medicines,” they are considered by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime as “the most harmful class of drugs in the world.” Meanwhile, nearly 95% of global opioid use occurs in the US, Canada, and Western Europe.

Canada currently faces an opioid crisis of its own; one of the same magnitude and severity as the United States. Taking the lead on holding companies accountable even before the United States, British Columbia, who declared a public health emergency in 2016, sued a myriad of opioid producers for their contributions to the province’s epidemic on August 29, 2018. In light of Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy declaration, also named in B.C.’s lawsuit, the province continues to pursue legal action and compensation. Ontario similarly launched its own class-action suit against a number of pharmaceutical companies this past May.

The Canadian Crisis

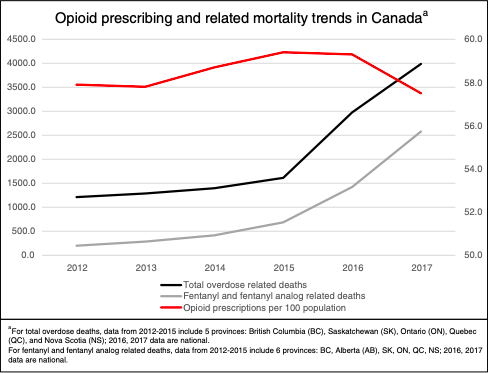

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, opioid sales for prescription to Canadian hospitals and pharmacies have increased by over 3000% since the early 1980s. Presently, Canada is the second highest per capita user of opioids globally, after the U.S. By 2008, prescription opioids had become “the fourth most prevalent form of substance use,” becoming more abused than heroin or cocaine. Meanwhile, opioid prescriptions “increased from 10,209 defined daily doses (DDD) per million population/day in 2001-2003 to 30,540 in 2012-2014. “ Such a rise in opioids’ prevalence can, at least in part, be attributed to the pursuit of aggressive marketing strategies by pharmaceutical companies in conjunction with the “changing culture of pain management.” Alarmingly, B.C. and Ontario experienced a 10-fold increase in the number of individuals enrolled in opioid treatment programs between 1996 and 2014, from less than 6000 to 60,000 between the two provinces. Opioid-related deaths continued to rise considerably in the decade between 2005-2015, mostly as a result of prescription opioids.

In the years after, from 2016-2018, there were 11,500 apparent opioid-related deaths, 94% of which were deemed accidental or unintentional. The rising number of deaths coincides with significant upsurges in opioid-related hospitalizations, which “more than tripled between 2011-2012 and 2016-2017.” Notably, “smaller communities are experiencing opioid poisoning hospitalization rates that are more than double those in Canada’s largest cities.” However, the recent rise in overdose deaths have, in large part, been attributed to “the rising prevalence of highly potent synthetic opioids, such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl,” primarily from China, though Mexico and India have also emerged as sources of the drug. Still, despite the mounting number of deaths resulting from street drugs laced with fentanyl and its analogues, Judy Darcy, B.C.’s Minister of Addictions and Mental Health, the first (and, as of now, only) minister of her kind, asserts that many addictions began during a period “when prescription opioids were being aggressively marketed,” which may have turned these individuals towards streets drugs, though these statistics are unattainable.

Past Responses

Within the Canadian context, significant attempts to respond to the growing opioid crisis began in 2010. In that year, the National Opioid Use Guideline Group offered recommendations regarding the practice of opioid prescription in Canada, however these recommendations continued to support the prescription of opioids and provided no guidance as to “when not to prescribe or when to limit doses or durations.” Two years later, oxycodone became associated with a substantial amount of “opioid-related harms and deaths,” causing provinces to take the drug off their drug formularies and a decrease in its prescription. However, what followed as a result was an increase in the prescription of other opioids instead. In 2013, Ottawa released a national strategy aimed at “reduc[ing] the harms associated with prescription drug misuse… [and] included a large list of recommendations across different streams of action,” with no substantial effect on opioid-related harms. What followed in 2015 was an attempt by federal regulators to enforce methods that would prevent the falsifying and tampering of opioid prescriptions. Nonetheless, these regulations failed to encompass all opioids, not to mention tamper-proofing efforts have been found to be only mildly effective in reducing opioid misuse. More recently, Canadian health authorities have promoted an increased accessibility to naloxone, a drug that counteracts the effects of opioid overdoses, along with “more supervised consumption facilities and opioid-maintenance treatment.”

Ultimately, however, all these efforts have failed to stop, or more cynically even mitigate, the growth and magnitude of the crisis. As noted by a group of scholars in an analysis of Canadian policy responses to the issue, “[a]lthough aggressive marketing efforts by pharmaceutical companies and training deficiencies among medical professionals may have contributed [to the increase in opioid availability], they occurred in regulatory environments that permitted such developments.”

Each Party’s Planned Response to the Crisis

With the scale and scope of the Canadian opioid crisis reaching every part of the country, it is evident that whoever emerges triumphant in the upcoming federal election will need to act with a real sense of urgency. While individual MPs from within each party may have varying opinions, the parties can be seemingly organized along a spectrum of viewpoints and ideologies regarding the crisis.

