The Tale is Wild: the crisis of the Argentine government, the death of Nisman, and the 2015 elections

The day I arrived in Buenos Aires to start my study abroad, the 18th of January, the Argentinian federal prosecutor, Alberto Nisman, was found dead in his apartment. Being a political science student, I was already awaiting a very interesting semester here in Argentina, watching the development of the elections year, which according to what I had been told, is always very fascinating and impassioned. But with the death of Nisman, I realized that I was going to be witness to a historic election, an election which was possible going to revolutionize the Argentinian political scene. This is because Nisman wasn’t just any old lawyer: Nisman was going to take the federal government of President Christina Fernández de Kirchner (CFK) and her Minister of Foreign Relations, Hector Timerman, to court for having negotiated secret pacts with the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The day I arrived in Buenos Aires to start my study abroad, the 18th of January, the Argentinian federal prosecutor, Alberto Nisman, was found dead in his apartment. Being a political science student, I was already awaiting a very interesting semester here in Argentina, watching the development of the elections year, which according to what I had been told, is always very fascinating and impassioned. But with the death of Nisman, I realized that I was going to be witness to a historic election, an election which was possible going to revolutionize the Argentinian political scene. This is because Nisman wasn’t just any old lawyer: Nisman was going to take the federal government of President Christina Fernández de Kirchner (CFK) and her Minister of Foreign Relations, Hector Timerman, to court for having negotiated secret pacts with the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Let’s rewind a bit. This whole story began more than twenty years ago, with two terrorist attacks in the capital, Buenos Aires. On March 17th 1992, a car bomb detonated outside of the Israeli embassy, killing twenty-nine people and wounding more than 250 others. Two years later, on June 18th 1994, a bomb exploded in the Mutual Israel Argentina Association (AMIA) building, leaving eighty-nine dead and more than 300 wounded. It remains the deadliest terrorist attack in Argentine history. Investigations into the two attacks were assigned to two judges in the Argentine Supreme Court, but although the terrorist group, Islamic Jihad, claimed responsibility for the embassy attack, nobody was convicted in either attack. In 2005, one of the judges, Jose Galeano, in charge of the AMIA investigation, was impeached for bribing a witness in the case and burning evidence; today, he is awaiting criminal trial for hiding evidence.

Enter Nisman. He was named by ex-president (and husband of CFK), the late Nestor Kirchner, in 2004 to investigate the AMIA attack. In 2006, Nisman accused a few Iranian officials of involvement with the attack, accusing them of having helped Hezbollah militants carry it out. A grave accusation, which resulted in an ongoing Interpol investigation. However, at the start of 2015, Nisman made an even more shocking accusation: he accused CFK’s government of having negotiated with the Iranian government, denouncing “an alliance of the Executive with terrorism”. Nisman (building on accusations previously levered by the journalist Pepe Eliaschev) said that in 2011, CFK and the Iranian government had reached an agreement, exchanging gas (of which Argentina has a deficit) for impunity for the Iranian officials accused of the AMIA attack. Nisman was to present a formal accusation in front of an Argentine congressional committee only a few hours after his body was discovered. As of today, his denunciation was refused by federal judge Daniel Rafecas, but another prosecutor, Gerardo Pollicita, who appears to have taken up Nisman’s mission, is appealing against this decision.

The mystery surrounding Nisman’s death has shaken Argentine society. There are many theories about his death which accuse all political parties and actors in the country. Amongst the accusations circling, there are obviously those against CFK, but her response to these allegations was to blame some “rogue agents” from the Argentine Intelligence Services (SI). Following her official theory of the murder, CFK dissolved SI and declassified its documents about the AMIA attack.

In true Argentine fashion, there was a march in Buenos Aires on February 18th to pay homage to the prosecutor and protest the government’s reaction. However, contrary to many Argentine protests, the silent march for Nisman was apolitical: the organizers asked that there weren’t any political campaigns and the demonstration did not endorse any ideology or political party. The march in Buenos Aires brought together hundreds of thousands of persons and there were similar marches in other Argentine cities and around the world.

I am not Sherlock Holmes. My job isn’t to investigate the truth behind this scandal. What interests me is how his death could affect the elections and the future of Argentine politics. It is a question which preoccupies many: The New York Times published an article asking the effect of Nisman’s death on the elections and Sergio Berensztein, a well known Argentine political scientist who publishes reports on Argentine politics, included Nisman’s death and the ensuing march in his measures of political opinion published March 11, 2015. I had the opportunity to speak with Carlos Sanguinetti, an Argentine with a degree in economics, and a specialist in civic issues, to ask him about his opinion of Nisman and the effect he could have on October’s elections.

[Interview translated by author from Spanish.]

MIR: Do you have a theory on what happened with Nisman’s death?

