Three Interviews: What’s Really Going On in Venezuela?

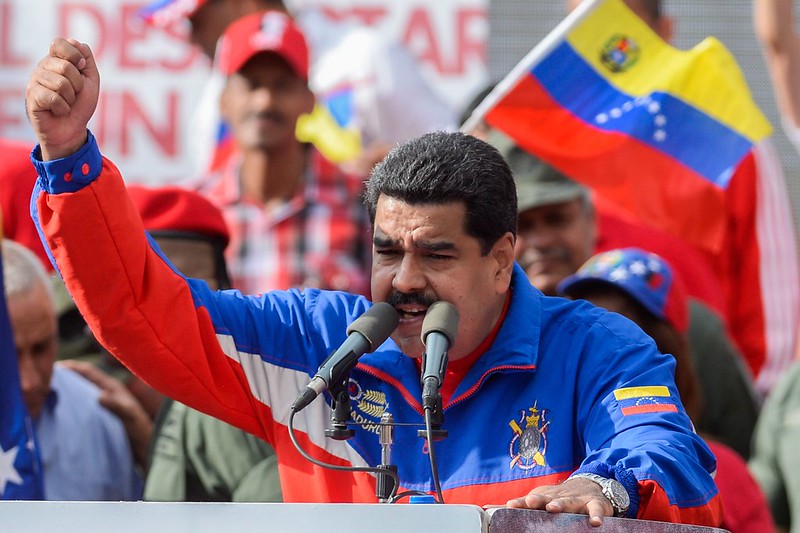

In 1999, Hugo Chavez became president of Venezuela. After Chavez died in 2013, Nicolas Maduro, a friend of Chavez and political ally, became the new head of state. Starting in Chavez’s government and worsening during Maduro’s, Venezuela has been living through a political and economic crisis that is now commonly called a humanitarian crisis.

During 2020, Venezuela’s inflation was over 1 800%, definitely well over Canada’s 2% inflation target. However, it was in 2018 that Venezuela’s hyperinflation surpassed 1 700 000%. This situation caused Venezuelans critical difficulties in accessing food, healthcare, and medicines. In 2017, over 74% of Venezuelans lost an average of 8.7 kg of weight due to food insecurity. Moreover, essential goods such as toilet paper and milk remained scarce due to the mismanagement of government-controlled prices.

Regarding the political aspect of the matter, Venezuela’s government has been branded repressive in its actions. During the 2019 protests where citizens were demanding Maduro to step down, security forces killed four people and injured approximately 200. Hundreds of people have been subject to kidnapping and torture by government officials to silence critics, remove political opponents from the public sphere, or simply cause fear. Thousands more have been victims of extrajudicial killings by the government.

At the start of 2021, more than 5.4 million Venezuelans have left their country due to the humanitarian crisis. In particular, in February 2021, the Colombian government granted legal status to undocumented Venezuelans. However, the vast majority of Venezuelan migrants have not received refugee status or temporary resident permits. I wanted to get a closer look at the people who have gone through these events. This interview contains the thoughts, histories, and hopes of three individuals who fled their country.

Ginell Parra: An English teacher in Kuwait who left Venezuela 18 years ago

MARIEL: Hi, could you introduce yourself, please?

GINELL: My name is Ginell Parra. I’m Venezuelan. I’ve been living abroad for 18 years.

MARIEL: Can you tell me about your life in Venezuela, specifically before Chavez and Maduro?

GINELL: I was born in Caracas during the 70s. Venezuela was completely different at the time. My parents worked for the Venezuelan government during the 80s, and they pursued graduate studies in the US. We were a middle-class family with a pretty comfortable lifestyle. We had two properties: the main house and a holiday home. We travelled to the US every year and visited Miami for shopping. When Chavez became president, our lifestyle started to drastically deteriorate, and with Maduro, it was completely ruined. We went from living a very comfortable life to almost living in poverty.

MARIEL: At this time, were you working or studying? If you were working, was your job stable?

GINELL: Well, when it all started, I was still a child, so I only attended school. After I graduated from university, I started working in the private sector for pharmaceuticals companies; my job was pretty stable. I moved to the US in 2002, two years after Chavez became president.

MARIEL: Can you tell me why you decided to leave Venezuela?

GINELL: I was one of the first Venezuelans to leave. When I left, almost no one had left. Most people thought that the situation wasn’t going to last for very long, that Chavez was going to step down quickly and everything would go back to normal. But I thought it wasn’t going to be that easy. What first made me consider leaving were the many companies shutting their doors and leaving Venezuela. So I said to myself, “this is just the beginning. If companies are leaving, it must be for a good reason.”

