The Reluctant Welcome of the Calais Migrants and What It Means for France

Migrants at Calais.

Source: http://bit.ly/2f7QYwJ

Migrants at Calais.

Source: http://bit.ly/2f7QYwJ

When it comes to the dispatching of the Calais migrants throughout France, there seems to be two types of reactions. On the one hand, a supportive welcome, as in Cancale (Ille-et-Vilaine), Loudun (Vienne) or Pouilly-en-Auxois (Côte-d’Or) with pro-refugee associations helping the migrants to settle in, while on the other hand, there has been a display of deep reluctance. “Here they come…the State imposes them on us” appears on the posters sponsored by the Front National-affiliated mayor Paul Bénard in the town of Béziers (Hérault). Clearly, the arrival of the migrants has stirred up mixed feelings.

Under pressure

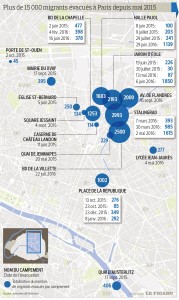

Many of the French regions designated by the government as temporary shelters have been protesting against the arrival of migrants. In Paris, the residents of the Boulevard de la Villette circulated a petition asking for the removal of migrants who had taken refuge under the Stalingrad elevated metro station in growing numbers (there were 2500 in July, 2100 in September and 3800 in November, 2016) after the dismantling of the “Jungle” in Calais. This particular location has been evacuated many times before this week, only to be repopulated later. In Saint-Denis-de-Cabanne (Loire), Louveciennes (Yvelines), Saint-Honoré-les-Bains (Nièvre), Arès (Gironde) or in Saint-Brévin (Loire-Atlantique), demonstrations not only created divisions between pro-migrants and anti-migrants, but also between mayors and the French government. In Allex (Drôme) for example, the mayor proposed a referendum asking the population whether or not they were in favour of the arrival of migrants within their area. As in Béziers, the referendum was deemed illegal by the prefecture, because “emergency accommodation is not the prerogative of the municipality, but of the State.” In Saint-Bauzille-de-Putois (Hérault), the mayor threatened to resign as a sign of protest against what he considers to be “a diktat of the State”. Reluctance occasionally turned into clear hostility, as evidenced by the acts of arson directed at welcome centers at Louveciennes, Forges-les-Bains (Essone), Billiers (Morbihan) and Loubeyrat (Puy-de-Dôme).

Source: Le Figaro http://bit.ly/2f6WpOm

Who’s to blame?

Although the hostility towards migrants appears unsettling when seen from afar, the proliferation of these quarrels and crimes should not simply be condemned as hatred or fascism, but rather taken for what they are: the frustrated expression of a significant portion of the French population. As reprehensible as they are, these cases of arson showcase the determined resistance of many. In this regard, does this resistance stem from a racial hatred of the uninvited Other, or is it due to the outrage caused by a unilateral action by the French government?

For a start, none of the councilors were consulted before the relocation: “The list [of the hosting towns] shall be channeled without soliciting the consent of the local councilors beforehand.” What is more, a range of accommodation from social housing to vacation centers and castles have been requisitioned in order to accommodate the 10,000 migrants coming from Calais, despite the legal rights of others entitled to these accommodations. The jurist Xavier Saincol thus writes: “Because of this policy that forces a regional distribution of illegal migrants, the political power de facto buries the principles of both migration flow management and the fight against illegal immigration. (…) Eventually, this display of state helplessness stimulates xenophobia.” What we see here is perhaps a manifestation of disdain and anger towards the migrants, but first and foremost an act of civil disobedience aimed at the State.

Photo taken by a friend working nearby.

What comes next

These demonstrations of unwillingness did, however, produce an effect. In Arès for instance, the municipal council voted against the accepting of 50 male migrants and also experienced two arson attempts on the local welcome center. Following on these events, the government decided to send only 8 persons. In Saint-Bauzille-de-Putois, where the mayor had threatened to resign in order to refuse the arrival of 87 migrants, 43 were sent instead.

An equally important question would be whether the country is able to sustain the Calais migrants and the ones yet to come or not. So far in 2016, the cost of aid to asylum-seekers has reached 315 million euros (while the overall budget allocated to the refugee crisis has surpassed one billion euros), and although the government plans for “only” 220 million euros in 2017, chances are this budget will not be respected, according to the LR deputy Eric Ciotti who speaks of “budgetary insincerity”. The French general accounting office (Cour des Comptes) also made a worrying statement: “75 % of the asylum applications are rejected every year on average. Despite their obligation to leave French soil, only 1% of the expelled [illegal migrants] have indeed been kept outside of French borders.” Since January 1st, 2016, only 1.384 have indeed been expelled. In other words, the majority of the migrants that have not been granted the status of refugee – let us not forget the semantic distinction between a political refugee and a migrant moving for economic reasons – have not left the country.

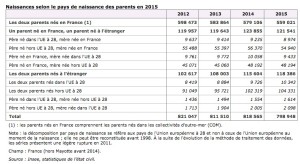

Source: INSEE http://bit.ly/2f6Zy09

On this matter, the influential geographer Christophe Guilluy describes the fragility of France in an interview with Le Figaro: “Beside the social question, the matter of identity is a reality. France has become a multicultural society, even though the choice has never been explicitly assumed by our governments. And, in a multicultural society, assimilation does not work anymore. (…) Why does the worker of Hénin-Beaumont vote for Marine Le Pen [the leader of the extreme right party] rather than Jean-Luc Mélenchon [the leader of the extreme left] who promises him a minimum monthly wage of 1500 EUR?” France is indeed changing, as the study of the Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE) would suggest: in 2015, a 7.8% decrease in births from parents born in France, compared to an increase of 6.07% in births from parents born outside of France.

Be it with a rush of welcoming acceptance or reactionary hostility, the formation of “mini-jungles” is what everyone is striving to avoid. As the volunteer initiative in Cancale suggests, there is hope for a successful integration of the Calais migrants, the lingering case of Paris, however, might be a sign that the “jungles” cannot ever be fully dismantled. More than that, it becomes clearer every day that France lives on borrowed credit and cannot financially sustain these new arrivals without risking further dividing its own population.