The Other Side of the Miracle on the Han River.

Sout

Sout

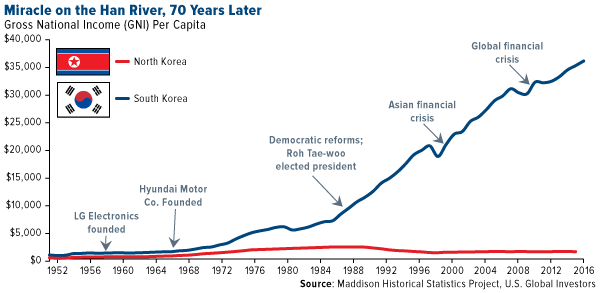

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) is hailed as a model of successful economic development, experiencing stunning economic growth during the 60s and 70s in an era termed the Miracle on the Han River. The era of growth transformed South Korea from one of the poorest states on Earth to its current status as the eleventh largest economy on Earth.

Much of this growth is attributed to the actions and policies of the South Korean developmental state, as it embarked on policies which promoted export-oriented industrialization. However, a closer examination reveals a darker side to the developmental state, i.e. labour repression by an authoritarian regime which runs contrary to human dimensions of development. In doing so, it reveals the tensions between state-centric economic development policies and that of human rights.

The Developmental State

To begin with, the developmental state is a theory of economic development based on the experiences of the industrialized countries of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. The theory arose as a response to neoliberal economics, which sees the state as the central cause of underdevelopment and thus urging for a limited role of the state in successful economic development. Instead, the developmental state posits that the state is a central actor in resolving underdevelopment, and argues that state economic policies must be rooted in economic markets.

The state is the central actor in the theory of the developmental state, as it is responsible for defending and advancing the public good. The public good is defined by the bureaucracy, a state apparatus composed of national elites who define the social, economic, and political agenda of the state’s national interests. This, in conjunction with the order and stability created by the state’s monopoly on power (state holds the monopoly on military power, judicial power, etc), creates a stable foundation for economic development to occur. State sovereignty fundamentally aligns with the theory of the developmental state: centralized sovereign states are the central actor which promotes successful economic development.

The developmental state is characterized by the concept of embedded autonomy, in which bureaucrats appointed by meritocracy, with a high level of corporate coherence, are insulated from the rest of society, thereby permitting the bureaucracy to pursue developmental policies aimed to provide and enhance public goods without significant domestic interference. The developmental policies relate to the concept of export-oriented industrialization, which refers to policies designed to develop a country’s economy through the production and exporting of goods in which the nation holds a comparative advantage. This requires the bureaucracy to ensure the success of their exports through currency devaluation and low production costs. Meanwhile, the bureaucracy responsible for developmental policies shares linkages with the private sector, thereby permitting the bureaucracy to ascertain the required and appropriate economic policies for successful development. Furthermore, the bureaucracy promotes exports through welfare enhancing policies: providing capital to large conglomerates, and the concept of administrative guidance, in which the private sector is guided into undertaking certain economic activities through state subsidies and assistance. Finally, most developmental states are characterized by the existence of a soft-authoritarian regime.

Soft-authoritarian regimes are defined as a political system in which there is a minimal component of democracy, and where basic social and political rights are compromised due to a strong state influence in all matters of daily life. In South Korea, the rule of law was replaced by a Neo-Confucian rule of virtue: the duty of the citizen is to consent to state policies, and in exchange, the state provides stability through economic development and the repression of domestic troublemakers. In addition, the duty of the citizen to the state is held to be more important than the state’s duty to its citizens. This then generates the fundamental tension between the developmental state and human rights, as economic development is prioritized relative to the development and protection of human rights. This derives from the unfortunate reality that soft-authoritarian regimes are not accountable to the public, therefore, developmental policies are determined by what the state bureaucracy determines is in its national interest. This generates government policies which can repress or exclude specific groups in society, for example, in the South Korean case, the government’s focus on cheap exports led to the repression of labour in order to maintain low labour costs. This issue is significant, as contemporary views regarding international development revolve around the concept of human development. Successful development of a state is more than the mere meeting of economic indicators and must focus on ensuring that the collective rights of citizens are protected and supported by the state.

Case Study: The Gwangju Protests

South Korea was one of the poorest states upon its independence in 1945, and remained so throughout the 50s under President Syngman Rhee. However, General Park Chung-Hee launched a successful coup d’état in 1963 and promised to lead the nation into a new prosperous era. This occurred through the formation of the developmental state in South Korea, and the state adopted policies of export-oriented industrialization which propelled the nation in an era of stunning economic growth termed the miracle on the Han river. However, such stunning growth reveals the tension between the developmental state and human rights, as economic growth was borne by the repression of organized labour and political repression of South Korean citizens, and ultimately climaxed in the massacre of hundreds of protestors during the Gwangju protests.