MARIEL: What’s your opinion on Maduro?

GINELL: As I said before, the destruction of Venezuela began with Chavez, but with Maduro, it grew exponentially. He is completely unprepared and has no idea how to run a country.

MARIEL: Do you think that the Venezuelan government is democratic?

GINELL: Absolutely not. For starters, elections are rigged. And there is intimidation. For example, in 2004 or 2005, there was a referendum to remove Chavez from office. Those in favour of his departure signed the Tascon list, and everyone who was on that list was banned from working for the government, which is the country’s largest employer. This is how they intimidate us. In Venezuela, there is also something known as “Carnet de la Patria,” a card that grants economic bonds, food aid, etc. It is only given to supporters of the government.

MARIEL: And why do you think that Maduro is still president?

GINELL: Because they [Maduro and his party] have accumulated power in such a way that people are afraid. I have spoken about it with relatives who are still in Venezuela. I ask them why they don’t go out and protest, and they say it’s because there has been so much repression, so much retaliation against people who protest, that they are afraid.

MARIEL: Where are you currently living, and how did you get there?

GIRELL: In Kuwait. First, I went to the US, but my mother got a job in Kuwait. I wanted to go for a while to check how things were over there, I liked it, and I stayed.

MARIEL: What do you do for a living? Would you say your job is stable?

GINELL: I’m an English teacher and examiner of international certification tests. In Kuwait, there is no stability because I’m not a citizen. I’m just a resident. At any moment, they can start a process called “Kuwaitization” and force foreigners to leave the country.

MARIEL: Would you like to return to Venezuela?

GINELL: I’d like to, but not if things stay like this. It completely depends on what happens, but looking at how things currently are, it would be really hard for the necessary conditions to be fulfilled.

Eduardo Limonche: The technician who left his family behind to work in Lima

MARIEL: Hi, could you please tell me about your life before Chávez and Maduro? If you worked or studied, where in Venezuela did you do it? And, if you had a job, was it stable?

EDUARDO: I am from the state of Carabobo, in the city of Puerto Cabello, which is Venezuela’s main port. I received an average middle-class education. I graduated from university as a technician in thermal mechanics, and I studied engineering at the University of Carabobo for two years. Before Chavez, I had a stable job at a company called IMOSA. That was my life. I was upper-middle class. With my salary, you could buy a car and an apartment within a year.

And then Chavez came along. He attempted a coup; it didn’t work. He tried again and failed again. A president pardoned him and then began his political career. When he took office, he started nationalizing companies using repressive techniques. When the company where I worked was a private company, our wages were 7 or 8 times higher than the minimum wage. The new administration was not trained. It was as if they had put a barber in charge of a major metalworking company. Of course, they started embezzling money. And then the company began to fall apart, and our lives took a 180° turn. With a week of work, you couldn’t buy bread. You couldn’t buy anything. I decided to leave then. My children didn’t have nice clothes, and they couldn’t be fed properly. It’s very sad how your life can change so drastically, so fast.

MARIEL: So, you left Venezuela because of how much your salary dropped?

EDUARDO: Yes. When the government saw a company with a good level of production and an international market, they nationalized it. And then they stole the income and paid terrible wages. Due to inflation, salaries were no longer worth anything. The minimum wage is $2 a month. How does a person with two children and a wife survive with $2 a month? It is impossible.

MARIEL: What do you think of Maduro? Do you think the government is democratic?

EDUARDO: Not at all. It’s not democratic because Maduro became president by earning Chavez’s trust. Maduro is basically filling a slot. He is president, but he doesn’t make the decisions. He’s completely surrounded by the military, and the decisions are made by Padrino López and Diosdado Cabello. They are the real presidents, and they are giants of drug trafficking. The only thing the people have left is the National Assembly, but they are silenced and can’t do anything. I know that the military is calling the shots because my cousin is a major in the National Guard, 17 years of service, and he had to leave Venezuela. If he refused to help the drug trafficking business, they would’ve killed him, so he had to leave for Chile.

MARIEL: Why do you think Maduro has been able to stay in office for so long?

EDUARDO: Because whoever is against him is thrown in jail or murdered. And because the military is by his side. Military officials are drug traffickers who have created and run a large cartel, the “Cartel de Los Soles.” That is why Maduro is still in power. People in Peru took to the streets to protest, but there was little repression. Not in Venezuela; when there were manifestations, at least 15 to 20 people died every day. And we don’t have international aid of any kind. We don’t receive any support. The Venezuelan people cannot stand up against the military on their own.

MARIEL: So the reason they are still in power is both the repression of citizens and the fact that the government is funded by drug trafficking, right?

