Pakistan’s treatment of minorities has long been the subject of international scrutiny. The evolution of the Pakistani constitution has an ingrained precedence of religious discrimination. The name itself, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is an accurate description of who the laws are formulated to protect and favor. A microcosm of this discrimination was unveiled in front of the world with the case of a Christian woman, Asia Noreen. Her case is a manifestation of a broader problem with historical roots. Tracing the situational context is the only way to fully come to terms with the underlying systemic problems facing countless Asia’s among Pakistan’s minorities.

The Asia Case

On June 14th, 2009, Asia Noreen, also known as Asia Bibi, embroiled in a scuffle with her neighbors. Asia, a Christian mother of five, took water from a water bucket after a long day of harvesting fruit to quench her thirst. Her Muslim neighbors considered this unacceptable due to her different religious beliefs and refused to drink from the bucket. They considered her impure due to her Christian faith and hence saw the water as contaminated. Subsequently, a heated argument broke out and she was accused of blasphemy for insulting the Prophet Muhammad. Asia accused her neighbors of scheming against her and cited the case as a matter of people who didn’t like her “taking revenge”. In November 2010, she was convicted of blasphemy at a trial court in Sheikhupura and sentenced to death under Section 295-C of Pakistan’s penal code. Asia Bibi became the first woman to fall prey to Pakistan’s blasphemy laws. The decision was upheld by the Lahore High Court in October 2014, but an appeal was accepted by the Supreme Court of Pakistan in 2015. The Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and a host of other human rights organizations have singled out Pakistan’s draconian blasphemy laws for their discriminatory and unjust usage and nature.

On October 31st 2018, eight years after being convicted, Asia Bibi was acquitted of blasphemy charges by the Supreme Court. A three-judge bench headed by Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Mian Saqib Nisar, Justice Asif Saeed Khosa and Justice Mazhar Alam Khan Miankhel made the landmark decision. Never before had the Supreme Court overseen a case under this section of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws. The Chief Justice elaborated on the decision: “keeping in mind the evidence produced by the prosecution against the alleged blasphemy committed by the appellant, the prosecution has categorically failed to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt.”

The Aftermath Of The Case

The Supreme Court’s decision triggered a massive series of protests throughout Pakistan calling for the execution of Asia Bibi. Supporters of the Islamist hardline party, Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) took to the streets in major cities such as Islamabad and Lahore. They blocked roads and destroyed property worth an estimated 260 Billion Rupees (4.7 Billion CAD) in the Punjab province alone. On November 3rd, after three days of protests, the Government came to an agreement with the protesters; it included guarantees from the Government for a review of the Supreme Court’s decision, Asia Bibi being prevented from leaving the country and immediate release of the apprehended party workers and protesters. A day after the agreement, Minister of State for Interior, Shehryar Afridi, stated a Government crackdown was underway to arrest identified “miscreants” responsible for crimes and vandalism during the protests. In an apparent show of appeasement, Afridi later added that the Government would engage with the TLP in dialogue and alleged rival party activists caused much of the chaos.

The TLP registered over 2 million votes in the 2018 general election. With protests such as those following Asia’s acquittal, these radical Islamist elements have a set method of operation. Their strategy involves large scale supporter mobilization and reducing metropolitans to a standstill. The administrative concern for the government will be the precedent of one-sided negotiations. This was set by the previous administration of the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) when demonstrations against a wording change regarding the finality of the Prophet Muhammad were met with sweeping concessions. The aftermath of Asia’s trial under the new Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) government does little to stunt that momentum.

Nonetheless, Prime Minister Imran Khan pledged to stand by the Supreme Court’s decision and stated that the authority of the state would not be challenged or undermined. Asia Bibi was released from prison on November 7th but her future remains uncertain. Her lawyer claims an application for asylum in the Netherlands was submitted for Asia, her husband and two daughters. The Canadian government is also in talks with the Pakistani government over her asylum. It is difficult to fully comprehend the Asia case and its ongoing situation without understanding the nature and history of Pakistan’s controversial blasphemy laws.

History of Blasphemy Laws

These laws are not relics of a fundamentalist regime. They originate from the age of the British Raj in India and were first codified in 1860. The laws began in Christian Europe as a means to prevent dissent and enforce the church’s authority. It became a useful instrument for colonial Britain to maintain order in religiously diverse parts of the globe as they expanded their empire. Once Pakistan gained independence from British rule and separated from India, it inherited the colonial law. It criminalized numerous offences such as disturbing a religious assembly, insulting religious beliefs, and intentionally destroying or defiling a place or an object of worship.

Blasphemy laws remained in effect until 1980, when the military dictator, Zia Ul Haq, expanded them. This is when the laws took a distinct change in tone from equal protection of all faiths to a clear focus on defending only Islam. Five sections were added between 1980 and 1986; the most important of which is Section 295-C, the section Asia Bibi was initially convicted under. Section 295-C relates to a specific set of offenses: “Use of derogatory remarks, etc., in respect of the Holy Prophet”. The section poses a unique dilemma in that it is the only blasphemy provision with a mandatory death penalty.

