The Power of Public Transportation in Social Justice

Although the American civil rights struggle is largely remembered for outlawing racial discrimination in the realms of housing and voting rights, much of the movement actually centred around access to public transportation. The Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision that condemned Black individuals to “separate but equal” treatment sprang from Homer Plessy’s ejection from a “whites only” train car. Rosa Parks’ refusal to give her seat to a white passenger sparked the Montgomery bus boycotts that were key to ending segregated seating on public transit. In a posthumously published essay, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. described public transit as a “genuine civil rights issue,” linking access to public transit to access to jobs for Black and low-income individuals.

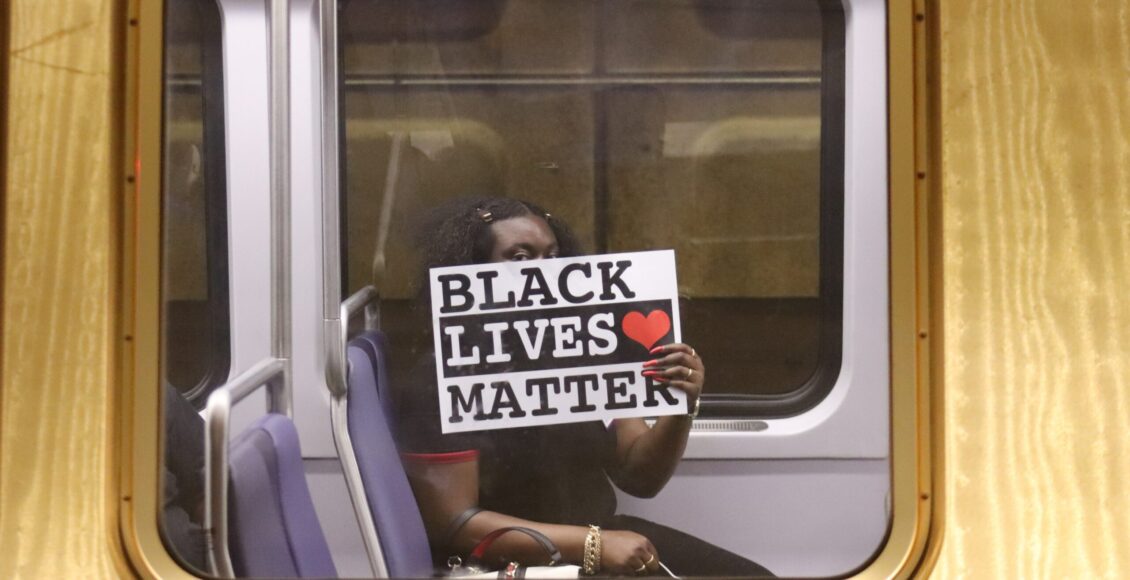

King’s words still ring true today — with renewed national debates over systemic racism since the murder of George Floyd, transportation policies continue to be central to the issue of inequality in the United States. Public transit remains essential for many Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) to access education and employment, which are essential tools for escaping the generational poverty engendered by the racist structures that define the US. Transportation policies are central to ongoing struggles for racial justice, as public transit gives racialized communities access to the economic opportunities necessary for upward mobility.

A history of progress as marginalization

Despite the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawing racial housing discrimination, the neighbourhoods of US cities remain divided by race and income. Transportation infrastructure has not only contributed to this phenomenon, but public transit systems themselves reflect the highly segregated nature of most American cities. Across US cities, low-income and racialized neighbourhoods are also those with the highest density of public transit infrastructure, while richer neighbourhoods, especially suburbs, are rarely serviced by public transit.

Although the majority of Americans commute to work by car, 21 per cent of urban residents use public transit on a regular basis. However, commuters vary substantially by race and income. In US cities, 34 per cent of Black people and 27 per cent of Hispanic people rely on public transit as their main method of transportation, compared to only 15 per cent of white urban residents. At the same time, richer and whiter communities rely on public transit at much lower rates, as they tend to be able to afford cars and live in suburbs that are well-connected to urban centres through freeways.

