What the United States could learn from the French intervention in Mali

In 2012 a Tuareg organization, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) unilaterally declared the independence of Azawad, a territory in the North of Mali, which allowed fundamentalist groups, in a not-so-new turn of events, to hijack the situation and take control of the war-torn region.

In 2012 a Tuareg organization, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) unilaterally declared the independence of Azawad, a territory in the North of Mali, which allowed fundamentalist groups, in a not-so-new turn of events, to hijack the situation and take control of the war-torn region.

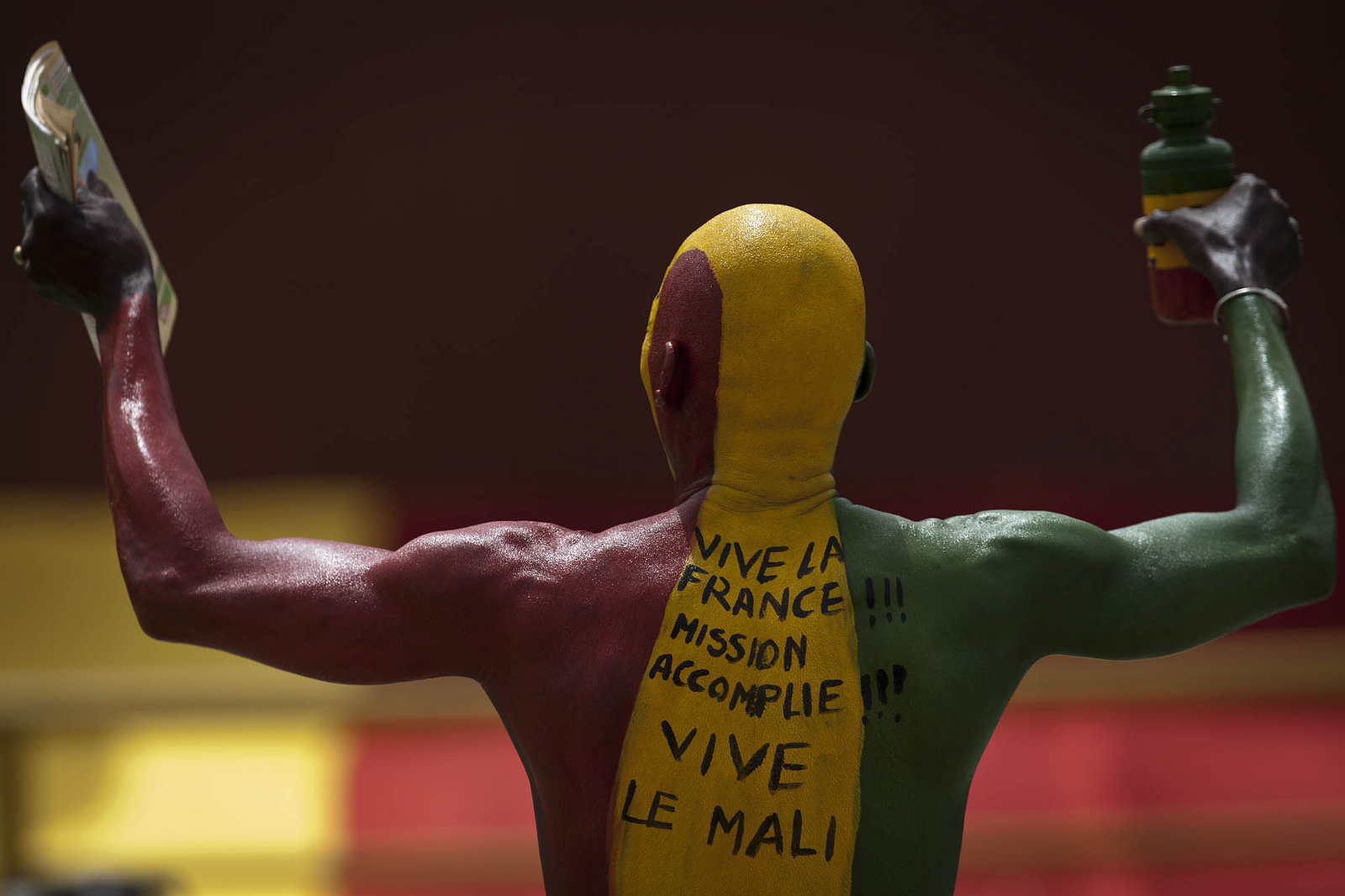

Following an official request by the Malian government and the unanimous adoption of U.N.S.C Resolution 2085[i], Mali has been the tenth country in which a Western power – in the last five years – has intervened militarily against Islamic fundamentalist groups. Yet, unlike during the interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Yemen, 96% of Malian locals were favorable to a foreign military presence[ii] under operation Serval. Moreover, the French military succeeded in dislodging al-Qaeda-backed militants in Northern Mali, with a fairly small force of 4,000 deployed troops and in rather short time span of nineteen-months.

As such, the United States could learn much from Operation Serval, a campaign whose name reflects certain key requirements for the success of a counter-insurgency operation. Indeed, the serval is a sleek and fast desert cat that hunts alone, relentlessly tracking its prey through the desert, before snatching it from under the rocks and promptly leaving.