CS: I have the impression, based on my readings of the previous events, that the denunciation which Nisman presented held solid foundations. In reality, this denunciation of Nisman’s wasn’t new, since the journalist Pepe Eliaschev had already made it in March 2011 to Nisman and in the press. This denunciation made public in an institutional setting like a congressional committee would have caused a political crisis of importance and this didn’t suit the governing party nor the Iranians involved in the agreement. Even so, I don’t have any idea who killed Nisman.

MIR: What do you think of how the government acted/reacted to Nisman’s death?

CS: The facts speak for themselves. In the days before he died the President and her close advisers pestered him verbally, they didn’t give him the security which corresponded to him, didn’t publish his denunciation on the Public Ministry’s website etc., etc. After his death, they hurried to say he had committed suicide, they never expressed sorrow for his death, and they threatened and pressured the prosecutors who organized the march of silence on February 18th in his honor.

MIR: Did you go to the march? What is your opinion of the march, in general and compared to other marches you have seen or participated in?

CS: Yes, I went to the silent march from the Congress to the courtroom in front of Plaza de Mayo*. The amount of people who went impressed me. The torrential rain during the march gave it some epic qualities. Almost nobody wanted to leave. I saw members of the middle class, which is to say, not only people from the highest economic bracket. I saw great civil respect, such as I had never seen in the innumerable civic marches there have been in Argentina since the implosion of the financial crisis of 2001.

MIR: Do you think Nisman’s death could exercise an effect on the elections? How and why, or why not?

CS: I think yes, although history shows that Argentines are too lazy and with little civic culture and so sometimes the effects are diluted with time, and there are still months before the elections. No matter what though, I believe there are various concrete effects:

- The population has perceived that there was violence in Nisman’s death, that it was a simple suicide, and even if the intelligence services could have been involved with his death, the government has something to do with it. And in that sense, if the existing government, which in my opinion isn’t really democratic, thought to realize acts of political violence in the months previous to the elections, it will be difficult for them to do them because they would not be able to avoid being branded for having done them purposefully so as to not relinquish power.

- Nisman’s death installed definitively the collective conscience that this is a government begun by the president which is not only authoritarian but sometimes mafia-like, and the level of impunity which has come about in this decade with this government can destroy our lives from one moment to another. This has lost some of the intention to vote for a Kirchnerist candidate in the poorest sectors in the biggest cities and greater urban areas, even though my impression is that this loss of potential votes isn’t in itself decisive. But the interesting thing is that the shock which Nisman’s death generated forces some of the presidential candidates like [Mauricio] Macri and [Sergio] Massa to talk against impunity and corruption, problems which both candidates had until now not held in their agendas. My impression from analyzing Argentine history is that as long as there continues to be impunity, Argentina will continue to be an institutionally precarious country and because of that, will lose a motor of economic development.

- The march represented a psychological breakdown on the part of the population and the candidates of the opposition noticed this. Seeing that the “republic is in danger”, they are allowing more dialogue between opposition parties. I believe that Nisman’s death is what ended up convincing the parties of the moderate center-right to forge an electoral group in the preliminary elections (but not the elections of October 25th) and the parties of the center-left to decline their candidatures because of how low the surveys measure. I think that the most favoured by all that has occurred is the Propuesta Republicana (PRO) candidate Macri.

- The march was a recognition of the prosecutors and judges who judge denunciations of political, corporate, and syndical corruption during the twelve years of [CFK’s] government, which until now the government had gotten delayed and held back. Therefore I believe that for the first time there are chances that some corrupt officials will be pursued. It will be very important to see what sentence will be given in the trial for the “Tragedy of Once” whose oral trial will begin in June or July.

