The Tragedy of Colonial Borders

Four years into the crisis, the international community continues to struggle in forming a coherent response to the situation in Iraq and Syria. The questions of who gets a seat at the negotiation table, whether to impose a no-fly zone, and how to handle the ever-growing flood of refugees are met with a disparate range of answers within foreign policy circles. Desperately few of these are meaningfully considered, much less put into action, by international leaders. But these solutions, especially those appealing to world powers, are flawed by a constant delusion: that Iraq and Syria are even salvageable.

I am not here proposing that the conflict will carry on indefinitely; under even the most pessimistic projections some form of ceasefire and stalemate will eventually take place. The delusion is that Iraq and Syria can ever again become functional, cohesive, ‘Westphalian’ nation-states. The latter has not been for over four years, while Iraq has existed in an existential limbo since the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. Nor, we must admit, were they particularly successful sovereignties prior to their implosions. Both are marred by a short and bloody history of chronic political instability, brought together only under despotic regimes that secured their power through body counts. While I’m skeptical of denying agency to anyone who engages in systematic murder, not to mention flies across the world to join a genocidal jihad, it’s important to understand that the root of this problem doesn’t lie in the hands of the people we call Syrians and Iraqis. The catalyst lies in the demarcation of Mesopotamia and the Levant between France and Britain in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which turns 100 year old this coming May.