The Conservative Party

Though the Conservative electoral platform has yet to be released, what the party has stated regarding the crisis appears to lean toward more traditional responses, therefore occupying one end of the spectrum concerning party approaches. The party has evoked support for a focus on the cracking down on the supply of drugs by increasing mandatory minimum sentences for drug traffickers, as well as placing an emphasis on “helping Canadians struggling with addiction through recovery and prevention,” though there are no specifics on what recovery and prevention might entail. And although the party states it has star candidates who are supportive of legalization and decriminalization, the party as a whole remains staunch in keeping hard drugs illegal. Notably, party leader Andrew Scheer has been vocal about the need for Canada to “hold China accountable” for their role in supplying illicit fentanyl. Moreover, Scheer has been critical of the primacy given to harm reduction strategies that have been promoted in the face of the crisis, stating that they do not “break the addiction cycle.”

If the previous Conservative government under Stephen Harper is any indication for how a Scheer-led Ottawa may handle the crisis, then we can expect little funding towards the research and administration of harm reduction programs. Should this become a reality, Gillian Kolla, a harm reduction worker and public health researcher at the University of Toronto, states that it “would be directly leading to preventable lives lost.” Although it may be a useless exercise to compare the previous Conservative government to a potential Scheer-led one, his criticisms of harm reduction strategies, such as safe injection sites, is cause enough to consider this possibility.

The Liberal Party

While the Liberal Party is yet to release a specific electoral platform on the opioid crisis, they have maintained the most centrist position on the crisis relative to the rest of the parties. Although officially the party maintains a stance that it would not decriminalize or legalize hard drugs (though advocates assert that to do so “is necessary to properly curb overdoses and the tainted drug supply”), the Liberals’ Health Canada has been fairly progressive over the course of Justin Trudeau’s tenure. Notably, the Trudeau government “[eased] the federal restrictions around opening supervised consumption sites and [enacted] legislation that provided some legal protections for people who called 911 during an overdose.” Furthermore, national-level data on overdoses deaths began to be gathered for the first time while “a one-time ‘emergency treatment fund‘ for provinces and territories to provide ‘evidence-based’ treatment” was established. Additionally, prescription heroin became approved as possible treatment for adults with chronic opioid disorder. Still, while these measures may have been steps in the right direction, it may be necessary to begin taking more drastic action, considering the current reality of the crisis.

The NDP

Occupying the other end of the spectrum, along with the Green Party, the NDP have dedicated an entire section of their electoral platform towards alleviating the opioid crisis. Notably, the party would declare the crisis a public health emergency and work “to end the criminalization and stigma of drug addiction.” According to Kolla, this declaration would show a commitment of federal resources towards battling the problem. An NDP government would “combat the opioid crisis through funding for addiction and mental health services” and work with provinces to support supervised consumption sites and increase readily available treatment for those struggling with addiction. Moreover, party leader Jagmeet Singh has been outspoken concerning his desire to take federal legal action against pharmaceutical companies for their roles in creating, and exacerbating, the opioid crisis in order to force them to compensate the “public costs” that the issue has generated.

The Green Party

Similar to the NDP, party leader Elizabeth May has stated that she would declare the opioid crisis a public heath emergency as well as legalize heroin and other opioids. The Green platform regarding the opioid crisis promises to advocate for a safe supply of drugs and an increase in funding for drug testing and naloxone kits.

Where We Go From Here

While legal action against numerous pharmaceutical companies throughout this year provided hope that those responsible, at least in part, for the opioid crisis would be held accountable, it is fair to wonder whether this represents anything more than moral victories. Although Johnson & Johnson settled their case, the amount is less than one percent of the company’s annual sales. Meanwhile, it is being alleged that in recent years, the Sackler family has been transferring their wealth to safe havens outside of the jurisdiction of the American justice system for this very scenario. Compounding this issue, critics of the Purdue deal claim the payout “will not reach close to the $12 billion mark and… the company won’t be found liable by a jury or judge.” Perhaps most startling, Insys Pharma, who declared bankruptcy just two months ago, received FDA approval to produce naloxone, providing them the ability to profit from the crisis that they helped create (thought they are not the only pharmaceutical company to take advantage of this opportunity). Facing this reality, it remains disheartening that corporate greed of this magnitude simply gets another slap on the wrist.

Domestically, it is clear that the opioid crisis is a national problem. Whichever party assumes power after the elections in October will immediately face a daunting challenge. However, experts have provided possible policies that could spark the beginnings of a resolution to the crisis, such as more stringent regulations and monitoring systems surrounding prescription opioids, both in terms of dosage and duration, and “establish[ing] an appropriate national surveillance for opioid-related harm indicators (a standard practice in other countries).” Moreover, while the pharmaceutical companies contributed their fair share to the crisis, medical professionals must similarly be held accountable (as they are in the United States) to responsibly prescribe opioids to patients who legitimately need them.

Fuelled by greed and negligence, the opioid crisis is a reality that all Canadians must face. The past of stigmatizing and marginalizing people struggling with addiction has provided nothing but a perpetuation and intensification of the problem. Beyond the statistics, the opioid crisis has indiscriminately destroyed lives and stolen loved ones. Coming from Vancouver, where drug addiction is something that has become so commonplace, I realize it can be easy to become numb to its realities and effects and to distance oneself from it, relegating it as someone else’s problem. It becomes so much less of a personal and moral burden for the issue to remain something beyond each of us. At this point though, the crisis can no longer be seen as an addict’s problem; rather, in order for it to be truly resolved, the problem needs to become a Canadian one.

Edited by Clariza-Isabel Castro