Does the US have a human rights problem?

July 16, 2015

"In July the President became the first sitting President to visit a federal prison. Here the President departs El Reno Federal Correctional Institution in Oklahoma with Valerie Jarrett and Secret Service agent Rob Buster." (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

This official White House photograph is being made available only for publication by news organizations and/or for personal use printing by the subject(s) of the photograph. The photograph may not be manipulated in any way and may not be used in commercial or political materials, advertisements, emails, products, promotions that in any way suggests approval or endorsement of the President, the First Family, or the White House.

July 16, 2015

"In July the President became the first sitting President to visit a federal prison. Here the President departs El Reno Federal Correctional Institution in Oklahoma with Valerie Jarrett and Secret Service agent Rob Buster." (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

This official White House photograph is being made available only for publication by news organizations and/or for personal use printing by the subject(s) of the photograph. The photograph may not be manipulated in any way and may not be used in commercial or political materials, advertisements, emails, products, promotions that in any way suggests approval or endorsement of the President, the First Family, or the White House.

The United States is often seen as a world leader in negotiating international treaties and agreements, including the crucial UN Declaration of Human Rights. However, the U.S. is the only developed country that has not yet ratified numerous human rights treaties including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. On the other hand, the U.S. State Department website states that human rights are fundamental to the mission of the state department. Furthermore, US Presidents often condemn countries like Russia and China for their human rights abuses. The actions alone illuminate the complicated relationship that the United States has had with human rights and while the state of human rights in the U.S. is not comparable to the state of rights in the aforementioned countries, the U.S. has continually failed to stay true to its own commitments. This article will focus on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations in 1948, which outlines 30 articles as “a common standard for all peoples and nations” and how the UDHR can be applied to American domestic issues.

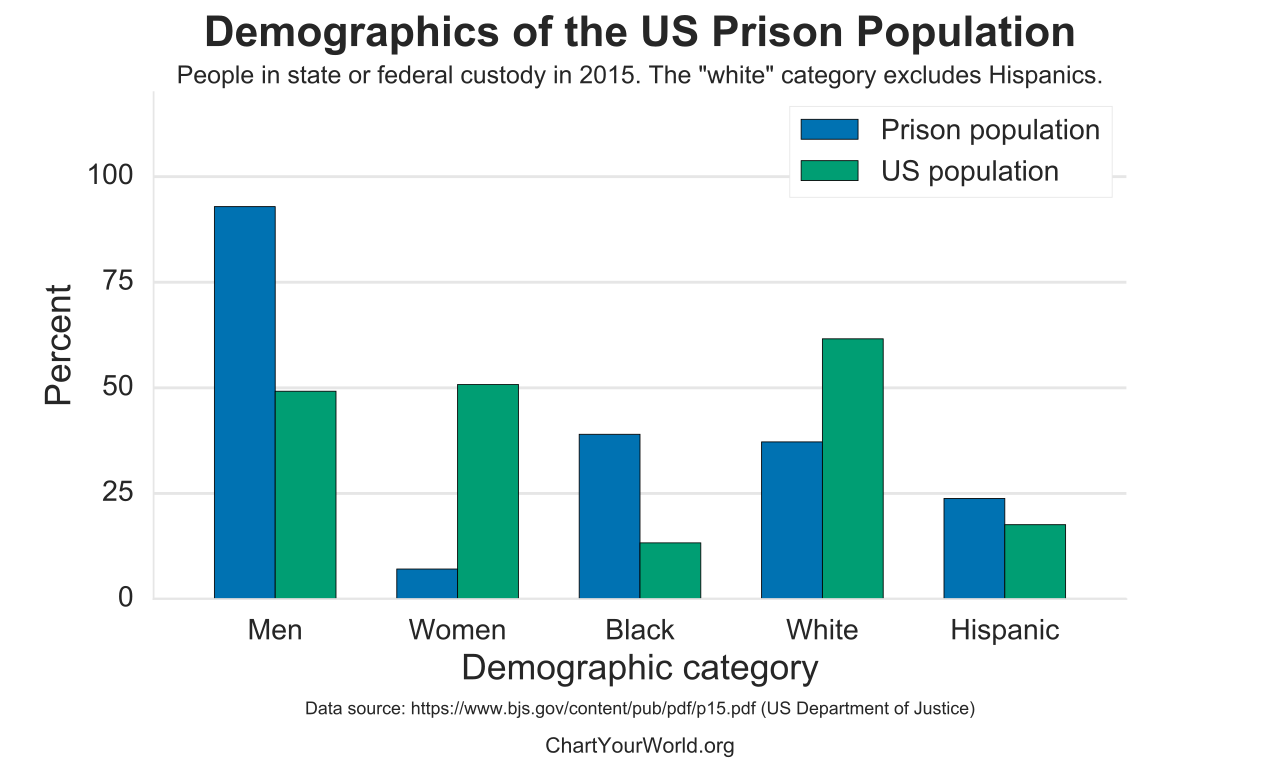

U.S. human rights issues, especially those surrounding mass incarceration and the criminal justice system, have been a concern of groups like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Human Rights Watch, and the UN. The U.S. has the almost the highest rate of incarceration in the world. Enforcement in the criminal justice system ostensibly contains racial biases, inhumane incarceration policies, and the permanent branding of prisoners after they have been released, which succeeds in disenfranchising large swaths of the U.S. population. The U.S. has also failed to commit to providing basic needs such as food and water in places like Flint, Michigan, and Puerto Rico.