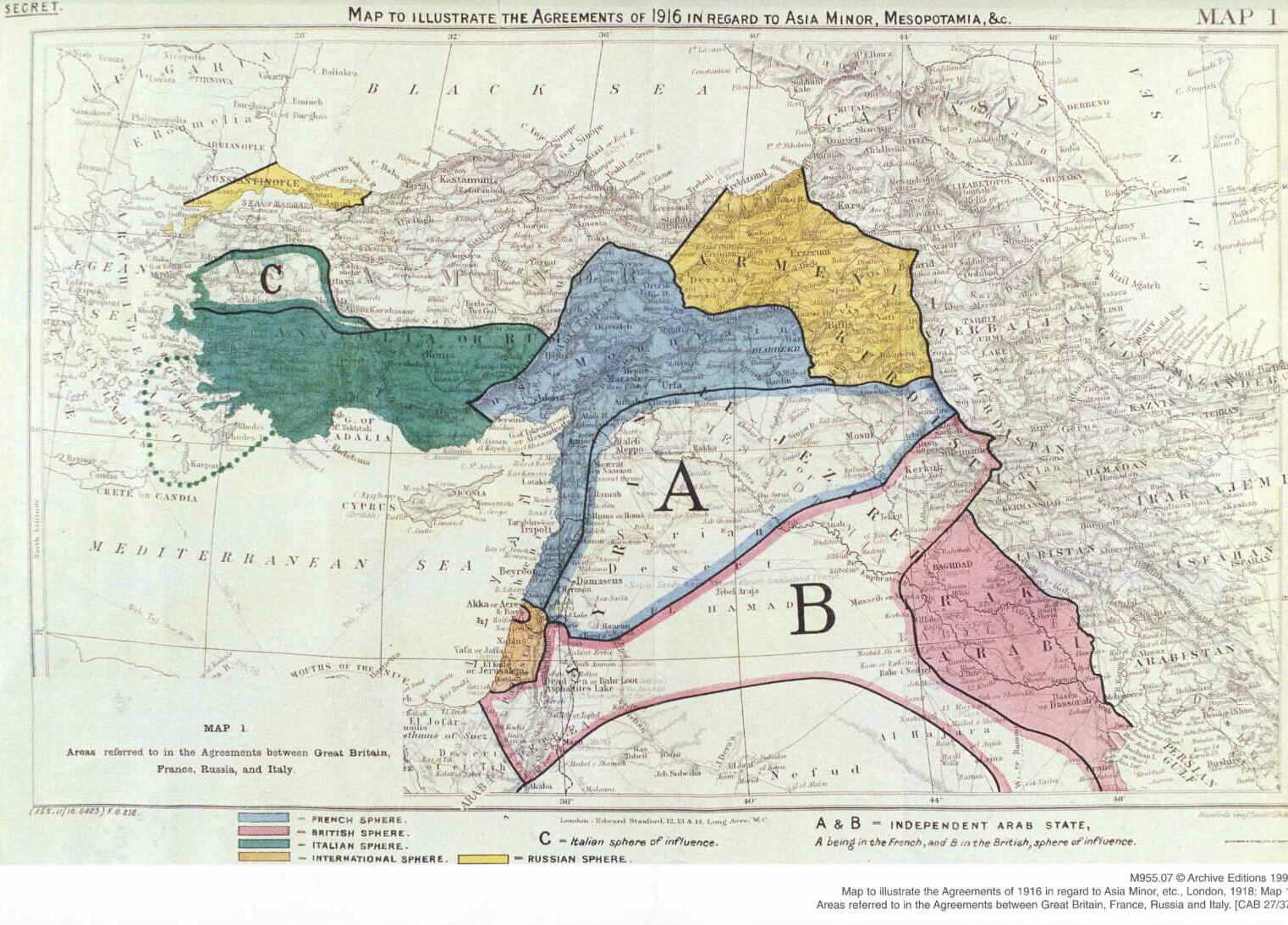

With the First World War well under way the Entente powers signed the treaty, which was to divide the imperial territories of the soon to be defeated Ottoman Empire into French and British spheres of influence and control. What must be stressed in the present context is how utterly irrelevant the geographic positioning of ethno-linguistic groups was to the colonial delegates. In James Barr’s work on the subject, A Line in the Sand, he quotes Sykes as saying, “I should like to draw a line from the e in Acre to the last k in Kirkuk” on the map they were using that evening, hardly the logic upon which to build a successful nation state (p.12). The decisions made in a few brief meetings by two aristocrats, under the sway of whiskey and cigars in a posh London social club, laid the foundations of Iraqi, Syrian (Trans)Jordanian, and Lebanese nationhood, with major implications to the development of Egypt, Israel, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states.

This approach followed the practice of colonial division in Africa: grotesque vertical and horizontal borders that paid no mind to the intricate division of tribal and ethnic territory which they cut through. Lines, which fit so neatly into European maps, translated into devastating consequences on the ground after the waves of independence in the 1950’s and 60’s. The native lands of one group taken and arbitrarily assigned to another; historically cohesive ethnic clans segregated into neighboring states only to find themselves as prosecuted minorities; disparate tribes with long histories of conflict clumped into a single nation and expected to form a common identity; it is little surprise that the history of Africa in the second half of the twentieth century is one of seemingly constant bloodletting, only catching the international community’s attention only when the violence gets particularly genocidal.

The states designed as Iraq and Syria, likewise Libya, Yemen and many more around the world, were neither large enough to force co-existence upon their many ethno-linguistic groups, as the Ottoman Empire did, nor with a common enough historical identity to form a cohesive society, as is Oman. They lacked a common, historical identity that earlier defined European states and helped Asian ones recover from their own colonial experiences. Instead, there were decades of fragile political rule punctured by frequent military coups. In both countries, centralized states only emerged under dictators, Saddam Hussein and Hafez al-Assad respectively, who held no reservations in the violence they would inflict upon their subjects to maintain power. While the complexities of managing an artificial state is worth at the very least an article in and of itself, some details are worth mentioning here.