EDUARDO: Yes, correct. They’re destroying everything, even the protected zones like Guayana and the national parks or reserves. They’re destroying it all to extract minerals like gold, diamonds, etc. because that’s also how they get their money and power.

MARIEL: How was your journey from Venezuela? Where are you now?

EDUARDO: My trip started on a Sunday. I went to the city of Puerto Cabello, which is in the centre of Venezuela, towards the Colombian border. I went through the immigration procedure in Colombia because I had a Venezuelan passport, which is a luxury. From there, I crossed Colombia until I reached Ecuador. I worked for several days in Quitumbe, and from there, I emigrated to Peru. Now I live in Lima, and, thank God, I got a job, thanks to my mechanical knowledge. I got here on June 28, 2018. I came by bus. My brother got here before me and was able to help me a little bit, but I had to work in Quitumbe to pay for my ticket. I’ve been working at the same company for around two and a half years, so it’s a stable job for me.

MARIEL: Would you like to return to Venezuela? If so, when are you planning to do so?

EDUARDO: Of course, I left practically out of necessity to support my family. My children, my wife, and my father are in Venezuela, and, of course, I want to return. For now, I am evaluating the situation. My family is there. I have two children that I have not seen in a while. If things improve, I plan to go from July to August. And then return, because I have no way to stay there.

Mariangel Leon: The woman who left everything to sell coffee on the street

MARIEL: Hi, can you tell me about your life in Venezuela, specifically before Chávez and Maduro?

MARIANGEL: Regarding my personal life, I lived in the Guárico state, the center of the country, in a town called Tucupido, José Pérez Rivas township. That’s where I come from. I went to university in the capital of my state. My province is called San Juan de Los Morros. I went to university and graduated as a public accountant. By the time I was 11, my family was financially stable. My parents worked; my dad was a bank manager, and my mom was a teacher. My life before Chavez was the best.

Chavez became president in December 1999. I was around eleven years old then, and the truth is that life in Venezuela was completely different. We had good salaries. Even low-skilled workers made enough to provide for their families. Some years we received bonuses, and we could refinish our homes. Venezuela was flourishing back then. It was flourishing in every area, from healthcare to education.

After Chávez took power, Venezuela started changing. He had a political ideology that was totally different. That was when we started to see the economy deteriorate. How did this affect us? We came from having a salary of, for example, 100 USD, which allowed us to buy everything, to having that same 100 USD and buying eighty products instead of a hundred. In 2005— if I remember correctly, I think it was 2005— he introduced a new law, without elections, with no type of consultation, allowing a president to remain in power for ten years. Then, once this law was approved, the referendums to get him out of power started. There were four in total, and none succeeded.

I started working in a gas company in 2012. It really gave you a good life, the salary was fair. I paid for my house, bought an apartment and a car. But as time passed, my salary decreased.

MARIEL: When did you decide to leave Venezuela? Did something specific occur, or were the circumstances simply unlivable?

MARIANGEL: I have always contributed to my family’s expenses, and I’ve always taken care of the wellbeing of my grandparents and my mother. I worked and what I earned covered all the expenses, and I still had some money left, but in 2018 things changed. What I earned wasn’t enough to buy my grandmother’s hypertension pills. That’s when I decided to move to Peru. That was what pushed me to make the decision; to say either I sit here and my grandmother dies within a few months, or I leave to find work. It was pretty complicated because moving meant that I had to leave everything without knowing when I was going to be back. It meant that I had to lie to my family and tell them that I’d be back in six months. And that was a lie.

When you cross the border and step into Cúcuta, that is when you realize you’re leaving your life there and starting a new one. You can be having a rough time wherever you are, have only one cent left and be sleeping on the floor, but your family won’t have to work. That is the goal many of us share. Some have children. Others don’t. I don’t, but my brother has children. They’re little two and three years old. So how can you tell a child that there is nothing to eat? And here I am. Three years away from home.

Emotionally, you have to deal with mixed feelings because your family tells you that they’re fine and that you don’t have to worry. That’s the thing, I can tell them that I’m fine, but deep inside, I’m crumbling. You lose loved ones, and you feel powerless because you’re not there.

MARIEL: Now, what do you think about Maduro’s government? Do you think that it’s democratic?

MARIANGEL: There’s nothing democratic here. From 2000 to 2020, we’ve had 20 years of dictatorship. All of the elections that have taken place over these years have been a joke. This is because the national electoral council belongs to the government. During that time, Chávez had a strong opponent, Henrique Capriles Radonski. There were marches in favour of Capriles Radonski in Caracas, and Puerto la Cruz, where I lived. I attended that march, and there were more or less 10 kilometres of people. But the election was stolen.