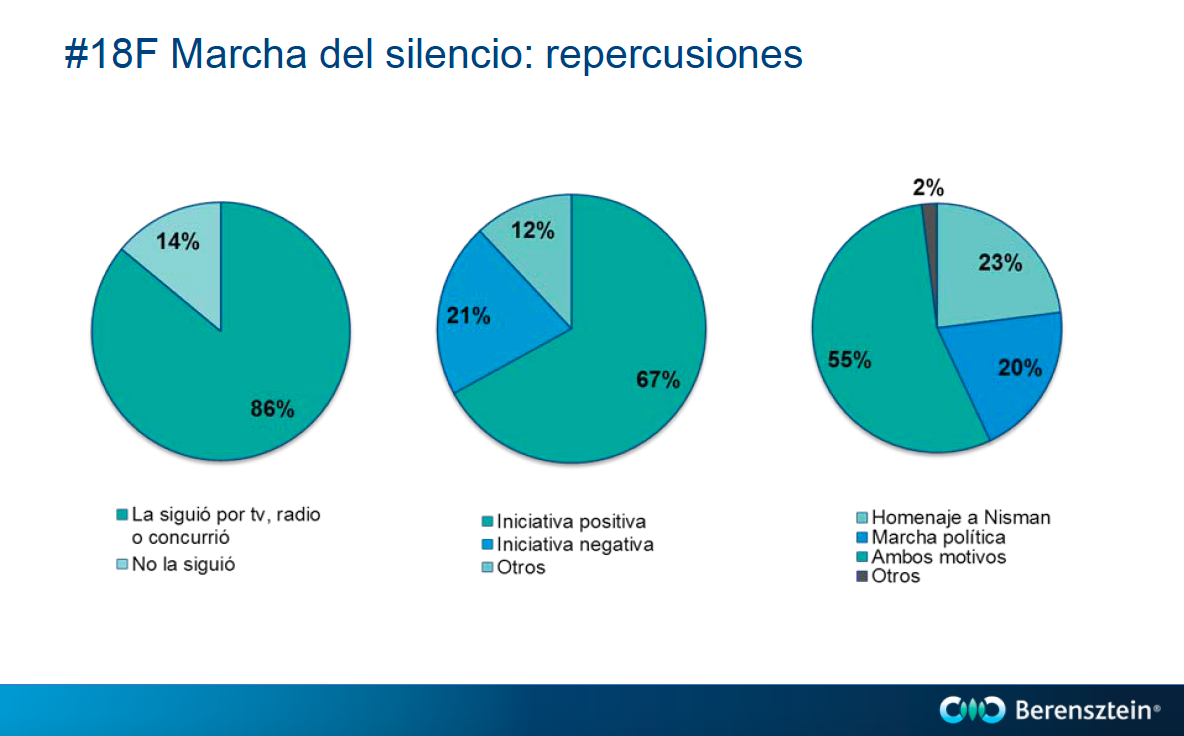

Sanguinetti’s prudent optimism appears supported by Berensztein’s surveys[1], which suggest that 52% of the population disapproves of CFK’s government and 78% want at least some changes under the next administration. The surveys show that the large majority of Argentines (86%) followed the march on February 18th, and 67% think it was a positive initiative. Finally, the surveys put opposition candidates Massa and Macri as some of the poll leaders, perhaps indicating that Argentines are tired of the Kirchnerist project, which looks bad for the Peronist candidate which CFK will endorse after the primaries. The pollster group Ipsos published a survey indicating that 44% of the population preferred to vote anti-Kirchnerist, compared to only 23% who said they planned to vote Kirchnerist[2].

Sanguinetti’s prudent optimism appears supported by Berensztein’s surveys[1], which suggest that 52% of the population disapproves of CFK’s government and 78% want at least some changes under the next administration. The surveys show that the large majority of Argentines (86%) followed the march on February 18th, and 67% think it was a positive initiative. Finally, the surveys put opposition candidates Massa and Macri as some of the poll leaders, perhaps indicating that Argentines are tired of the Kirchnerist project, which looks bad for the Peronist candidate which CFK will endorse after the primaries. The pollster group Ipsos published a survey indicating that 44% of the population preferred to vote anti-Kirchnerist, compared to only 23% who said they planned to vote Kirchnerist[2].

However, it is also important to look at Argentine history, as Sanguinetti says. Berensztein’s report also says that it is too early to tell what will happen in the elections: we are only in March, and even though Nisman’s death currently occupies the minds of Argentine voters, the awful state of the economy will probably regain the foreground. Kirchnerism, heir to the Peronist ideology so central to Argentine political discourse, promises a project of social justice which although has not functioned smoothly under CFK, continues to hold appeal for Argentina’s popular class. As is seen in the video which Wyre Davies made for the BBC on the image of CFK, she cultivates a cult of personality like the Peron couple, a sort of hyperpresidency, as it is referred to by Berensztein. This is not unique to CFK: the hyperpresidency and the cult of personality are staples in the Argentine democracy and Peronism, the party which has dominated politics. All of this will exercise an effect in the elections, and combined with the relative disorganization of the opposition, where there are many leaders competing, with fragmented parties and lacking large networks of support, could outweigh the effect of Nisman and his accusations.

I think we need to wait and watch the development over the next few months, especially with the provincial and primary elections. But I also believe that maybe, this time, Argentines will finally be sufficiently fed up not only with the sickly economy but also with the dishonesty, corruption, cults of personality, and manipulation which have characterized the CFK administration. I do not know who will win the elections in October, but I hope that he, or she, will learn from CFK’s mistakes and that they will be able to begin to resolve the problems and divisions in Argentine society.

*Square in Buenos Aires where the federal government building, la Casa Rosada, is located and which hosts most Argentine political demonstrations.

___________________________________

[1] Sergio Berensztein, “El comienzo del final Una transición larga y compleja en medio de la creciente incertidumbre electoral”, March 11, 2015.

[2] Ipsos, March 2015.