To begin with, Korea was annexed by the empire of Japan in 1910 and achieved independence in 1945 after the latter’s defeat by the allied powers during the Second World War. However, Korea fell victim to Cold War politics and was split along the 38th parallel in 1948 into two nations: North and South Korea. North Korea aligned with the Soviet Union and adopted socialist institutions, meanwhile, South Korea, led by President Syngman Rhee, aligned with the United States and adopted capitalist institutions. However, the government of President Rhee was plagued by economic underdevelopment, which was aggravated due to a lack of coherent economic planning by President Rhee. In addition, there was a fundamental absence of embedded autonomy within the major government bureaucracies: President Rhee utilized foreign financial assistance to bribe key ministers, and the bureaucracy was hired through a political basis rather than merit. South Korea’s continued economic underdevelopment under President Rhee generated significant political instability in South Korea, and led to a coup d’état on May 16th by General Park Chung-Hee, who promised to purify the government from corruption and lead the nation into a new prosperous era.

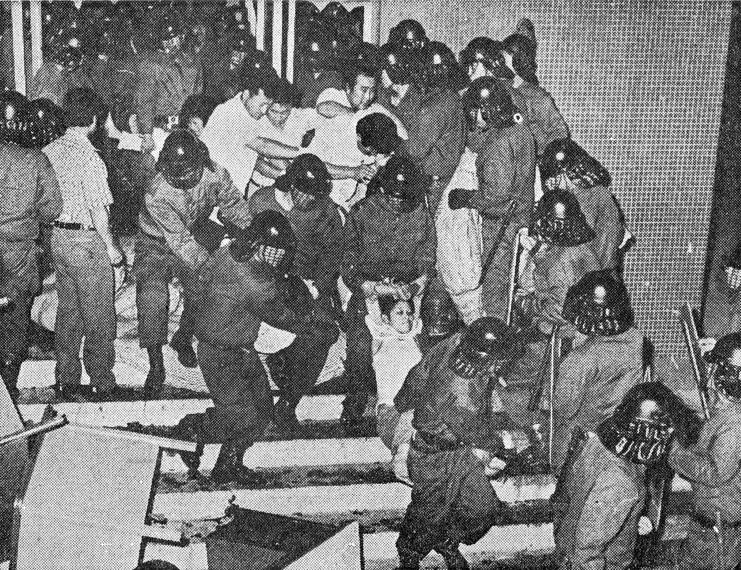

Retrieved from: https://tinyurl.com/yc93lfzj

General Park stayed true to his word and launched a series of economic and political reforms which bolstered economic development and consolidated state power. General Park emulated the Japanese model of the developmental state and created the powerful ministry of the Economic Planning Board [EPB]: a government institution imbued with high levels of embedded autonomy which propelled South Korea on a path towards economic development through a series of five-year plans. (plans highlighting the state’s economic policies). South Korea, with guidance by the EPB, adopted a policy of export-oriented industrialization. Substantial subsidies and loans were provided to chaebols, massive business conglomerations which, even after decades of economic diversification, comprised 67% of South Korea’s GDP in 2017. The chaebols focused on the exports of labour-intensive goods due to the dearth of capital and natural resources in South Korea, and this then generated the need for the chaebols to maintain low labour costs in order to maintain their competitiveness in the international economy. These policies were maintained by General Park’s successor, General Chun Doo-Hwan, who ruled South Korea from 1980 until 1987, when South Korea democratized due to country-wide protests calling for democratization.

Labour conditions during the era of economic growth were brutal: working conditions were poor due to a dearth of labour rights and safety requirements. Workers worked ten hours a day and worked every day of the month. However, organized labour was forbidden by the Yushin constitution of General Park, and the government suppressed labour in order to continually suppress wages and keep labour rights to a minimum. The South Korean government’s repression of labour was further aided through political repression of its citizens: free elections were eliminated, and the Yushin constitution restricted the freedom of speech, freedom of mobility, and the right of association of all Koreans. Labour activists and political parties seeking to advance labour rights were detained, tortured, and suppressed by government authorities, creating an environment in which the government could not and would not be held accountable by its citizens through democratic means.

The government was aided in its suppression of labour through two sources of external influences: the fear of North Korea, and South Korea’s alignment with the United States. North Korea served as a perpetual source of fear for the South Korean populace, and the government utilized this fear to suppress organized labour. Organized labour was depicted as belonging to communism, and the government crackdown on labour movements was justified as defending the South Korean state from communist infiltration. This occurred in the infamous Gwangju massacre, when hundreds of protestors calling for labour and democratic reforms on May 18th, 1980 were killed, tortured, and raped by the “soft”-authoritarian regime of General Chun Doo-Hwan, a successor to General Park. In addition, South Korea’s alignment to the United States aided the various soft-authoritarian regimes to maintain power: the United States provided substantial amounts of financial assistance to prop up the capitalist regime in South Korea vis-à-vis North Korea.

However, the soft-authoritarian regime of General Chun Doo-Hwan was not to last, as millions of South Koreans embarked on a massive democratic march in 1987, and General Chun conceded to their demands leading to South Korea’s democratization in 1988. The new democratic government ceased the repression of labour movements, and labour began to organize informal unions across the country. The cause of labour movements was taken up by progressive South Korean Presidents, and South Korea, since democratization has undergone drastic improvements in labour rights and wages.

The lessons of South Korea’s developmental state should not be forgotten, as it reveals that economic development, even the most successful, have a cost, and that it is imperative to ensure that development occurs in a manner which guarantees the security and freedom of all citizens. The case study further demonstrates that a pure adherence to economic indicators provides an incomplete picture of development, and that successful development must also focus on the human dimensions of development, rather than economics alone.

Edited by Luca Brown