Past transportation spending decisions in US cities have deeply impacted communities over the last 50 years. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the federally-funded interstate highway system was built across the US. However, freeway construction was highly disruptive for urban neighbourhoods, and disproportionately bisected working-class and Black communities, such as the neighbourhood of Parramore in Orlando. The construction of Interstate 4 (I-4) through Parramore resulted in the destruction of over 500 properties inhabited primarily by Black, working-class communities. The displacement of these communities exacerbated the class and racial divide between Parramore and downtown Orlando, as in the two decades after I-4 was constructed, income inequality between Parramore residents and the rest of Orlando had increased from $500 USD to $8,000 USD. Although the few high-income individuals experiencing displacement could move to newly-constructed suburbs, BIPOC living in low-income neighbourhoods across the country were forced into public housing projects in urban centres. While routes opened from the suburbs to city centres, these same highways often lacked entrances in working-class or Black communities. Freeway development facilitated “white flight” to the suburbs, shifting economic prosperity from inner cities to suburbs, while systemically and even physically blocking displaced BIPOC communities from that same prosperity. The prevalence of freeways across the US has reduced the importance of public transportation for high-income and white residents, leaving behind underfunded public transit systems primarily used by low-income and BIPOC communities.

How can public transportation increase inequality?

For the many low-income and racialized communities reliant on public transportation, the layout of transit systems determines the accessibility of employment, schooling, and quality healthcare. Financial security, job satisfaction, and overall happiness is dependent on one’s class in the United States, and public transit is one of the many systems in America that fail to adequately support low-income individuals.

Although public transit across the US has been chronically underfunded since the 1950s, this trend has been exacerbated in recent decades. In the wake of the 2008 recession, more than 70 per cent of US transit agencies cut services, disproportionately impacting low-income and racialized communities. For example, AC Transit in Alameda County, California, which carries a ridership that is over 75 per cent BIPOC, reduced service by 15 per cent between 2009 and 2011. In a survey of AC Transit bus riders, nearly one-quarter of respondents stated that service cuts were a contributing factor to them working fewer hours or not at all, due to longer commute times.

The COVID-19 pandemic is set to worsen public transit funding cuts. Reduced ridership due to work-from-home orders has already resulted in mass revenue losses for transit agencies across the nation. In San Francisco, for example, a nearly $200 million budget shortfall will translate to nearly two-thirds of the city’s bus routes being suspended for at least 2 years, if not permanently. In the short-term, these service cuts will result in overcrowding on trains and buses, which disproportionately disadvantages BIPOC and low-income individuals that are not only more dependent on public transit, but also tend to work wage jobs that cannot be conducted remotely. Public transit service cuts have undoubtedly contributed to the higher rates of COVID-19 in low-income and racialized neighbourhoods. In the long-term, however, COVID-related public transportation cuts will also amplify the issue of inequality for racialized and low-income individuals, leaving entire communities with difficult access to jobs, goods, and services.

…But how can it reduce inequality too?

Although transportation policy has contributed to class and race inequalities across American cities, transportation is also part of the solution. In light of ongoing protests against systemic racism, investment proposals for transportation infrastructure are being framed as racial justice issues. At the national-level, the Invest in America Act was passed by the House of Representatives as part of a 2021 spending bill. The Act increases transit funding by US$105 billion over five years, and gives local communities authority over transportation funding, providing greater leeway to support transit expansion in low-income neighbourhoods. At the local level, the 2020 elections were also a referendum on public transit funding across the US. In cities such as Austin and Portland, Oregon, tax proposals to fund transit projects appeared on local ballots. Voters in Austin approved a ballot measure to raise property taxes to fund two new rail lines that will alleviate congestion on the city’s sole commuter rail line, which is overwhelmingly used by working-class individuals.

With the ongoing discussions and debates over racial inequality in the United States, the rhetoric and platitudes of political leaders must turn into tangible change. Seemingly mundane transportation policies are far from a peripheral issue in the national reckoning with race — rather, they represent the next frontier for racial justice, as transportation provides racialized communities with some of the opportunities that are necessary for upward mobility in the United States.

Featured image: “IMG_8672a” by Elvert Barnes is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Edited by Selene Coiffard-D’Amico