To Kill a Caliph

On Sunday, October 27th, before a panoply of military flags and millions of viewers, President Trump announced that a Special Operations team had flown covertly to the Idlib region of northern Syria earlier in the day. They blitzed the compound of ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and in so doing drove him toward a tunnel, into which the terrorist dragged three of his children. It was among them, under a barrage of American fire, that he detonated his suicide vest. A monster was dead; the world, Trump gloated, could rejoice.

The president’s announcement gave rise to national celebration. Commentators and comedians alike invoked comparisons to the Obama Administration’s killing of former al-Qaeda leader and 9/11 mastermind, Osama Bin Laden, underlain by an implicit sense that the two events were comparable to begin with. But, as much as we yearn to believe that al-Baghdadi’s death is a significant blow to the future of his organization, it in fact has little bearing on the survival of ISIS itself. The Islamic State is capable of regrowing its head quickly in the wake of decapitation, and the reasons for that regenerative capacity are embedded in the structural characteristics of the organization itself.

While al-Qaeda operates as a disperse network of terror cells encamped under the noses of the weak or failed governments in places like Afghanistan and Yemen, ISIS expands as its own territorial “caliphate,” perceiving and conducting itself as a Salafist quasi-state. When it first seized vast swaths of Iraq and Syria in 2014, the organization craved a sense of sovereignty over that land, which included asserting control over its millions of residents. To that end, it cultivated a monopoly on the use of force by violently driving out any pro-Assad Ba’athists or competing Islamists that could challenge its dominance. But, with a similar immediacy, it also adopted a statist approach to governance, refraining from plundering and pillaging into oblivion and focusing instead on the provision of basic services to its newfound constituents.

As scholar Mara Revkin reported in 2016, the Islamic State cultivated a clear “social contract” with those under its control. In exchange for their loyalty, subjects of al-Baghdadi’s new “caliphate” would be entitled to the bread, water, and infrastructure that had all been extremely scarce under previous regimes. Demanded by tax collectors (notably, ones sent out from the centre to the territorial periphery), virtually all are expected to pay zakat, a charity tithe that the Islamic State redirects to its own operations. Soldiers, whose conscription is another element of the contract, are also to abide by a 20% “spoils of war” tax on that which they recover in conquerings. From those who own land, moreover, an additional kharaj tax flows into ISIS coffers. In exchange for their taxes and their fighters, ISIS furnishes the residents under its proto-sovereignty with protection from outside aggression, as well as vital resources ranging from basic healthcare to electricity. Put simply, in its early years, ISIS brought vital resources to formerly neglected areas of the Levant, and it did so by deepening its bureaucracy from within. In light of this reality, it becomes easier to understand why, in another paper from 2019, Revkin quotes Mosul residents who admit to staying inside ISIS territory because the organization was, “better than what had come before.”

Of course, this bureaucratic endeavour occurred alongside the draconian measures ISIS undertook to ensure conformity with its distorted interpretation of Sunni Islam. It remains a horrifically brutal organization, as years of terror, executions, persecution, and Yazidi genocide illustrate. Even so, the organization’s highly centralized, distribution-based governance structure bely the way in which the Islamic State seeks to engender lasting legitimacy, rather than a blunt sense of fear, among its [Sunni] subjects. That sense of legitimacy, anchored as it is in a social contract that was presided over by–but in no way predicated upon–al-Baghdadi, will not simply evaporate now that he is dead. In the bits of territory that today constitute the so-called caliphate, some variant of the contract persists–one that supersedes loyalty to the individual caliph.

