The Year of the Black Swan

Credits: David Burnett

Credits: David Burnett

In his book,The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb describes a black swan as a highly improbable event which has major ramifications. While Taleb warns that the possibility of black swans should be taken into account, they are usually judged impossible until they become inevitable. In a historic context, the birth of Jesus, World War One, and even the 2008 financial crisis are considered black swan events. For the Middle East, the birth of Mohammad in 570, the discovery of oil in Persia in 1908, and the 2011 Arab Spring were some of the region’s most game changing black swan events. 1979 was the year when epic, unpredictable events in the game of nations changed the political constellations of the Islamic world forever.

February 1979

In response to the Siege, King Khalid did not crack down on religious extremism, but instead delegated more power to the punitive, orthodox rules of the Wahhabi religious establishment. Khalid believed that the only way to combat religious extremism was to consolidate the House of Saud’s religious ideology in civil society. Cinemas and music shops were shut down. The religious police was given greater power and nationwide gender segregation was enforced across the social sphere. The Saudis then institutionalized education policies that would breed more Islamic studies majors than finance and science majors. Many of these radicalized students would go on to join the Saudi bank-rolled Mujaheddin forces in Afghanistan.

Today, the Kingdom is at a crossroads. Crown Prince Muhammad Bin Salman, 33, blames the events of 1979 for the Kingdom’s hardliner pivot and aims to bring Saudi Arabia to the 21st century. King Khalid’s bans on cinema, music and art have been lifted. Women are now allowed to drive. The Saudi ulama and its religious police’s powers have been relegated.

However, Riyadh’s charm offensive is a red herring. The Kingdom remains an apartheid state against Saudi women, with the guardianship system stripping them of any agency over their own lives. The spread of Wahhabism continues to be a cornerstone of Saudi Arabia’s policy-making. Freedoms of speech and the press are brutally repressed, as seen with the arrests and assassinations of activists and journalists like Samar Bawadi and Jamal Khashoggi. No matter how much Saudi Arabia may try to reinvent itself, its troubled past will continue to cast a dark shadow.

December 1979

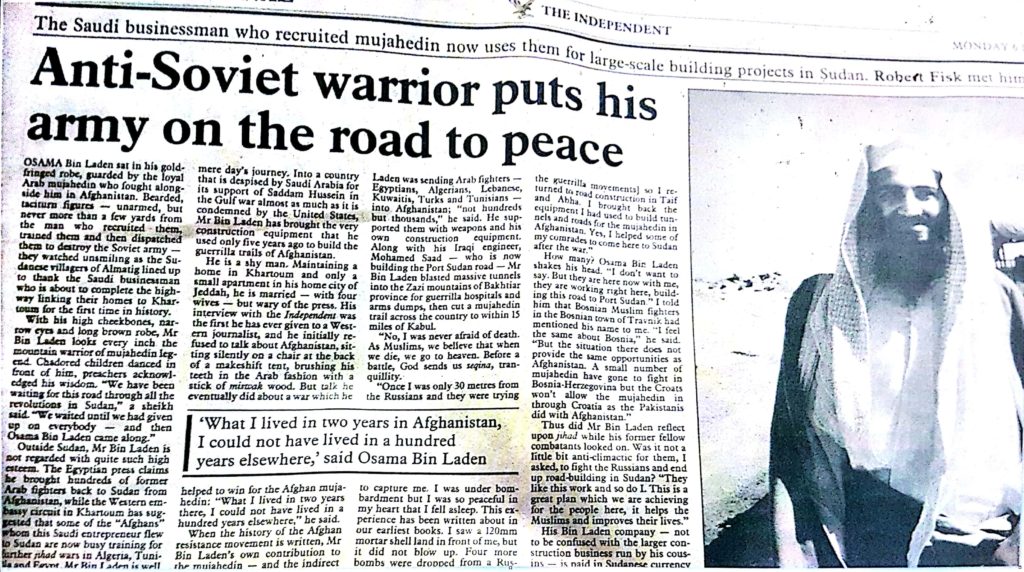

Operation Cyclone, a CIA led program in coordination with Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), came into effect in Afghanistan in an attempt to hamper Soviet invasion through the finance and arming of the Afghan Mujaheddin forces. Clerical fatwas across the Middle East called for jihad against the ‘atheist invaders,’ which caused an influx of expatriate Arab fighters to Afghanistan. The House of Saud, with its religious legitimacy questioned by the Siege of Makkah, coordinated with the CIA and ISI to finance the Saudi and Arab jihadists’ deployment to Afghanistan – including a young volunteer named Osama Bin Laden, then 22 and a drop out from a college in Jeddah.

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, many radical fighters like Bin Laden returned to their home countries and deemed regimes ‘apostates’ of Islam and ruled by corrupt secular tyrants (e.g. Mubarak, Assad, and Saddam). Soon after, the Taliban – led by ex-Mujaheddin fighters – filled the power vacuum by declaring Afghanistan an Islamic emirate and turning it into a terrorist safe haven. Osama Bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda was later responsible for the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington. The attacks led to the infamous ‘War on Terror’ and subsequent U.S invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. The Bush White House hoped to find Bin Laden and prevent Saddam Hussein from developing weapons of mass destruction. There were no Iraqi nuclear weapons to be seen and Bin Laden was only found (and killed) a decade later in Pakistan.

Al-Qaeda’s calls for international jihad spawned numerous, more violent offshoots across the Islamic world. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, the most terrifying and ambitious terrorist organization in modern history, directly traces its fundamentalist ideology to Osama Bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda. Al-Shabab has sparked anarchy in Somalia. Boko Haram has indiscriminately killed and kidnapped thousands of Nigerians.

The Bush administration miscalculated the Taliban’s military capacity and ended up dragging the United States into its worst military quagmire since the Vietnam War. Trillions of dollars of military spending, and eighteen years later, the United States has still been unable to defeat its Frankenstein’s monster. Today, the Taliban has managed to gain control of and threaten seventy percent of Afghanistan – nearly more than it did when the United States invaded in 2001. For decades, the United States and Pakistan have tried to mediate peace talks between Kabul and the Taliban. After failed U.S-led peace talks in Doha and Abu Dhabi this past year, the Taliban have now turned to an unlikely alternative. Forty years since the Soviet invasion its leadership declared fought against, the Taliban have sidestepped its former bank-rollers and are now working with Russia in peace talks with the Afghan opposition – ignoring Washington, Islamabad and the Kabul government in the process.

The Year of the Black Swan

There are moments in the human pageant when history goes fast forward, the center cannot hold, and black swans are loosened upon the world. The aftermath of the 1979 black swan events marked the beginning of the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and the fall of secularism in the Middle East; the abandonment of pan-Arabism; and the sectarian division of Islam – relationships which have since haunted the region, the Islamic world, and the international community at large.

The emergence of an Imam in Shia Islam was never thought to be possible until the end times. International calls for jihad had not occurred since the Crusades. The mere suggestion of diplomatic ties between Israel and an Arab state, let alone Egypt, would have been laughed off. The prediction of bloodshed in the courtyards of the Kabah would have warranted execution. Yet, despite the high improbability all of these events, they came true. In his 1978 hit track, ‘Eve of the War’, Jeff Wayne sang “the chances of anything coming from Mars are a million to one but still they came.”

Edited by John Weston

Special thanks to Inbar Amit

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The McGill International Review or IRSAM.inc