Turkey’s Military: On the Outs

Protestors gather to demonstrate against the government https://flic.kr/p/fnaBtV

Protestors gather to demonstrate against the government https://flic.kr/p/fnaBtV

Outside of Ankara, construction crews work to build new military headquarters far removed from their old location next to the federal buildings. The move is one of many consequences of the unsuccessful coup attempt in Turkey last July. With fears of a military coup legitimized, President Erdoğan finally has a reason to physically distance military forces that have always been too close for comfort. The leadership’s relocation to the capital’s outskirts signals an end to its outsized influence over the president.

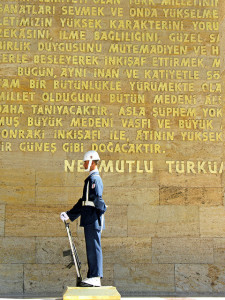

Ever since Turkey’s founding as a modern republic, its relationship with authoritarianism has been a bit cozy for the tastes of democratic observers. The country’s very founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was an unelected leader who acted quickly and often unilaterally to modernize the country. In the tradition of the country’s architect, the Turkish military continued to act independently over the decades to shape Turkish politics, generally with the aim of preventing political extremism and preserving Atatürk’s legacy. While the military has enjoyed rather gratuitous autonomy throughout the country’s modern history, its power is finally being placed firmly under the jurisdiction of Turkey’s elected civilian officials. This shift is significant; Turkish democracy is now tasked with regulating itself. Erdoğan’s increased control over his former watchdog creates a potential for increased authoritarian control and partisan volatility within Turkey.

While coups in democratic countries are destructive in their lack of regard for the electorally expressed will of the people, Turkey’s military provocateurs have often served as a counterbalance to civilian governments that overstep their bounds. The generals became a proverbial Goldilocks, removing parties deemed too leftist, too Islamic, or too antagonistic from power and writing new constitutions or holding elections.

The first intervention came in May of 1960, after Adnan Menderes’ government removed several restrictions on religious institutions, constricted freedom of the press, and eventually imposed martial law due to heightened tensions with the opposition party. A prominent general assumed power until elections were restored in 1965. Six years later, the military once again became dissatisfied with the government after the Lira suffered annual inflation of almost 80 percent and economic stagnation led to unrest. This time, the military issued the government an ultimatum instead of using force, and asked the remnants of Atatürk’s own political party to act as a caretaker government until parliament restored democracy two years later in 1973.

This intercession did little to right the Turkish economy or lighten hostilities between leftist and far-right factions, and generals found it necessary to replace the government again in 1980. While the third coup posed the greatest intrusion into civilian life, it was effective. Privatization of industry soothed economic woes and made the 1983 government a success. No further meddling was necessary until late 1997, when the Welfare Party became the first ever Islamic party to win a general election. The prime minister was prompted to resign, after making comments attacking the country’s secular constitution in what political analysts deemed a “post-modern coup”.

Due to these frequent incursions, political parties were forced to stay relatively tethered to moderation and secularism in order to keep the approval of the military. The ruling Justice and Development Party went through five different incarnations before finding a balance between Islamic conservatism that resonated with their constituents, and constraint that pleased the military. Erdoğan himself was removed from his position as mayor of Istanbul and jailed for several months for his involvement with a party deemed too Islamic. Whenever a party became troublingly extreme in any direction, democracy was suspended and then amended.

This pattern is remarkable today because of its persistence in Turkish political culture and its impending end. Erdoğan has been successfully diminishing military might since his rise to power in 2002, doling out trials and prison sentences for the planners of the 1997 coup. He succeeded in imprisoning over 300 in connection with a 2003 plot before the country’s highest court ruled against 236 of the convictions. July’s events have given him an excuse to finish it off. The army’s independence has finally been curtailed by emergency decrees giving the president power over commanders and a wide purge of anyone with suspect allegiance. While this change takes power out of the hands of unelected leaders, it does not necessarily bolster democracy.

Turkey has a fierce pride in its strong electoral system, but elections do not guarantee democracy. Over the past five years, the democratically elected president has ravaged freedoms of the press in an effort to control his party’s image and win votes. Erdoğan has called new elections when the normally scheduled ones failed to deliver his desired results, and politicized conflict in the intervening months to motivate voters through fear. Erdoğan can make advocates of democracy as nervous as the interventionist army ever has, even saying that his push for power through system changes had “precedent in Nazi Germany.” Secular schools are being closed in favor of publicly funded İmam Hatip schools that provide religious education and leave some areas without access to an alternative. Erdoğan presents an example of an elected authoritarian.

Without the military acting as watchdog, any political party could move in the direction of Erdoğan’s extremes, and the current president no longer faces significant roadblocks in his quest to gain more power. The disempowerment of generals in Ankara gives Turkish constituents more control over who comprises their government and whether they ought to be removed. It is unclear how much time remains before an extremist politician, Erdoğan or otherwise, takes it back.