“First to enter and first to leave” in order to avoid a costly and long-lasting military campaign[iii] has been the golden rule of Admiral Édouard Guillaud, Chief of Staff and Commander of the French Forces in Mali. The longer a combat force stays abroad, the more it is seen by locals as an occupation force, increasing resentment and counter-productively fueling insurgencies[iv]. Nevertheless, such a swift and immediate deployment would not have been possible without the leeway and freedom of action given to the military by French political leaders. Indeed, “the French political system, in contrast to Germany’s for instance, allows immediate military action”[v].

Once on the ground, the French showed great aptitude at quickly deploying small yet effective forces without contorting units to “remain below an arbitrary political troop cap”[vi]. Moreover, the French military’s traditional preference for rapid maneuvers allowed them to place a tactical preference on mobility over protection[vii], a choice that the U.S. Marine Corps has regretted not making as they now strive to reclaim their role as an expeditionary force[viii]. There is a difference between an “armored force that is fantastic at defeating [Soviet] T-80s crossing the Fulda Gap” and one able to rapidly maneuver in mountainous valleys to fight an asymmetric insurgency.

‘Work together, supply together, but fight alone’ could be the second golden rule of the intervention in Mali. For Colonel Michel Goya, Operation Serval owes its success to the freedom of action granted by operating independently from NATO or EU processes[ix]. In Afghanistan, for example, “some countries fought whilst others took a backseat”, which makes coalition operations harder to organize and more prone to running into problems[x]. Adding to the complexity of operating within a coalition, each member of ISAF in Afghanistan or the Multi-National Force in Iraq had its own complex, intricate, and sometimes crippling rules of engagement and caveats. In Mali, on the other hand, France took on the main fighting role, whilst eleven countries, including the United States, Canada and the U.K. provided non-combat support, mainly through the provision of transport aircraft and support personnel.

The third and fourth golden rules should be “know when to stop and what to be content with”[xi] and ‘let soldiers fight and peacekeeper keep the peace’. Once strategic objectives were met, France pulled out its troops and let Malian forces and its African allies take the lead in the long-term campaign to oust al-Qaeda, MOJWA and Ansar Dine from the Sahara and Sahel deserts. The exit is incontestably the hardest phase of a counter-insurgency operation, as it immensely difficult to transform short-term military triumphs into long-term political achievements[xii]. Yet, here again, France seems to have escaped the strategic stalemates encountered in Iraq and Afghanistan perhaps due to a more material, and less intellectual approach.

U.S. troops in Afghanistan and Iraq have had both combat and police roles all whilst having to justify ‘why they are here’[xiii]. As military analyst Thomas Barnett noted, the U.S. military has been “shooting insurgents in the morning and handing out aid in the afternoon”, instead of accepting the dichotomy between warfare and peacekeeping[xiv]. On the other hand, the French have let those who fight, seek out and crush the enemy – and to do so alone – and those who do peacekeeping rebuild infrastructure and win the hearts and mind of the people within a large and inclusive coalition. Once Operation Serval came to an end in July, France launched Operation Barkhane along side Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Mauritania and Chad to consolidate political and military achievements. At the same time, French and EU advisors were sent to train local security forces, and equipment was sold and donated to local governments to help them secure a peaceful outcome.

Therefore, although the achievements of Operation Serval do not provide insight on how to handle intense conventional conflicts, they have offered invaluable lessons on the successful conduct of counter-insurgency operations – lessons that could be more than useful in Afghanistan, Yemen and now Iraq and Syria.

______________________________________________________________________

[i] United Nations. Security Council Resolution 2085. 2012. <http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2085(2012)>.

[ii] “Interactive: Mali Speaks.” Al Jazeera (2013): Do you think France should have intervened in northern Mali? And why?

[iii] Adam, Patricia. Assemblée Nationale. Commission de la défense nationale et des forces armées. Audition de l’amiral Édouard Guillaud, chef d’état-major des armées (CEMA), sur les enseignements de l’opération Serval. Paris: 2013.

<http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/cr-cdef/12-13/c1213074.asp>.

[iv] Walt, Stephen. “Top 10 Lessons of the Iraq War.” Foreign Policy. 20 Mar 2012.

[v] Delaporte, Murielle. “French Lessons From Mali: Fight Alone, Supply Together.” Breaking Defense. 17 June 2013

[vi] Maj. Gen. Olivier Tramond, , and Lt. Col. Philippe Seigneur. “Early Lessons From France’s Operation Serval In Mali.” Association of the United States Army.

[vii] Shurkin, Michael. “France’s War in Mali Lessons for an Expeditionary Army.” RAND Corporation

[viii] Brannen, Kate. “Mobility Vs. Survivability.”DefenseNews. 07 Jun 2010

[ix] Rettman, Andrew. “France better off alone in Mali.”EUobserver. 25 Jan 2013

[x] ibid.

[xi] ibid.

[xii] Heisbourg, François. “A Surprising Little War.” Survival: Global Politics and Strategy. 55.April-May (2013)

[xiii] Barnett, Thomas, dir. Let’s rethink America’s military strategy. TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design), 2005.

[xiv] ibid.