Many of us believe that Maduro is just a puppet. Why? Because when Chávez was alive, Maduro was part of his cabinet. There was another man called Diosdado Cabello, who at that moment was president of the national constituent assembly. However, Chávez said that he didn’t trust Diosdado to be president, so he chose Maduro instead. That’s when Venezuela fell into the worst misery that we’ve ever seen. Nowadays, the minimum wage is $2 per month, and it costs $50 to cover the basic needs of a family of five. I send $200 per month to my family so that they can buy food and medicine for my grandparents.

MARIEL: How would you explain Chávez’ and now Maduro’s strong grip on power?

MARIANGEL: The only reason they are still ruling the country is because they bought it all. They bought everything: ministries, tribunals, the national assembly, the national electoral council. Most of the population doesn’t support them anymore, but they don’t care about that.

MARIEL: Finally, can you tell me about your life now? Where are you? How was your journey from Venezuela to where you are now, and what do you do?

MARIANGEL: I travelled by land. My trip started in July 2018 with six days of bus travel — first from Venezuela to the Cúcuta border with Colombia, then onto Ecuador and finally Peru.

All of this happened on one bus, where you have to sleep uncomfortably. You eat only bread, cheese, crackers and tuna for six days. And not all of us are lucky enough to travel by bus. Some have to walk, and obviously, the journey is a lot longer, but that was not my case. I arrived in Lima by the end of July, and this is where I’m currently living. I work for Global Perú, and I was lucky to be hired without documentation, thanks to my previous work experience. It’s not easy to find a job without a temporary work permit or an immigration card. I have my documentation now, and I’ve been living here for two years and a half.

MARIEL: How long did it take to find this job? And what did you do in the meantime?

MARIANGEL: The first twelve days, I sold coffee, biscuits, cheese and cigarettes on the street from 7 AM to midnight. I was lucky to have at least a small amount of income. There were some bad days, really bad when you didn’t sell anything. I lived with some friends that helped me pay my bills for the first few days, gave me food and anything else I needed.

Then I saw an ad for the job in a newspaper, called and got a phone interview. The following week, I was told that they didn’t accept foreigners, but they ended up contacting me again to offer me a job.

MARIEL: Do you want to go back to Venezuela? If so, when?

MARIANGEL: I do want to go back to Venezuela. Not right now, because the conditions are still problematic, but I do want to. I hope that I return next year.t I’ve been away from home for a long time, and it’s time to see my family again. But God knows how long it would take for me to go back permanently. Things would need to be stable economically, politically and socially. Many people went back, and I respect their decision, but you really need to think about it. It also depends on what you are going through where you live. I have a stable job here, so for the moment, I’m not planning my return. I would like to go visit, and I hope someday I can go back for good.

Takeaways

These recollections exemplify how the economic and political failures of the Venezuelan regime have affected citizens to the point that they saw themselves forced to flee.

Ginell, Eduardo and Mariangel gave a very positive description of Venezuela before Chavez and Maduro. In particular, they mentioned that they had stable jobs that allowed them to take care of their families and even afford some luxuries. In the case of Eduardo and Mariangel, they indicated that they left when they realized they could no longer take care of their family. In particular, they indicated that the minimum wage at the time was $2 per month, and Mariangel mentioned that at least $50 is needed to cover basic needs. On the other hand, Ginell commented that she left because the economic crisis was starting. So in the three cases, we can cite economic insecurity as a cause to leave the country.

Regarding the political situation, Ginell, Eduardo, and Mariangel strongly agree with the idea that Venezuela is not a democratic country; on the contrary, they call it a dictatorship. Ginell mentioned that elections are rigged and that there is retaliation against those who voted against the regime or protested, so people are afraid. Eduardo indicated that the reasons behind Maduro’s success at maintaining power are the support of the military and the involvement of drug cartels. Mariangel called the elections a joke and pointed out that the regime has bought democratic institutions such as ministries, tribunals, the national assembly, and the national electoral council. Given all these obstacles, there are not many options for Venezuelans to protest their way to democracy.

In addition, Mariangel revealed that when she was looking for work in Lima, she suffered from job discrimination because she was a foreigner. Although non of the other interviewees commented about discrimination, a recent investigation documented more than five hundred xenophobic incidents against Venezuelans in a two-week period.

Finally, Ginell, Eduardo, and Mariangel coincide in the fact that they would like to go back home when the crisis is over. Though the future is not clear, their accounts reveal some of the most personal perspectives on what is happening in Venezuela.

Featured image by Txeng Meng is licensed for use under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Justine Coutu