What’s more, the centralized and departmentalized leadership structure of ISIS lends itself well to a swift recovery in the wake of decapitation. The group’s morale, and the bulk of its decision-making, do not rest in the hands of one man the way al-Qaeda’s originally had under Bin Laden. Instead, the group is governed by a Shura Council, a circle of militant clerics who have already selected a new leader with apparently little infighting. In an audio recording from October 31, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi was named as al-Baghdadi’s successor. Al-Baghdadi himself inherited the ISIS reins from Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, after all, and the expectation of changes in leadership has been built into ISIS propaganda for some time. With the council still formed statist institutions still in place, and the proverbial stage for a new figure already set, al-Qurashi’s appointment is a message to the world that ISIS’s existence is anything but in flux.

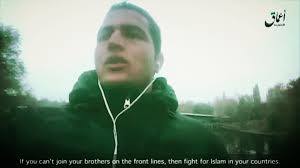

Beyond its internal dynamics, it is essential to consider what the nature of ISIS’s ethos as an organization means for its survival post-Baghdadi. Whereas al-Qaeda’s name rose to prominence in the West as a de facto consequence of the horrifying attacks it carried out, ISIS’s was designed specifically to enter the Western lexicon. Indeed, word of the Islamic State implanted itself in Europe and America in a way that seems disaggregated from the individual plots it hatches. It maintains a kind of brand, rooted in a media strategy far more sophisticated than those of any of its Salafist predecessors or contemporaries. Through online channels, it not only disseminates now-infamously gruesome execution videos and messages of incitement through its official Amaq News Agency, but also regular newsletters, tailored to instill fear in Westerns and keep supporters in the Jihadist loop. These digital structures have been integral in remedying al-Baghdadi’s absence. Just last week, for instance, 145 bot-driven accounts believed to be owned by ISIS spread audio messages of al-Qurashi around Twitter, maximizing their audience by hitching the tweets to unrelated hashtags that were trending in the Middle East. As this sort of digital damage control demonstrates, then, ISIS’s online institutions are clearly built to outlast the individual leaders that may at one time commandeer them.

This savvy use of media also figures prominently into the organization’s campaign to recruit foreign fighters to its cause–an already aggressive effort that will almost certainly intensify in the wake of al-Baghdadi’s death. According to the Times’ Rukhmini Callimachi, the Islamic State’s doctrine has become particularly prominent in France, where the neglected, largely Muslim suburbs of Paris have become fertile ground for radicalization. For these pockets, the killing of a prominent Salafist could be a calling card for extremists. President Trump’s bravado in declaring that al-Baghdadi “died like a dog,” for instance, will sound alarms of humiliation in the darkest corners of extremism, galvanizing fighters to the cause in the name of honour and vindication.

Just because al-Baghdadi’s death will not spell ISIS’s demise in itself, however, does not mean that it is not a symptom of a more gradual collapse. Indeed, the very bureaucracy that the organization cultivated as both a foundation for, and a symbol of its quasi-state legitimacy makes it vulnerable to the same stimuli that cripple actual states: military pressure and economic disenfranchisement. In ISIS’s case, the two are directly linked. As it continues to lose territory, the Islamic State loses access to oil to sell on the black market, and even more crucially, it also loses its tax base of Iraqi and Syrian residents. With both its major streams of revenue curtailed by Kurdish, Iraqi and American pressure, then, its ability for far-reaching coercion becomes strained, and its capacity to meet its obligations in the “social contract” grows tenuous. In this way, the external military corrosion of ISIS is simultaneously fuelling its internal gutting.

So, yes, the Islamic State is still receding, militarily and territorially, from its position in years past. Yet, it behooves us to disentangle the broader structural weakening of the organization from the targeted killing of its eminently replaceable leader. The latter episode–al-Baghdadi’s death–is something from which ISIS’s composition as a quasi-state enables it to recover. The former process of weakening, which is more gradual and ongoing, chips away at that very composition, and as such, erodes the group’s ability to absorb such ephemeral blows in the long-term. Thus, the killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a positive development in the world’s confrontation with ISIS, but it is far from the final development in this saga. For the moment, it seems to have been a marginal kick to an organization that won’t stay down for long.

Edited by Albert Gunnison