For Whom the Bell Tolls- the TPP and Donald Trump

Donald Trump may be a man of many words, or “the best words”, but when it comes to the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) he is certainly a man of his word. In a move that surprised few President Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP on his first day in office. In doing so he has renounced Obama’s brand of free trade economics, which had paradoxically long been the standard by which the Republican Party stood. Beyond party politics the withdrawal will potentially hurt the U.S. economy, wound American credibility, and maim America’s leverage in East and South East Asia. By signing the withdrawal he has signalled a significant change in US international economic practice, and has managed to foil his own tough talk on China. Throughout his campaign and after his election Donald Trump has made it very clear that he believes involvement in the TPP to be an unsound choice. During an address on the topic of economics in June Trump stated, “There is no way to fix the TPP… We need bilateral trade deals. We do not need to enter into another massive international agreement that ties us up and binds us down.”

https://flic.kr/p/unJvt1

During a more impassioned speech Trump likened the trade deal to rape saying, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership is another disaster done and pushed by special interests who want to rape our country, just a continuing rape of our country.” The TPP was a multilateral trade deal with 12 member states. The United States had been the one to begin and spearhead the movement—a movement which lasted a painfully long ten years. Member states were largely in South East Asia and also included Japan, the United States, and Canada. The deal emphasized lower tariffs, which considering that the United States has relatively low tariff rates would have benefited the United States and given U.S. companies easier access to these foreign markets. The TPP had strict rules against internet censoring, which would have been advantageous for internet companies and those marketing online. The deal also placed a heavy weight on intellectual property rights, environmental policy, and labor rights. Already some of the countries had started to change domestic law to match the higher standards required by the deal. In an interview with the Economist, Jayant Menon of the Asian Development Bank argued that the TPP’s reductions on government-procurement and investment restrictions would be one of the most missed aspects of the deal.

President Barack Obama had been the main proponent of the deal which even during his administration had begun facing an increasingly negative congress. There were opponents on both sides of the aisle, just as there were supporters. Bernie Sanders opposed the TPP nearly as strongly as Donald Trump did. And Hillary Clinton, while more hesitant, eventually came out against the deal as well. It seems that a vein of protectionism runs in both parties. Obama’s Pivot to Asia had the TPP as its economic bulwark. Republicans of the 90s would surely be shocked to learn that in 2017 it would be a Republican president withdrawing from a Liberal president’s free trade deal.

The TPP was the darling of think tanks and establishment partisans in the political realm. In the economic field, those who will most regret its demise are farmers, poultry and meat producers, retailers, and businesses looking to expand into Asia. The TPP had negotiated with certain countries such as Japan, which has a famously closed-off agricultural sector, to open them to foreign trade. For longer-term thinkers there was also the hope that this massive trade deal, the largest regional trade deal in history in terms of total GDP, would incentivize China to adhere to international trading standards. President Obama had brought, on a dozen occasions, complaints to the WTO concerning Chinese companies’ abuse of intellectual property rights, but the WTO failed to take a stand and China has done relatively little to change their business practices. The TPP could have acted as the carrot for China in its business practices and provided a safer economic market for U.S. companies to venture into, where there would be less concern about the risk of their product or trade secrets being copied or stolen.

President Trump has been severe in his criticism of China. During an interview with CNBC Trump claimed, “I have very big relationships with China, but the fact is China is the great abuser of the United States economically and we do nothing about it, and it would be very easy to stop.” Ahead of the Indiana primary he also reused the rape analogy claiming that China is “raping” America. Rex Tillerson has said that China will no longer be able to access the islands it has built in the South China Sea and Steve Bannon has said in the last twelve months that the United States and China will be at war within a decade. Thankfully, the disorganization of the Trump administration allows for cool heads to reign from time to time; James Mattis spent several days on a diplomatic mission to Asian countries including Japan and China, where he emphasized the importance of diplomacy and that negotiation is the way to move forward in resolving the problems of the South China Sea. However, he did conclude his trip with a strong warning concerning the East China Sea.

http://bit.ly/2kN6fcf

In cancelling the deal, President Trump has undermined U.S. foreign policy in the Pacific. Trade is not a zero-sum game necessarily; there has simultaneously been another regional multi-lateral trade deal in the works: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This deal, unlike the TPP, includes China as one of the major partners and does not include the United States — the guidelines of the deal did not match U.S. trading standards. There was no reason the two could not coexist and overlap. While it may not be necessarily zero-sum, the United States is abandoning economic and trade leadership in the Pacific region, which leaves the leadership and leverage solely to China. The TPP had been a welcomed regional addition not only for its economic benefits to the member countries, but likely also because it would have kept the United States invested in the sometimes contentious region.

While President Trump may talk tough on China, he has abandoned leverage in favour of braggadocio and has cut faith in U.S. credibility. The deal had been in the works for years, but the expectation was that the years of negotiation would have a significant pay day. Regional politicians had to make some tough sells to their constituents (in the democratic countries) and suffer at the polls. For a long time Japan had balked at opening the Japanese agricultural sector, from where Prime Minister Shinzo Abe gets many of his votes.

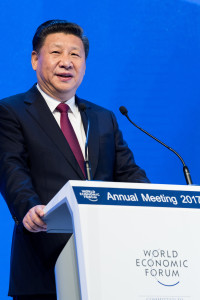

China has not been slow to read the troubled economic and diplomatic waters. In a speech at Davos on January 17, President Xi Jinping, who is also the head of the Chinese Communist Party, praised free trade and globalization likening protectionism to locking oneself in a dark room.

https://flic.kr/p/QJBLHG

All this is not to say that the TPP was devoid of faults and that there was no economic danger attached. It is possible for a trade deal with an emphasis on lowering the tariffs to favour labor abroad and for the U.S. market to face more international competition; although with its already relatively lower tariff rates, the United States would have been at a less disadvantage compared to other signatory countries. As it was an international treaty with rules and restrictions on labor and environmental policy, it would also have dictated domestic policy to states. In another article, Dylan Lamberti argues that this would consequently take away the sovereignty of the state. Additionally, by applying one economic and regulatory mold to a dozen different states, it inevitably ignores local nuances and dynamics. Amending the TPP was also designed to be very difficult; it required a unanimous decision from all member states to change regulations. However, many of the local arguments over individual state nuances had already taken place, and other states were hoping that the mold might render local economies more broadly competitive, as seen in the state-owned companies in Vietnam or the coddled businesses in Japan.

Moving forward, President Trump maintains that withdrawing from the TPP does not mean a withdrawal from the region. He has lauded the economic possibilities of bilateral rather than multilateral trade deals. Along these lines, he continues to communicate with Japan about trade possibilities. Prime Minister Abe was in Washington D.C. on February 10. Abe had previously visited the United States shortly after the election and met with Trump privately in Trump Towers. From all signs the two leaders have gotten along. Besides a handshake that went on for perhaps too long, Abe and Trump seem to have had a productive meeting. Following a series of discussions President Trump and Prime Minister Abe made a joint statement in which they, “emphasized that they remain fully committed to strengthening the economic relationships between their two countries and across the region, based on rules for free and fair trade,”. In this sense it seems that the U.S. will not entirely be extricating itself from the Pacific. However, any new, bilateral trade deals will not be on the same scale as the TPP, nor will it allow for the United States to play as much of a positive economic and diplomatic role in the larger region. Pivot to Asia, the bell tolls for thee.