The Senate Rules are Broken: Why don’t Democrats want to fix them?

The minutiae of Senate procedure is rarely a key platform for presidential candidates. Generally, those running for office talk big ideas and their visions for the future in sweeping terms. 2020 is no exception. Democrats have recently shifted to the left on several issues, and candidates have advocated for progressive change, like free health-care, tuition-free college, and a federal job guarantee.

However, it is one thing to talk vision, and another to get into the gritty details of how exactly candidates plan on getting things done. The reality of the matter is that the current state of Senate rules makes it almost impossible for any of these big ideas to come to fruition.

The Senate filibuster represents a tremendous obstacle for Democrats trying to pass ambitious legislation; Democratic presidential candidates ought to seriously consider getting rid of it entirely.

So, what exactly is the filibuster? It was originally created in 1806, as a measure to ensure that minority voices were heard before the Senate voted on an issue. At the outset, a filibuster could not be interrupted by the Senate as long as the filibustering Senators continued talking. A vote could not be had until these Senators felt that they had been adequately heard. In 1917, the Senate adopted a procedure called a “cloture vote”; this meant that a super-majority of 60 could decide to end debate on the issue and force it to go to a vote. The longest filibuster in history was held by South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond in 1957, when he spoke for 24hrs and 18 minutes to block a vote on Civil Rights Legislation.

In 1975 the Senate made it easier to filibuster, by no longer requiring filibustering Senators to actually stand on the floor and make their case. On top of this, rules were implemented that allowed other business to be conducted while a filibuster was underway, also making it easier for Senators to prevent bills from going to a vote. This was done in order to avoid the government from shutting down over disagreements on one bill, but effectively made fillibusters more viable and commonplace.

Since 1917, the filibuster has been used 1,300 times. 600 of these occurred in the last 12 years.

In the US, each state has two Senators, regardless of population size. It takes 60 senators to vote to override a filibuster. Therefore, the 42 senators representing the 21 least populous states, and a combined 11% of the population, have the power through the filibuster to stop bills proposed by the remaining 89% of the population. A small number of senators can effortlessly place their own political agenda above the work of government, without breaking any rules and with little consequence.

In theory, this rule was created to encourage comprehensive debate, and ensure that everyone’s voice was heard. In practice, however, senators representing as little as 11% of the population are filibustering even motions to proceed, blocking the possibility of debating bills at all.

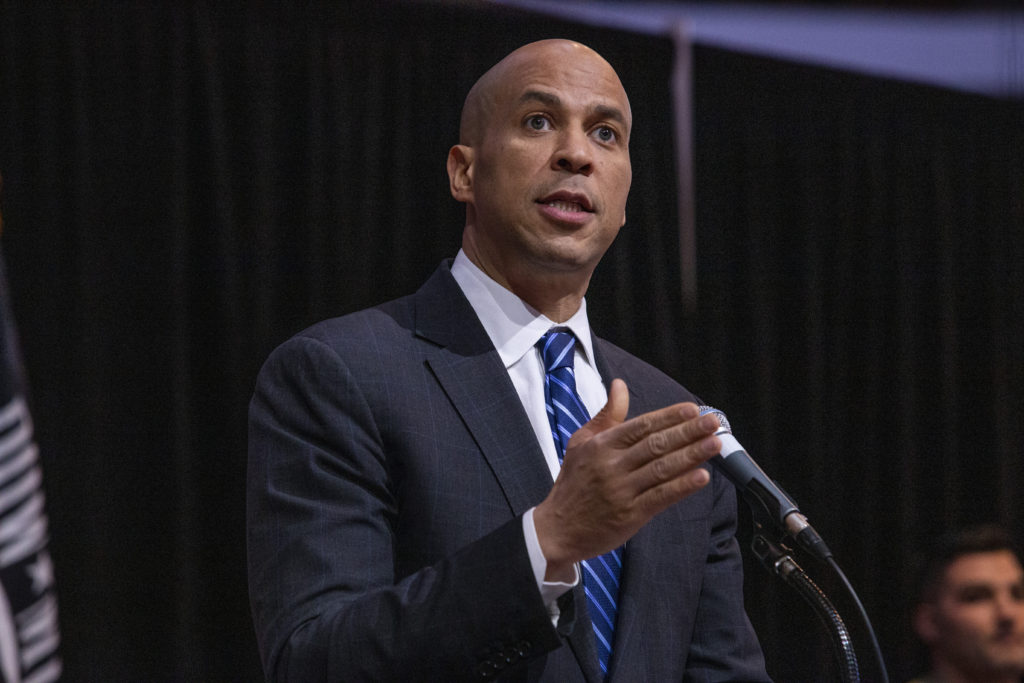

However, most Democrats running in 2020 are opposed to changing the rules. Bernie Sanders has expressed that he is “not so crazy about getting rid of the filibuster.” Cory Booker has also defended it, and Kamala Harris is “conflicted” on the issue. Yet, all of these candidates have bold, progressive, plans that are unlikely to get the 60 votes required to beat the filibuster.

One argument for retaining this measure is that it promotes bipartisanship. Theoretically, the filibuster helps maintain stability and avoid extreme policy shifts from one election to the next. Democratic presidential candidate Kirsten Gillibrand stood by it, stating: “If you do not have 60 votes, it just means that you haven’t done enough advocacy and you need to work harder.”

Considering that there are currently 47 Democrats in the Senate, her reasoning entails either Democrats winning 13 more Senate seats, or convincing up to 13 Republicans to side with them on issues like “The Green New Deal” and free healthcare. Both scenarios are unlikely.

The problem with this premise, is that it does not reflect the state of the modern politically polarized Senate. When the political climate is centrist, with parties disagreeing on methods to be employed rather than overall vision, bipartisan compromise is more likely. As both parties have moved to their respective poles in recent years, Republicans and Democrats have less and less in common policy-wise. In 2019, when the filibuster is employed, it is done so to actively forge gridlock, rather than to create opportunities for further discussion and compromise.

The primary justification for keeping the rule intact, however, is that although the filibuster may be frustrating when in the majority, Senators are thankful for its existence when the tables turn. Among current Senators, 68 have experience in both the majority and the minority and are therefore able to look at the issue from both sides. If Democrats do win across the board in 2020, and decide to scrap the filibuster in order to pass major legislation, they risk repeal as soon as Republicans take back power.

Yet, the arguments for killing the filibuster certainly outweigh reasons for keeping it.

Democratic governments around the world function just fine without having loopholes in place to protect the opposition. Other democracies pass laws by a parliamentary majority. These laws can be undone by a different majority later, but then this is merely reflective of what the electorate has voted for. If the laws passed are well-liked, then the incumbent government does not have to worry about their repeal.

Correspondingly, if Democrats were to pass popular laws that actually make a tangible difference in peoples lives, it becomes harder for the opposition to justifiably reverse them. Without the filibuster, Democrats could get so much done with just a simple majority, like campaign finance reform, a new voting rights act, and statehood for the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. All of these reforms would help increase Democrats’ representation in government, and ensure that changes implemented are not immediately reversed.

The filibuster is not a part of the constitution, it is just a Senate rule. Getting rid of it is a fully legitimate action, especially since steps have been taken to dismantle it in the past. Republicans have already discarded the rule for Supreme Court nominations; doing the same for health-care reform would not be unprecedented.

Finally, it is important to remember that a Democrat victory in 2020 is likely to result in a Republican backlash in the 2022 midterms. This gives Democrats feasibly two years to materialize their ambitious plans, and they ought to make the most of it. Therefore, filibuster reform should be a top priority.