Walking the Line of Justice and Stability: East Timor and ASEAN

https://www.presidenri.go.id/foto/presiden-jokowi-dan-pm-timor-leste-bahas-peningkatan-kerja-sama-ekonomi-kedua-negara/

https://www.presidenri.go.id/foto/presiden-jokowi-dan-pm-timor-leste-bahas-peningkatan-kerja-sama-ekonomi-kedua-negara/

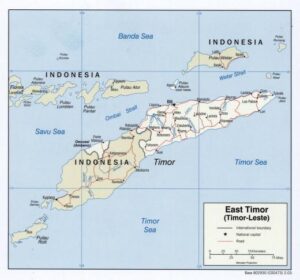

East Timor (Timor Leste) is a small Southeast Asian nation that makes up the eastern half of the Island of Timor. The Western half belongs to Indonesia, from which East Timor gained independence in 2002. Previously, Timor was a Portuguese colony from the 18th century until 1975. According to the Reporters Without Borders Freedom Index East, Timor was ranked number 10 in the world for freedom of press. They have been democratically ruled since their independence, and place great emphasis on freedom of speech, relative to other countries in the region. Even as it has prioritized press freedom, East Timor’s economy has struggled to develop, growing at a rate of 3 per cent in 2022. Overall, the economy has experienced three years of negative growth in non-oil real GDP in the last five years. This means that the government’s oil fund and spending of revenue from this fund have sustained their GDP in recent times, but outside of this support, the economy is struggling. Timor’s recent financial success is “reliant on government spending and revenues from natural resources”; this is not an ideal economic situation. According to the World Bank, short and medium-term strategies are urgently needed for East Timor to be a sustainable economy. One of the primary solutions proposed by the World Bank is a call for “diversification of the economy through development of export sectors essential for sustained growth” in East Timor.

What Joining ASEAN Means

ASEAN membership has been a primary goal of East Timor’s government for many years. Their initial application was submitted in 2011, and they were granted observer status in 2022 with no official benefits. So if granted full membership, what would these benefits entail? ASEAN facilitates a free trade agreement between its members, which allows for reliable, cheap trade within the region. ASEAN membership also comes with a security agreement allowing for military assistance through other members in stabilizing trade. This security agreement is particularly important for a small nation such as East Timor, especially with trade routes experiencing mounting tension along the South China Sea, one of the most traveled routes for ASEAN nations trade. This membership would greatly benefit their ability to trade which, as mentioned, is at the top of the list of the World Bank’s solutions – “diversification of the economy through development of exports.”ASEAN nations are projected to have some of the fastest growing economies of any region in the world over the next 25 years. For background, if the current ten ASEAN member states were one economy, it would be the fifth largest in the world with a combined GDP of $3.3 trillion USD (2021). Because of its projected growth, there are competing foreign influences in this region, namely the United States and China, which creates the possibility of healthy economic competition for ASEAN, so long as there are no further military or economic challenges. escalations regionally. To be a part of this economic alliance means greater interest in American and Chinese foreign investment. The expectation is that ASEAN is a quickly developing, emerging economic region and for East Timor to be left out of the coalition would hinder their future development opportunities. However, a possible point of contention for East Timor’s membership in ASEAN is that most of the member groups in ASEAN have high levels of censorship and few of them are openly democratic countries contrary to East Timor values.

Additionally, ASEAN has a policy of “noninterference” meaning their number one collective priority is to bring stability to the region and not to interfere in other member nations’ domestic policies or politics. This policy of noninterference also goes for broader geopolitical concerns. For example, with the rising tensions between the US and China in the region, most ASEAN nations decided to not interfere or pick sides, rather they try to benefit themselves by putting the two larger nations against each other.

Myanmar Conflict and ASEAN Response

An illustration of the tepid ASEAN support for democratic principles and human rights protections is apparent through Myanmar. Myanmar has had multiple different changes of leadership over the last decade. Most recently in 2021, the democratically elected leaders had power ceased from them by the military Junta. Since this change in power, there has been an ongoing civil war between the military and rebel groups. There have been widespread violations according to the UN and various human rights groups. Ethnic genocide is being conducted by the military against the Rohingya ethnic group in the South West region of the country. According to Human Rights watch, 1.3 million people have been displaced since the coup in 2021 and 80 per cent of all townships in the country have been affected by combat.

Despite the non-interference policy, ASEAN has come up with the “five point consensus” which is a plan of de-escalation aimed at Mynmar’s military leadership. This plan has been rejected by the government of Myanmar and largely ignored. There has been very minimal retaliation or follow up by ASEAN member states except to the extent that there has been a ban on Myanmar leaders from meetings. East Timor wants more than a proposed plan to respond to the junta in Myanmar. Current ASEAN member nations are far more reluctant to push any further given their own soft support of democratic values and the group’s historical grounding in a policy of noninterference. Basically, ASEAN has condemned Myanmar diplomatically but ASEAN’s actions suggest they are just looking the other way.

A Possible Shift in ASEAN led by East Timor

Because ASEAN is run on a policy of non-interference in domestic affairs, it has traditionally been a group that prioritizes regional stability and economic growth. East Timor is a nation that runs on democratic principles and maintains that justice should be considered a priority, willing to risk ASEAN membership to support and stand by their values. This offers a clear statement not only on Myanmar’s violence, but also a statement on ASEAN and its lack of reaction to that violence. As well as a statement to the international community and their deferral of action to ASEAN. If entire ethnic groups and populations can be oppressed by military regimes while the world turns a blind eye, who is there to stop that from happening to any other small nation or group? East Timor sees the five point consensus as performative rather than action oriented. As stated by lecturer of Political Science at Universidade of Nasional Timor Lorosa’e Li Li Chen, this move by East Timor is not just a condemnation of violence against an aggressor rather, “it should be understood as a political proposal for an alternative ASEAN order, where all member states and individuals are able to endorse and embody plurality and coexistence of values freely in spite of member states’ different prioritizing of values.” East Timor is weighing its options, but overwhelmingly believes admission to ASEAN is not as high of a priority if the coalition has no ability to effectively stand against regional injustices.

Edited by Nicole Kastanias

Featured Image: Former Prime Minister and President of East Timor Taur Matan Ruak Arrives at Meruorah Hotel, Labuan Bajo for East Timor’s first ASEAN summit with “observer” status. Photo from Press, Media and Information Bureau of the Secretariat of the President of the Republic of Indonesia (BPMI Setpres / Muchlis Jr) This image is in the public domain according to Law of the Republic of Indonesia Article 43 of Law 28 of 2014 on Copyrights.