Instead of investing in the development of their country, regimes are forced to spend what little precious capital they have in cash transfer to tribal leaders to buy their loyalty, giving them a stake, though certainly not a very reliable one, in the survival of the regime. At the very least, this usually involves hiring inordinate amounts of and civil servants to keep them employed and out of trouble, suffocating the private sector with a corrupt and inefficient state economy. Armies, the perennial source of insurrection, are designed to protect the regime and not the country. They are, with rare exceptions, lousy fighting forces – witness the complete collapse and desertion of 30,000 well-equipped Iraqi Army soldiers in the face of 1,300 ISIS fighters in the Fall of Mosul last summer. Ultimately, failing to form a cohesive national identity, regimes instead resort to the worst kinds of jingoism. George Bernard Shaw may as well have been thinking of modern Middle Eastern states when he reflects that, “A healthy nation is as unconscious of its nationality as a healthy man is unconscious of his health. But if you break a nation’s nationality it will think of nothing else but getting it set again” (Shaw 1904, p. xxxvi) Popular approaches include whipping up xenophobic violence against a troublesome religious minority or a pointless war with an irksome neighbor.

A popular mid-century argument against fractionalizing artificial states in the Middle East and Africa was that tribal sized countries would be too small and weak to defend themselves, leaving them tempting targets for their larger neighbors’ military aggressions. Aside from recent history showing us that size really doesn’t matter, it is intranational wars, civil conflicts like the Lebanese Civil War or the sectarian strife of the Rwandan Genocide rather than cross-border conflicts than have been the cause of most deaths in in the post-colonial eras. Furthermore, it is often the displacement of ethnic groups across bordering states that has dragged external actors into domestic conflicts. Uganda’s Idi Amin involved himself in the First Sudanese Civil War because he shared ethnicity with the southern rebels Kakwa ethnic group. It was under the pretense of liberating Arabs in Iranian Khuzestan that Saddam Hussein started the Iran-Iraq war. At the very least, ethnic cleavages give opportunities to foreign powers to exploit tensions, support rival factions, and sustain the conflict for longer than it would have otherwise lasted – this describes the trajectory of maybe half the Cold War’s proxy battles. I could go on for much longer but hopefully these few examples have convinced you at least reconsider the desirability of artificial states.

Why does the international community refuse to consider breaking them up? When leaders even acknowledge the possibility, it’s usually to argue that to do so would create chaos – however I struggle to see what stability there’s left to salvage in Iraq, Syria, Yemen or Libya. Their reluctance shouldn’t be surprising; notice the institutional resistance to the independence movements of Scotland, Quebec or Catalonia. A more powerful challenge to this option comes from multi-national corporations. For obvious reasons corporations enjoy strong leaders that can ensure their property rights and operations throughout his country. The Italian oil giant Eni greatly appreciated its special relationship with Libya’s Gaddafi. American tire company Firestone got along famously well with Liberian warlord Charles Taylor. Chinese companies, not burdened by the pesky Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, are growing particularly enthusiastic in their dealings with third world autocrats. These companies reasonably fear that breaking up artificial states will put in jeopardy their monopolistic and monopsonistic access, as well as their property.

The left, especially those who revel in blaming any global conflict on colonialism with a capital C, generally agree with the idea of breaking up artificial states but retort that this should be done by local communities on the ground, not by world powers like the last time. But this naiveté again misses the integral problem with artificial states; their design actively undermines indigenous rights. Africa’s history is bloody with examples of violent, even genocidal responses by the ruling class to minority independence movements. Having seized power they are loathe to surrender any of it. As early as 1964, the Organization of African Unity, an anti-colonialist outfit, adopted a treaty to respect colonial borders as sacrosanct. And Pan-Arabism wanted only to amalgamate the artificial states of the Middle East into an even larger, less wieldy nation rather than realize the autonomy of ethnic minorities. It is somewhat daunting to reflect that the only entity that has meaningfully challenged the political borders of the colonial era is ISIS. But I suppose the only real argument necessary against faith in local communities achieving independence without external support is that “letterbox sovereignty” is still very much so the name of the game. Independence is achieved not when your rebellion but when Washington and Brussels starts sending letters in your name.

