The Stock Market Correction One Month Later: What it Means and What it Doesn’t for the Average Citizen

For those familiar with market-related news and analysis, there is no doubt that investors have had a lot to celebrate this past year. Cheering on a global market that has been unusually bullish, pundits and analysists have marveled at the strangely calm upward trend that seemingly wouldn’t waver. Since Donald Trump’s election, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has soared more than 40% while the technology-heavy S&P 500 gained an impressive 20% on the year. Meanwhile, markets indices in Asia, such as the Nikkei and Hang Seng, have jumped thousands of points in the past year. Then, in the beginning of February, came a swift “correction” of sorts – an average fall of more than 10% in global markets – that went away almost as quickly as it came, leaving investors on the edge of their seats and increasingly certain that this strange prolonged period of calamity has finally come to an end. While nerves remain tense on Wall Street, what can be said about the common folk; those on Main Street? In a news cycle recently populated by news equating economic health to the rising stock market, it is important to take the time to examine why conflating this data can misrepresent and even falsify the financial situation of lower and middle-class citizens, while concurrently exaggerating policy measures beneficial to markets but detrimental to the average citizen.

What Happened?

While financial analysts are at odds as to exactly what triggered the selloff, a couple of underlying sentiments provide a valid jumping-off point. First, job growth was much higher than anticipated in January, as both average hourly earnings and payroll additions toppled economists’ expectations and climbed at the fastest pace since prior to the so-called Great Recession of 2008. In turn, many investors quickly caught on to the meaning of this data: inflation, or, a fall in the purchasing value of money. While inflation is a natural phenomenon that signals healthy economic progress and expansion, too much of it can make products and expenses untenable, especially when wages are not keeping pace. Thus, rising fears of inflation are more often than not an indication that the US central bank, the Fed, will increase interest rates to correct for monetary devaluation; another factor experts have pinpointed for February’s market correction.

Does the Market Work for Wall Street or Main Street?

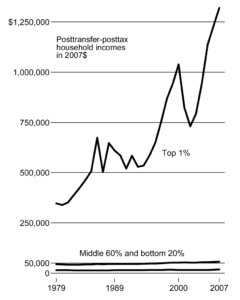

Given Wall Street’s recent tumble in share prices, what should the everyday layman make of it, if anything? Generally speaking, a rise in the average wage for workers should be met with enthusiasm rather than scorn by investors and workers alike. Americans have suffered from rising income inequality long before 2008’s Great Recession gripped world markets, and coupled with the indelible trend of wage stagnation, it seems paradoxical that rising wages would have such an adverse effect on the markets. An argument can be made attesting to the nuances of “overly valued” stocks, but pointing this out, there does seem to be a disconnect or even an adversarial relationship between market movements and the economic well-being of the average worker. Take, for instance, the concept of inflation mentioned earlier: When a wage report characterizes earnings as higher than anticipated, benefitting workers, investors panic, selling off assets in the biggest dump since 2008. It may very well be argued that an increase in wages eventually leads to a corresponding increase in the price of goods, but when real wages were only 10% higher in 2017 than they were in 1973, such a negative reaction tacitly demonstrates the existence of an inverse relationship.

Even if a price-effect were to gain traction and begin to increase costs above the rate of wage growth, the Fed’s response–that is, the raising of interest rates–acts as a countermeasure against out-of-control price increases. A side effect of the Fed’s action has again been partially attributed to this selloff, and again it showcases the adversarial relationship between markets and laymen for a few reasons. First, interest rates have been abnormally low in the past few years due to the Fed’s response to the 2008 financial crisis. But with the economy improving, it’s only natural for the Fed to raise interest rates to prevent the economy from overheating. Businesses, however, need to accept that the American economy is on a healthy pace to recovery and give a nod to interest rate hikes, not reject them via a massive selloff in stock. In addition, a higher interest rate actually benefits some consumers: Typically, raising the interest rate increases the value of the country’s currency in relation to others’, meaning more money in the wallets of Americans living abroad or planning a vacation.

One point to take away from this information, however, is that what’s good for the market may not translate to benefits for the average citizen and, in fact, may be adversarial toward them. If stock markets are to be considered an indicator of economic health, then they ought to be considered only a segment of it. A more honest approach would measure the economy from the perspective of Main Street and work to correct stagnant wages and a shrinking middle class. Still, we shouldn’t be so quick to entirely dismiss the role the stock market plays for the 75 million “Baby Boomers” who are increasingly relying upon market trends for their retirement accounts, like Canada’s Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) or an American 401K account. A large drop or correction in the stock market could derail retirement plans for those on the brink of retirement, and likewise, a bullish market can shave off the time needed to reach the adequate amount of savings needed for a comfortable retirement. In addition, other financial instruments tied to the value of the markets could be similarly detrimental or beneficial to those looking to retire.

By framing the impacts of the recent correction in the stock market as a measurement of who the market works for, we have established that workers may find both upward movements as well as subsequent monetary policy adjustments detrimental to their financial situations. To solve this problem is to solve a bigger picture, being the growing disconnect between the interests of companies and corporations and those they employ. Because of stagnating pay and a growing income gap, monetary policy must shift in favour of the working class by promoting higher wages and raising the interest rate.

Edited by Phoebe Warren