Bias in the criminal justice system is wide-spread and begins with arrest. Police presence in the U.S. is disproportionally located in minority neighborhoods and police training fails to equip policemen with the requisite training and tools to effectively handle tense situations and counteract implicit bias. These policies result in increased arrest rates for black and Latino populations. But this is only the beginning of the “the racial disparity that permeates every stage of the United States criminal justice system, from arrest to trial to sentencing”. This U.N. report, featured by the Sentencing Project, an organization working for a better criminal justice system, observes that “The United States in effect operates two distinct criminal justice systems: one for wealthy people and another for poor people and minorities”.

Within this framework, the increased likelihood that neurodivergent individuals will die at the hands of police is especially concerning. According to a report by the Treatment Advocacy Center, “at least half of people shot and killed by police each year are mentally ill“.

Not only is this counter to the idea of equal protection in the U.S. Constitution, but it actively creates an environment in which certain parts of the population cannot rely on the protection of the criminal justice system. It specifically violates the UNDHR articles protecting the right to security of person, equal protection, and arguably protection against arbitrary arrest and the right to a fair trial, which are not guaranteed in a racially biased system.

Within U.S. prisons, the conditions and policies can be extremely

traumatic and exploitive. Solitary confinement is common for adults and juveniles and has been considered a human rights abuse, violating the Convention on Torture and often leading to trauma. Furthermore, only this August were women in prison guaranteed menstrual products. Previously, many female inmates had to ration the same product over several days. Additionally, many prisons employ some system of forced labor where corporations are allowed to pay workers between .33-1.41 dollars an hour to do manufacturing and farming jobs. In fact, many of the American-made products that are lauded as supporting American industry are actually made in prisons, including items from Whole Foods, Victoria’s Secret, and the US Military. This is, in part, a result of the privatization of American prisons, encouraging corporations running prisons to profit however possible. The American system strips prisoners of their humanity, violating their basic economic and social rights, and often leaving them much worse off than when they entered.

For many, the consequences of going to jail or even just being arrested continue once they have been released. America prides itself on upholding democracy, but convicted felons often lose the right to vote for at least the length of their sentence depending on the state. Their crime can range anywhere from marijuana possession to murder. Not only does this system disenfranchise many citizens, but because of racially biased policing, it disproportionately affects black men. Additionally, many states allow discrimination against job applicants based on their felony status or whether or not they have been arrested. These laws prevent equal social and economic opportunities and violate the right to work and right to participate in the government protected by the UNHDR.

It almost seems that once someone has been arrested, they no longer deserve the fundamental rights that the U.S. Constitution supposedly upholds. The Bill of Rights, in fact, includes provisions that make prison labor legal. The 13th amendment outlaws slavery “except as punishment for a crime“.

But even beyond the criminal justice system, the U.S. has left Flint, Michigan without clean drinking water since 2014. During a switch in water sources officials failed to apply anti-corrosive agents, resulting in lead-contaminated water. Flint officials failed to properly inform residents or take swift action, resulting in water shortages, doubling blood-lead levels in children, and nine deaths from related diseases. A resolution in Flint has still not been reached and there are almost 3000 areas with double the lead contamination of Flint’s water across the United States. Furthermore, after this year’s hurricane season, Puerto Rico was left without water and electricity and only on October 16th did 72 percent of residents have clean water. While the vast majority of communities have access to clean water in the US, it is important to not overlook those who do not, as the lack of potable water is often a symptom of greater neglect.

On top of that, indigenous people in the United States lack equal access to education, employment, and healthcare especially on tribal lands. The 78 percent of Native Americans living off tribal lands face disproportionate poverty, and are much more likely to end up in the foster system; 56 percent of indigenous women have experienced sexual violence, 70 percent committed by non-native men. These consequences are a result of policies designed to eliminate and assimilate the native population that continue to marginalize indigenous communities. Lack of access to equal protection, the right to self-determination protected in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Populations, and tribal lands without equal access to healthcare and employment are all UN human rights violations. On top of these conditions, the U.S. has yet to acknowledge and educate its population on the history of its genocide of Native Americans.

What is notable about all of these human rights violations is that they are not a part of the mainstream political discourse in the United States. While many ostensibly progressive western countries do not have perfect human rights records, they should make it a priority to uphold the beliefs they have established for the rest of the world to follow. One of the issues at the heart of this discourse is that many Americans disagree with the premise and importance of human rights violations, which is then reflected in the Senate’s reluctance to ratify many of these treaties. Issues such as same-sex marriage, equal access to healthcare, torture of prisoners and the death penalty are widely seen as political disagreements rather than human rights issues. Arguably, much of this resistance to adopting international treaties has also sprung from isolationism and concerns about sovereignty. However, the world is becoming increasingly interconnected, with many countries in the Americas and Europe, including the United States, using international law as precedent domestically, suggesting that the ratification of these treaties is not an inherent threat to sovereignty.

It is about time that the United States comes to terms with its human rights issues, and that begins with bringing these issues into mainstream political discourse. By no means is the United States on par with autocratic repressive regimes, but it is time it begins to work towards the higher standards it supposedly holds itself and others to on a domestic level.

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo