We’re Getting There

Hope for the Future of Climate Activism

Protesters march during the Cop 15 climate summit in Copenhagen -Kris Krüg https://bit.ly/2UPbls2

Protesters march during the Cop 15 climate summit in Copenhagen -Kris Krüg https://bit.ly/2UPbls2

For more detailed coverage of the March 15th Climate Strike in Montreal, Check out this article by Alexandra Yiannoutsos.

In Montreal, there seems to be a manifestation every other day. On Sherbrooke Street, Parc Avenue, around Place-des-Arts and Saint-Catherine’s, hundreds of people block traffic, attract gazes, and scream their hearts out. But this is a different story. On the 15th of March, 150,000 students reclaimed the downtown core from gas guzzling cars and silenced their engines to raise their own voices. Thousands of students led and organised these marches, from small towns to big cities. As a result, a total of 1.5 million people around the world came out, and Montreal claimed the crown as the largest strike of them all. These students were inspired by the school strikes of a lone teen in Sweden, all with the same message: it’s time for system change, not climate change.

Despite the massive numbers of students marching through the streets, followed by endless media attention and waves of Facebook posts and tweets, there is often a counter wave of skepticism; a lack of enthusiasm for what anyone expecting youth apathy would have viewed as a magnificent achievement. They believe that the protests will be ignored, that the participants will just go home and continue to live their over-consumptive lifestyles, and that individuals will never sacrifice their own lifestyles for the planet.

These are all valid concerns. Canada has the fourth largest ecological footprint per capita, and if everyone lived like the average Canadian we would require 4.7 copies of our planet. On top of that, as a country that continues to invest in fossil fuel expansion, we may not even be the best role models for such a movement. But that is more of a reason for students to get out, to bring the necessary change to ourselves to become better role models for the world. We have a greater responsibility to change, and this march, just like any other example of collective action, is a start. It only takes a quick look through the history books to see how activism has shaped our lives.

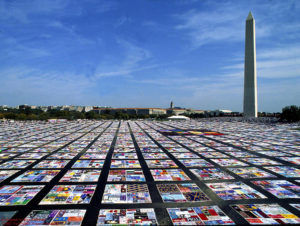

Take the HIV/AIDS epidemic as an example. In June 1981, the U.S Center for Disease Control (CDC) published an article outlining a series of cases of failing immune systems in five men in Los Angeles. This was the first official reporting of the disease which would grip the entire world for decades. Within months, people began organising to discuss this new epidemic. Service providers such as the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) were founded to counsel inflicted individuals, and LGBTQ+ communities began to organise to provide support and information.

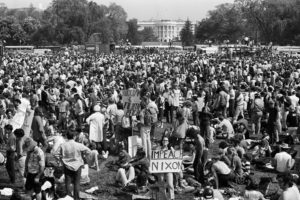

After limited progress from the government’s response, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power was founded in 1987. The group began as a civil disobedience activist group, staging protests on wall street and in churches, shutting down the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and marching on the White House. In addition to their fieldwork, they hosted workshops, explaining the intricacies of the disease and the pharmaceutical response to those willing to learn. These acts of civil disobedience took place to attract attention to the situation, and once this attention was drawn they used their powerful understanding of the situation to successfully bring change.

What started out as a civil disobedience movement morphed into a movement that composed of activists turned experts in their field. A similar thing can be said about the Anti-Vietnam War Movement. The movement went through four distinct phases: education, peaceful protest, civil disobedience, and then becoming a political force. It would not have been successful with only one or the other. Bystanders see these activists take to the streets. They hear the chants and catchphrases, their demands, and their knowledgeable and articulate speeches. As people learn more about an issue and understand why people are passionate about it, it translates into votes. Such power is not unknown to politicians and executives.

In the same way, climate activism can act as the foundational base for real change through the levers of government. It is important, especially in democracies, that the breadth of the populace shows its support for a movement, as it signals to those in power to make the change to follow through. Without this, legislation can fail, and this can be seen through the US attempt at cap and trade in 2010, as well as with the backlash towards Macron’s carbon tax. Policies like Macron’s put the environment ahead of the people, pulling a leg off of an already shaky stool. In the US, groups like the Sunrise Movement are doing much more than what most of the public actually get to see. Behind the actions and the rallies, these groups mobilise the power of thousands of people to educate and discuss viable solutions with politicians. Spearheaded by a dedicated set of youth, the organisation has worked directly with politicians to win support in Congress, and are one of the leading sponsors of the Green New Deal. Such groups show that the success of these sweeping policy changes requires action by the government and collective action by the people.

Support for solid policy can and should come in many forms. Support comes from the actions of individuals, transforming their own lives but also pushing to transform their societies, and they come from collective action, amplifying the conversation to spread knowledge, little by little. Popular movements that seek to combine education with pressure are a necessary base, especially in something so fundamentally misunderstood and polarizing, yet impactful, as climate change. It may not seem to be the most effective means on the surface, but deep beneath the waters lies an army of changemakers that are hoping for a future. In the face of such an existential challenge, what else is there left to do?

Edited by John Weston