What can the west do? Recognizing the Kurds would be a good start. The Kurds of Iraq, numbering between 5 and 6 million, have been rebelling against central authority since even before the British Mandate, with active fighting in ‘61-‘70, ‘74-‘75, ’77-’79, ’83-’86, and the Al-Anfal genocide against them in 1988, with a casualty count nearing 300,000 and millions displaced. It was only under the U.S. imposed no-fly zone during the Gulf War on 1991 that Kurdish forces were finally able to achieve de-facto independence from Bagdad, and not until the coalition invasion of Iraq in 2003 was this autonomy formally recognized in the national constitution, though large parts of Kurd majority territory remained outside of their control. While we must not fail to acknowledge their own crimes against Assyrians and other minorities at the twilight of the Ottoman Empire, the situation of Kurds in Syria has also been one of constant oppression. They were stripped of their citizenship in 1962 and denied the right to own property, attend schools, participate in politics or have their marriages recognized. For the next two decades the central government deported them by the tens of thousands, banned the use of Kurdish place names or language, and resettled their territory with Arabs.

Given these histories, the resistance of the Syrian and Iraqi Kurds through the turmoil of the past four years has been remarkable. The prior formed a national council in 2011 and by next summer seized control of most Kurdish majority towns and border posts from the Syrian Army with minimal resistance. The region, which they recognize as Rojava, has since ratified a constitution, held elections and is in the process of forming a civil society. In Iraq, after a standoff in 2011 over oil rights and a disputed border the Kurdish Regional Government severed relations with Bagdad and is reportedly drawing closer to official independence. Their armed forces, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Peshmerga, have become the most effective fighting force against the Islamic State. Their valor is particularly commendable in comparison to the outright disintegration of the numerically superior Iraqi Army battalions in the face of ISIS assaults on Mosul and Ramadi.

Yet the ongoing international debate about the future of Syria – does Assad get a seat at the negotiating table, can Russia keep its deep-water port, will there be some form of amnesty – appears ignorant to these realities. At best, a brief point is occasionally raised about the need to include minority rights in the future constitution. But why? What rights, or any other advantage, could a Syrian constitution possibly grant to a Kurd that he or she wouldn’t have in Rojava? Or to a Druze that they wouldn’t have in Jabal al-Druze? And it is that precise fear for minorities that has Bashar al-Assad clinging desperately to power. His remaining viable objective is to prevent the massacre of his Alawite minority sect by a victorious Sunni Free Syrian Army, or worse, ISIS. A separate Alawite majority state will likely be the only way to convince him of their safety.

The same questions remain unanswered for Iraq’s future. At present, the Shia-majority federal government in Bagdad has no authority whatsoever in Kurdish regions and only over a small fraction of its Sunni population. Why reinstate it? What in the thirteen years of the supposed ‘power-sharing’ agreement since the U.S. occupation would lead an observer to conclude that there is anything worth salvaging? Free them from each other. The Ottomans, who controlled their outlying possessions through local rulers in touch with the social histories of the people they governed, wisely divided their Mesopotamian territory into the three vilayets of Mosul, Bagdad and Basra. Though the ethnic disposition has since changed to some degree, these provinces still closely resemble Kurdish, Sunni and Shia territory respectively. Perhaps in 2015 we can still learn a thing or two from history.

Now to express some reservations. I’m not here calling from the wholesale dismemberment of every Middle Eastern and African polity. In many countries the costs of doing so would outweigh far the benefits, while in others the central government’s grip is too powerful to even consider the idea. An approach that emphasizes minimizing harm would be the only way to go. But in the context of today’s Iraq or Syria, and to differing extents Libya, Yemen, and Somalia, perhaps cosmetic surgery is no longer a desirable, or even viable, option. It is irresponsible for us to deny that amputation may well be a possibility worth exploring. Treating artificial states as permanent or inevitable is at the very least intellectually dishonest. Would anybody reading this article like to argue that the Congo is anything more than a river?