One of the sections explicitly targets the Ahmadiyya community, a maligned and persecuted Muslim minority. Section 298-C stipulates “Person of Quadiani group, etc., calling himself a Muslim or preaching or propagating his faith” as a punishable offence. The point of contention is that Pakistan’s Sunni and Shia Muslims believe that the Prophet Muhammad is the final prophet from God whereas the Ahmadi Muslims do not. This disagreement has lead to most Shia and Sunni Muslims to consider the Ahmadiyya as outside the bounds of Islam.

Zia Ul Haq also formed a separate judicial branch, the Federal Shariat Court, to review and amend laws deemed contrary to the teachings of Islam. These measures were an integral part of his strategy of Islamisation to reform the country based on Islamic law during his dictatorship from the mid-1970s to the 1980s. From this era, the scope of the blasphemy problem in Pakistan intensified. Only ten blasphemy cases were heard in court from 1927 to 1985. From 1987-2012, the National Commission for Justice and Peace says 1,058 cases of blasphemy were registered. Of the accused, 456 were Ahmadis, 449 were Muslims, 132 were Christians and 21 were Hindus. A concerning 57% of those accused of blasphemy hail from the 4% of Pakistan’s religious minorities.

To date, no one has been executed under Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, although at least 65 have been lynched or murdered since 1990. In April 2017, a student, Mashal Khan, was dragged out of his university housing by a mob of hundreds of students. He was beaten, shot and his body subsequently mutilated. Mashal was accused of harboring “anti-Islamic” views, although a police investigation after his murder found no evidence of such a case. ICJ’s 2015 study on the implementation of blasphemy laws in Pakistan stated over 80% of convictions are overturned on appeal due to evidence fabrication and lack of proof. The religious discrepancy and the acquittance rate lend credence to those who argue that the laws are tools for oppression and personal vendettas.

Reform and Resistance

Opposition to the blasphemy laws and calls for reform over the years have invoked mass public outrage and political violence from the conservative Muslim base and its radical extremist fringe. A Pew Research Center poll from November 2011 showed that 75% of Pakistani Muslims say blasphemy laws are necessary to protect Islam in their country, while only 6% say blasphemy laws unfairly target minority communities. This highlights that public support is a limiting reagent for law reform. International pressure for reform of the laws has been met with widespread public disapproval. Calls for the repeal of the law from the Vatican under Pope Benedict XVI in 2011 lead to mass demonstrations in support of the law. For this reason, all political parties are hesitant of antagonizing the conservative Muslim base and fringe religious elements such as TLP. For instance, in 2011, Sherry Rehman, an MP at the time and a vocal advocate for blasphemy law reform, dropped her efforts after accusing her party, the leftist Pakistan People’s Party, of giving into extremist pressure. The fundamentalist and Islamist elements sprouting from the country’s overwhelming 96% Muslim majority leaves little room for political traction to protect the country’s minorities.

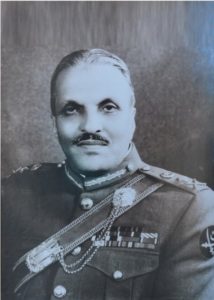

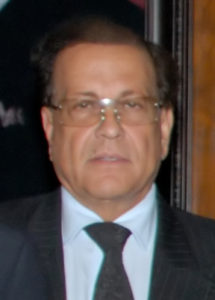

Some prominent voices that rose up through the canyons of silence included those of Salman Taseer, former Governor Punjab and former Minorities Minister, Shahbaz Bhatti. Both men were part of the Government during the Pakistan Peoples Party’s tenure from 2008 to 2013, around the time of the Asia Bibi case. Both opposed the blasphemy laws, decried their misuse and publicly showed support for Asia. In March 2011, Bhatti, the only Christian member of Cabinet at the time, was shot dead by gunmen who ambushed his car in the capital. In January of the same year, Salman Taseer was murdered in the same city by his own bodyguard, Mumtaz Qadri. Qadri was hanged in 2016 and his funeral was attended by thousands honoring him as a hero for his actions. The hanging took place on February 29th so the leap year would disrupt potential future annual demonstrations. TLP itself was formed by founding Chairman Khadim Hussain Rizvi to call for the release of Qadri before his hanging.

The Future

The reigning PTI party had called for a review of blasphemy laws in 2013 when they sat in the opposition. For their successful 2018 election campaign, however, PTI restructured their message to gain a foothold in the conservative strongholds of the PML-N in Punjab. Khan subsequently defended the blasphemy laws during the campaign. It is unclear where positive reform can sprout from given a lack of public support and a lack of political appetite to resolve such a sensitive issue. The global outrage and condemnation of the laws by human rights organizations are simply screams into an empty echo chamber with no escape in sight. It remains clear however, that until these draconian laws are repealed or reshaped that Asia Bibi’s case will remain a drop in an ocean of religious intolerance and constitutionally supported discrimination.

Edited by: Helena Martin and Sarie Khalid