The Skripal Case: When Claiming the Moral High Ground Becomes Evidence

On April 3rd, Gary Aitkenhead, Porton Down’s Chief Executive, declared that the chemical research facility had been unable to verify whether the nerve agent used on Yulia and Sergei Skripal in Salisbury on March 4th had originated from Russia. This bluntly contradicted a statement made by Boris Johnson a couple weeks before, who claimed in an interview with DW News that this conclusion presented “no doubt.”

This has not been the only element casting doubt on the seemingly straightforward explanation Britain has been quick to assert from March 12th. Theresa May then affirmed that Russia was “highly likely” to have carried out the attack and that the ‘Novichok’ nerve agent either directly originated from Russia, or was “allowed […] to get into the hands of others.” Various experts have since suggested that other states may have developed the nerve agent by drawing on several possible sources.

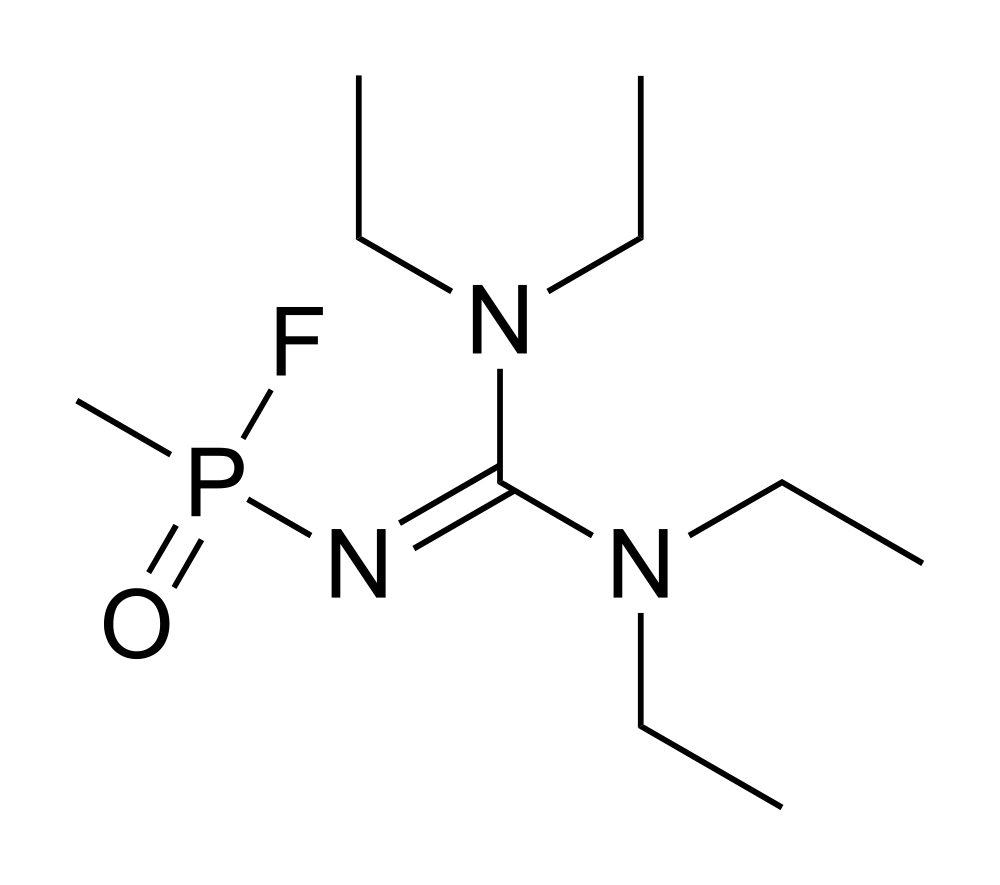

For one, it is likely that Western powers gained access to several Soviet state military secrets – either thanks to Soviet-era intelligence work or during the chaotic 1990s. The US may notably have collected physical evidence on Novichoks during the 1999 clean-up of the Nukus chemical weapons testing facility. Several countries may have also pursued their own research – at least for defense purposes. Most significantly, Vil Mirzayanov, a former Soviet state chemist who revealed the existence of Novichoks in 1991, shared alleged Novichok formulas in a book published in 2008.

These testimonies suggest that the UK’s assertion on the origin of the nerve agent is either groundless, or at the very least omissive – there is ostensibly more than two possible explanations. In the meantime, the OPCW investigation has confirmed Porton Down’s findings about the agent’s identity, but has not brought any new element indicating where it may have been manufactured.

The fact of the matter is that, from the beginning of the affair, Britain has refused to offer a dialogue based on evidence. Instead, the UK’s public discourse has heavily relied on framing the dispute as a moral battle between the West’s alleged righteousness and Russia’s attributed role as a rogue state. Britain built its position around this dichotomy between good and evil, ultimately using it as evidence in and of itself.

Russia’s involvement in other international disputes has repeatedly been brought up in conjunction with the case. Boris Johnson has presented Vladimir Putin’s alleged lust for revenge – an argument repeated in the media – as well as Russia’s “smug” behavior, as proofs of guilt. UK officials’ own behavior has at times been outright contemptuous. Every Russian attempt at multilateral outreach has been systematically dismissed as “ludicrous,” “perverse,” or a “diversionary tactic.”

Such arguments, without a direct link to the case but rather based on, and displaying, an assumption of Russian malice, have been largely echoed in Western media. Yet the role of evidence should be to imply guilt – not to be built over it.

To entitle oneself to the moral high ground comes with the heightened responsibility to uphold the principles it ought to represent – transparency, free speech, enlightened debate and, most importantly, due process. Principles that have all been tarnished in the present case. In the wake of Aitkenhead’s interview, even traditional allies such as Germany prompted the UK to release more evidence to back up its position, for the sake of transparency.

And Britain should certainly uphold higher transparency standards. Several commentators indeed pointed out that the 2003 invasion of Iraq, among others, was a destructive consequence of such flawed intelligence. It also constituted a severe blow to the legitimacy of Western global leadership. Yet the treatment reserved for those who have come out early against Britain rushing to conclusions may be the most harmful outcome of the path chosen by the UK to tackle this affair on the international stage.

We have witnessed that to merely share a similar opinion with the Russian state or media, however sound it may be, is now dismissed as support for the Kremlin’s propaganda machine. Framing the debate in absolutes only fosters polarization, hijacks any attempt at reasonable discourse, and eventually contributes to significantly reduce the zone of compromise by sewing animosity and discord.

If the West truly ought to build a constructive discourse with Russia and efficiently fight misinformation and polarization, it must not play with the very same cards it constantly accuses Russia of using. Britain cannot have it both ways. It must realize that such actions, far from only contributing to bringing Russian-Western relations to its – yet again – lowest point in decades, are also undermining the very foundations liberal democratic values are built on.

Edited by Sarie Khalid