Nor does anyone pretend that separation is a miracle cure; just ask the people of South Sudan. Redrawing a border will by itself do nothing to challenge the myriad issues that commonly afflict these artificial states: poverty, income and gender inequality, low human capital, weak institutions, endemic corruption, resource dependency, and so forth, and so forth, and so forth. But how can addressing these issues possibly be easier in a vast and poorly connected country than in a small, cohesive one? As to concerns that they would fall prey to foreign influence – ignoring the fact that this is already the reality of the Middle East – the opposite is more likely to happen. What cleavages could Saudi Arabia possibly exploit to fight over an independent Shiite-region of Iraq? Or what allies would Iran find in a Syria without its Alawite majority, northwest coastal region? It is that exact targeting of disenfranchised minorities that drag artificial states into regional and global power struggles.

The question of fragmentation certainly warrants deeper, and more qualified, examination. Born out of such careless and inorganic conception, it is worth considering for how much longer can, or even should, these artificial states survive for. What order and stability is there left to defend in the barrel bombed cities of Syria or the ethnically cleansed valleys of Iraq? How meaningful can armistice negotiations be if potentially the biggest obstacle to peace remains categorically off the table? One hundred years ago this spring, aristocrats drew a straight red line on a map and unknowingly condemned untold millions to their deaths. How many more must perish before we consider erasing it?

Works Cited

- (2015). “Iraqi Kurdistan: the essential briefing.” Strategic Comments 21(2); iii-vi.

- Al-Sinjary, Ziad (2014). “Mosul falls to militants, Iraqi forces flee northern city.” Reuters, (June 11, 2014)

- Barr, James (2012). “A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle that Shaped the Middle East.” Simon & Shuster (New York).

- Danforth, Nick (2013). “Stop Blaming Colonial Borders for the Middle East’s Problems: Plenty of other countries have “artificially drawn” borders and aren’t fighting. Here’s the real problem with Europe’s legacy in the region.” The Atlantic (September 11, 2013).

- De Atkine, Norvell B. (1999). “Why Arabs Lose Wars.” Middle East Quarterly 6(4).

- Easterly, William; Alesina, Alberto; Matuszeski, Janina (2011). Journal of the European Economic Association 9(2); 246-277.

- Easterly, William; Levine, Ross (1997). “Africa’s Growth Tragedy: Policies and Ethnic Divisions.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(4); 1203-1250.

- Elden, Stuart (2006). “Contingent Sovereignty, Territorial Integrity and the Sanctity of Borders.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 26(1); 11-24.

- Goldberg, Jeffrey (2014). “The New Map of the Middle East: Why should we fight the inevitable break-up of Iraq?” The Atlantic (June 14, 2014).

- Krajeski, Jenna (2015). “What the Kurds Want.” Virginia Quarterly Review.

- Mackey, Sandra (2002). “The Reckoning: Iraq and the legacy of Saddam Hussein.” Norton (New York).

- Miller, T. Christian; Jones, Jonathan (2014). “Firestone and the Warlord: The untold story of Firestone, Charles Taylor, and the tragedy of Liberia.” Frontline (November 18, 2014)

- Munya, P. Mweti (1999). “The Organization of African Unity and Its Role in Regional Conflict Resolution and Dispute Settlement: A Critical Evaluation.” Boston College Third World Law Journal 19(2); 537-592.

- Nantulya, Paul (2001). “Exclusion, Identity and Armed Conflict: A historical survey of the politics of confrontation in Uganda with Specific Reference to the Independence Era.” ACCORD Constitutionalism Project.

- Shaw, George Bernard (1904). “John Bull’s Other Island.” Brentano’s (New York).

- Swint, Brian; Shahine, Alaa (2011). “Qaddafi Advance Poses Eni Expulsion Risk from Libyan Oil.” Bloomberg Business (March 18, 2011).

- Zubaida, Sami (2002). “The fragments imagine the nation: the case of Iraq.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 34(2); 205-215.